The most important environmental policies advanced since the last Earth Day.

By Umair Irfan and Rebecca Leber

Earth Day is here again on April 22, and since the last time our planet reached this part of its orbit, humanity has actually taken surprisingly big new steps to avert the gargantuan threats to life as we know it: toxic pollution, habitat destruction, extinction, and climate change.

These problems stem from the things we build, buy, and eat. But that also means if we change our actions, we can solve them.

Certainly, individual decisions about housing, appliances, transportation, and diet play a key role in reducing our harmful impacts on the planet. However, the biggest way you or I can have an impact is to pressure decision-makers at every level — city councils, statehouses, national governments, corporate boards — to cut greenhouse gas emissions, to protect wildlife beneath the sea, and to invest in cleaner energy. That means the most powerful tool to fix our environmental problems is ink on paper (or rather, pixels on screens).

Over the past year, this advocacy strategy blossomed. We now have the largest international land and ocean conservation target ever, a treaty to protect the high seas, and a commitment to phase out the most potent greenhouse gases completely.

In the US, the world’s largest historical emitter and second-largest current emitter of carbon dioxide, the government is putting more money than ever into solving climate change. It’s proposing tough new goalposts to draw down emissions from vehicles ranging from tiny hatchbacks to heavy-duty trucks, in an effort to step on the accelerator for EVs.

These were hard-fought wins, built on years of organizing, negotiations, and research. But these initiatives are just starting points, and they’re not enough to halt rising temperatures and the rapid pace of extinction.

Over the past year, we learned that the world is very likely to heat up past the 2.7 degree Fahrenheit (1.5 degree Celsius) goalpost of the Paris climate agreement, and scientists renewed their warnings that the window to act is slamming shut. Despite this, countries like the US are simultaneously working against their own climate commitments by authorizing more fossil fuel development that will further contribute to warming.

So turning ink on paper into an actual reduction in carbon dioxide pollution demands even more political pressure, ensuring that powerful institutions meet their benchmarks and holding them accountable if they don’t.

Here are the seven biggest policy wins for the planet since the last Earth Day:

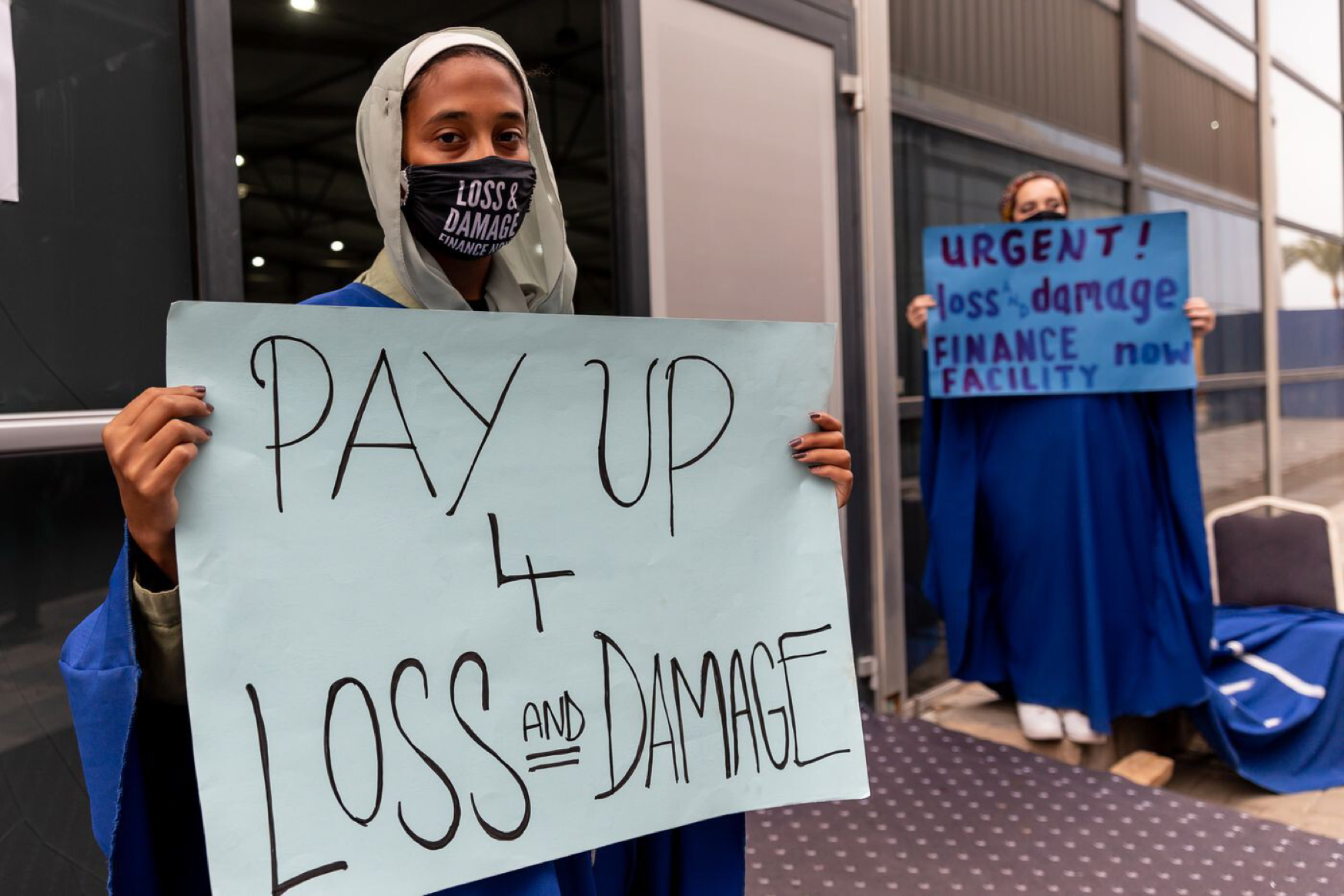

1) Rich countries are finally starting to show the money

The countries that contributed the most to climate change — again, the US is number one among them — also have the wealth to cope with many of its effects. The poorer countries that contributed the least, like Pakistan, Somalia, and the Marshall Islands, are already seeing some of the worst climate change impacts now: worsened drought, torrential rainfall, and sea level rise.

These countries argue that they deserve compensation for the damage from problems they didn’t cause and want financial help to deal with the shifts that lie ahead. But wealthy nations have been resistant to committing any money and were loath to sign on to any program that hinted at climate liability.

Over the past year, that edifice started to crumble. At the COP27 climate negotiations in Egypt last year, countries finally struck a deal to compensate poorer countries for ongoing climate destruction. The proposal is short on details, but the fact that a deal was reached at all is a huge step forward. It helps some of the most afflicted regions deal with climate change now, and by attaching a price tag to climate damages, the whole world has a stronger incentive to do more to keep warming in check.

Wealthy countries also struck direct climate deals with individual countries in the past year. The biggest was a $20 billion financing package from the US, Japan, and European countries to help Indonesia get off of coal. They also struck a similar $15.5 billion deal with Vietnam. Deals are in the works for India and Senegal, and more may be in the pipeline.

And just this week, the White House announced that the US would contribute $1 billion to the UN Green Climate Fund, which finances adaptation and mitigation efforts in developing countries.

2) An actual bipartisan climate treaty passed the Senate

With the narrow, bitter political divide in Congress, it’s been difficult to get anything done at all. But last year, 21 Republicans in the Senate voted with Democrats to pass the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

The treaty phases out a class of chemicals called hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). They’re used in refrigerators and air conditioners, but when they leak, they’re thousands of times more powerful than carbon dioxide at heating up the planet. Conversely, reducing a small amount of HFC pollution yields huge dividends. The Kigali Amendment alone is poised to avert upward of 1 degree Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius) of warming by the end of the century.

3) A new accord will preserve nearly one-third of the Earth

Countries also gathered last year to put together a treaty to protect biodiversity. At the COP15 meeting in Montreal, just about every country in the world agreed to work together to protect species from extinction and halt the decline of the lands, skies, and waters where they live.

The agreement, known as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, sets 23 targets that countries must achieve by 2030. Among them, countries have to stop subsidizing activities that continue to destroy wilderness, like mining and industrial fishing. The agreement also protects at least 30 percent of all land and water on Earth by 2030 — the largest land and ocean conservation commitment in history. There’s money behind it, too: Wealthy countries promised $30 billion for these efforts, roughly triple the amount spent currently.

4) The planet’s largest habitat has a new legal shield

Until recently, the open ocean was a bit of a black hole, legally speaking. Two hundred nautical miles off a country’s shoreline, no country has jurisdiction. This area adds up to half the surface area of the planet. It’s home to the largest animals and the tiniest creatures like phytoplankton, which provide about half of the oxygen we breathe.

Now, after 20 years of planning and negotiations, there’s a legal framework, backed by close to every country in the world, to protect this region. The treaty establishes protected areas in the ocean, akin to national parks, where fishing, mining, and dumping is prohibited. These regions will expand over time and will count toward the aforementioned targets in the Global Biodiversity Framework. The UN still has to adopt the agreement, though, and countries still have to ratify. And the tricky question of how to enforce it on the open seas remains.

5) Russia’s invasion of Ukraine accelerated Europe’s shift off of fossil fuels

Russia is the largest natural gas exporter in the world, and after Russia invaded Ukraine last year, many of its largest customers in Europe were desperate to find an alternative. Coal ended up filling some of the gap, but the energy crisis following the invasion also forced the continent to reckon with its entire relationship with fossil fuels.

Spikes in oil and gas prices alongside overall cost declines in wind and solar convinced policymakers to harness more clean energy. “After the invasion, energy security emerged as additional strong motivation to accelerate renewable energy deployment,” said the International Energy Agency. Individuals are also using drawing on renewables to insulate themselves from volatility in energy markets. In 2022, European households installed three times as many gigawatts of solar as they did in 2021. That’s on track to triple again in the next four years.

6) The US finally has a law to deal with climate change

Last summer, President Joe Biden and congressional Democrats passed an enormous spending influx to move the US economy away from fossil fuels. The law, known as the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, includes $369 billion for an array of climate priorities. Consumers will see tax breaks and rebates aimed at electrifying their homes and cars, utilities will receive investments to make the transition off of coal, oil and gas polluters will be held to new fees for their methane pollution, and communities that have been harmed by redlining policies and environmental racism will receive grants to clean up local pollution.

The law will ultimately be an important marker in propelling the US into a future with more electric transportation, electric homes, and creating a homegrown clean energy. But the IRA is early yet in its implementation at the federal, state, and local level.

If that rollout goes well, the US could finally meet the Biden administration’s aim of slashing greenhouse gas pollution in half compared to 2005 levels by the end of the decade. The US is already one-third of the way there, and the IRA provides the extra boost, while helping to clean up the everyday air and water pollution Americans must contend with. But, worryingly, US emissions are now trending upward.

7) Fossil fuel-powered cars will soon be parked

Transportation is the largest source of climate pollution in the US, and one of the largest in the world. Switching cars and trucks from gasoline and diesel to fuel cells and batteries is thus an essential step for meeting climate change goals. Electric vehicles also avoid dangerous pollutants like particulates and nitrogen oxides. But EVs only made up 5.8 percent of cars sold in the US last year and just over 10 percent around the world.

To speed up this trend, California last year approved a finish line for fossil fuel-powered vehicles by 2035. Other states like New York and Massachusetts have since joined the race. More recently, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed a new set of pollution regulations for cars, pickups, SUVs, and delivery trucks. The rules mean that by 2032, two-thirds of cars sold in the US will have to run on electrons.

The European Union also proposed a ban on gasoline and diesel vehicles by 2035. With looming cutoffs in the largest car markets in the world, the global auto industry is getting a loud signal that the internal combustion engine’s days are numbered.