A firm believer in the equality of all people, the great orator practiced what he preached.

The year 2020 will be remembered as a perfect storm of traumas. A global pandemic crashed on every shore. Politics rattled America. And a long-overdue racial reckoning began.

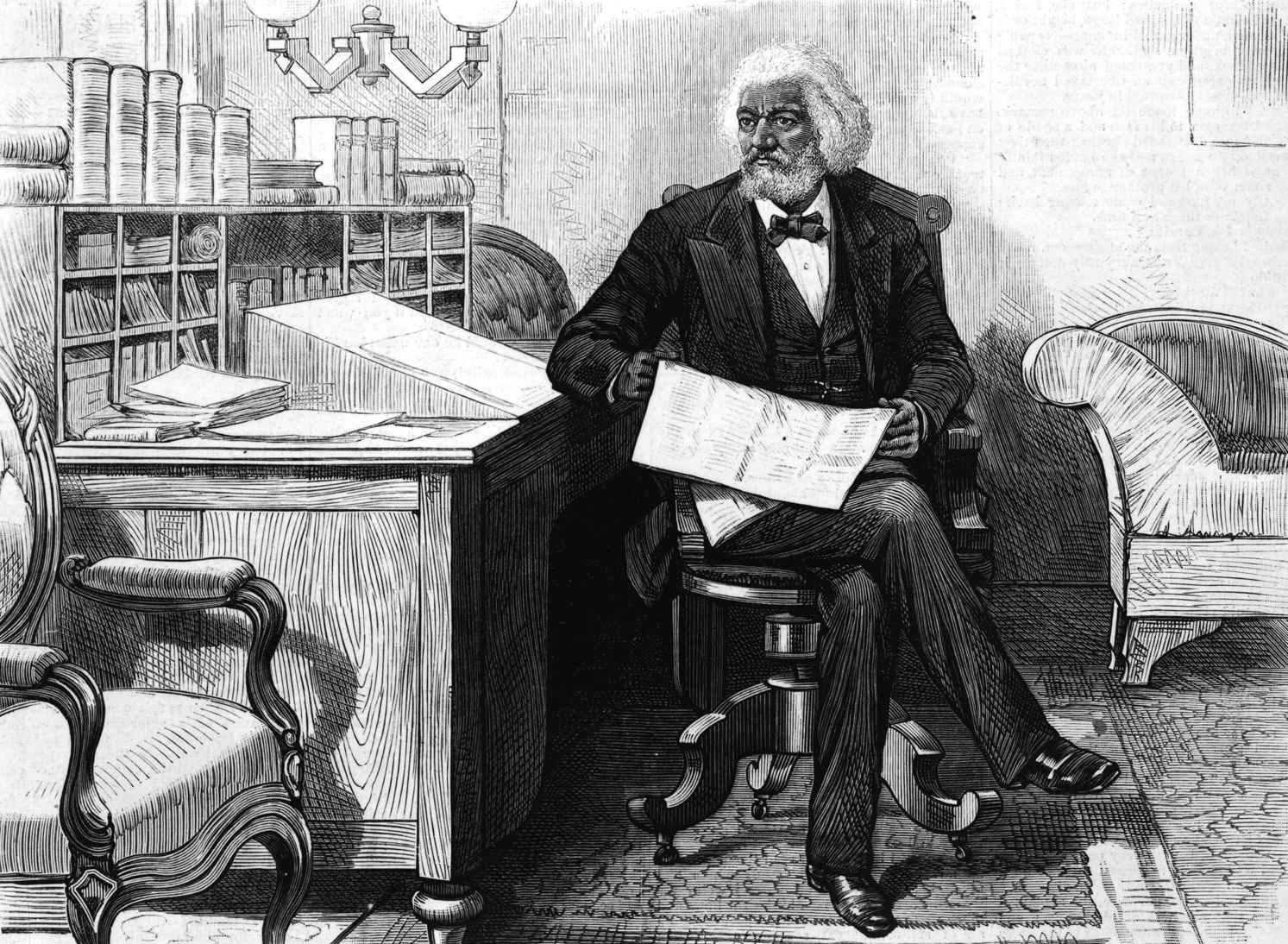

In the midst of this tumult, one name has emerged again and again—a man, it seems, destined to inform both his time and ours. Frederick Douglass once faced a reckoning of his own, and his words and deeds still teach us today.

Before becoming one of America’s great abolitionists, writers, orators, and icons, Frederick Douglass spent the first 20 years of his life in bondage. Born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, in February 1818, he was enslaved by multiple people during his first two decades. But none affected him like Captain Thomas Auld.

The son of an American Army commander during the War of 1812, Auld became a prominent local shipbuilder and pious Christian. He inherited enslaved people through his first wife, Lucretia, and quickly adapted to the ways of slavery, becoming a cruel master.

In one of three autobiographies Douglass wrote, he recalls his time on the Auld plantation as “the scene of some of my saddest experiences of slave life.” He wrote that Auld “subjected me to his will, made property of my body and soul, reduced me to a chattel, hired me out to a noted slave breaker to be worked like a beast and flogged into submission. …”

In 1838, after being passed around the Auld family and ending up back with the cruel captain, Douglass escaped the bonds of slavery disguised as a sailor and armed with false papers and a train ticket to the free North. (Explore the Underground Railroad’s ‘great central depot’ in New York.)

For the next 40-plus years, Auld remained a distant spectator as Douglass became one of the most famous and influential figures of his generation. Through mutual acquaintances, Auld was aware of Douglass’s best-selling books, read the many tributes to Douglass in newspaper after newspaper, and heard of the venues packed with people yearning to hear the master orator. Perhaps he even learned how much President Lincoln depended on Douglass’s insights and friendship.

Douglass and his former enslaver didn’t come face to face again until 1877, when Auld was 81. Sick and palsied, Auld knew he didn’t have much time left to make peace with his past. He sent his servant to invite the famous statesman to return to Auld’s home on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay once more.

Douglass accepted the invitation right away. The moment he arrived at Auld’s home was “the first time that a black man had ever entered a white home in St. Michaels by the front door, as an honored guest,” notes historian Dickson Preston, author of Young Frederick Douglass.

Douglass describes the encounter at length in his final autobiography. He remembers “holding [Auld’s] hand” and engaging in “friendly conversation.” When Auld addressed him as “Marshal Douglass” (Douglass was then serving as U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia), he corrected him, saying, “not Marshal, but Frederick to you, as formerly.” Those words caused Auld to “shed tears” and show “deep emotion.” For his part, Douglass writes that “seeing the circumstances of his condition affected me deeply, and for a time choked my voice and made me speechless.”

Near the end of the emotional meeting, Douglass asked Auld what he thought about his running away four decades before. “Frederick,” Auld responded, “I always knew you were too smart to be a slave. Had I been in your place I should have done as you did.” Touched by the answer, Douglass replied, “I did not run away from you, but from slavery.”

Such a warm exchange between two men with their history may be difficult to imagine from a 21st-century perspective. As was frequently the case with Douglass, however, there’s more to the encounter than meets the eye.

“Douglass shows us in this meeting that it is possible to carry oneself with dignity and to obey the dictates of justice, while still showing respect and kindness towards even those who have committed injustice toward you,” says Timothy Sandefur, a Douglass biographer and an adjunct scholar with the Cato Institute, a libertarian research institute in Washington, D.C.

But showing respect and kindness and forgetting past transgressions aren’t the same thing. “Any interpretation of this encounter that says Black people need to suck it up and forgive white people in order to have peace misses the mark completely,” says Noelle Trent, Director for Collections and Education at the National Civil Rights Museum. “This is not a lesson in forgiveness. This is a lesson in personal reconciliation.”

Part of that reconciliation came for Douglass by recognizing how far he’d come in his time away from Auld.

“This meeting was, in a way, a victory lap for Douglass,” says Ka’mal McClarin, a historian with the National Parks Service. “Douglass wanted to show Auld who he became after he was free of the constraints of slavery. The rest of the world had gotten to know the elder statesman, the Victorian gentleman, the United States Marshal; this was the moment when the man who ran away and the man who returned finally came full circle.”

One thing Douglass may have hoped to gain from reuniting with Auld was insight into his own family roots.

“Douglass never learned who his father really was,” says David Blight, professor of history at Yale University and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. “He was seeking knowledge of his paternity, and sought to know who his kinfolk were.”

Douglass also wanted to address how he had publicly denigrated Auld over the years. “He had made Thomas Auld a famous American villain,” says John Stauffer, a Douglass scholar and professor at Harvard University.

Indeed, in his final autobiography, Douglass acknowledges that “I had traveled through the length and breadth of this country and of England [to] hold up this conduct of his…to make his name and his deeds familiar to the world in four different languages.”

Though Douglass never expressed regret for telling the world what Auld had done, he did say he never wished “to do him injustice” and “entertain[ed] no malice” towards Auld.

“This meeting teaches a powerful lesson on rapprochement,” says Stauffer, the Harvard professor. “Douglass lived by a creed that in God’s eyes, all humans are equal. Douglass was once small and Auld great; now Douglass [was] great and Auld small. As such, Douglass treating Auld as his equal further reflects Douglass’s emphasis on equality: on treating all people as equals, with respect.”

In describing the encounter in his autobiography, Douglass says as much himself: “Here we were…in a sort of final settlement of past differences, preparatory to [Auld’s] stepping into his grave, where all distinctions are at an end, and where the great and the small, the slave and his master, are reduced to the same level.”

_