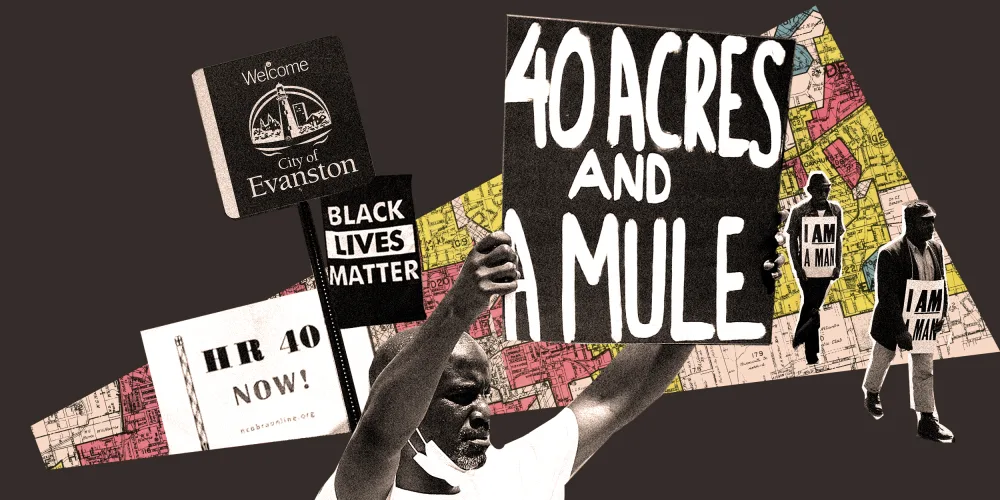

Black Americans have been fighting for reparations tied to slavery for generations. Here’s what that fight looks like in 2021.

After decades of work from activists pushing the issue, presidential candidates, Congress members, local governments and private institutions have debated whether and how the federal government should issue reparations for Black Americans who are descendants of slaves.

As the Biden administration promises to confront structural racism and inequality, a growing number of Democratic lawmakers have given their support to H.R. 40, a decades-old bill first introduced by Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., in 1989. The bill would create a commission to study slavery and discrimination in the United States and potential reparations proposals for restitution.

In April, H.R. 40 moved out of committee for the first time, potentially setting up a floor vote on the legislation.

Meanwhile, the ongoing reckoning with racial injustice and the health disparities exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic have called further attention to the ways Black people have faced generations of systemic discrimination.

But with an issue so large and complex, proponents suggest a range of ways the U.S. could engage in reparations while opponents say the time for redress for slavery and the discrimination that followed has passed.

Demands for reparations have endured for more than a century

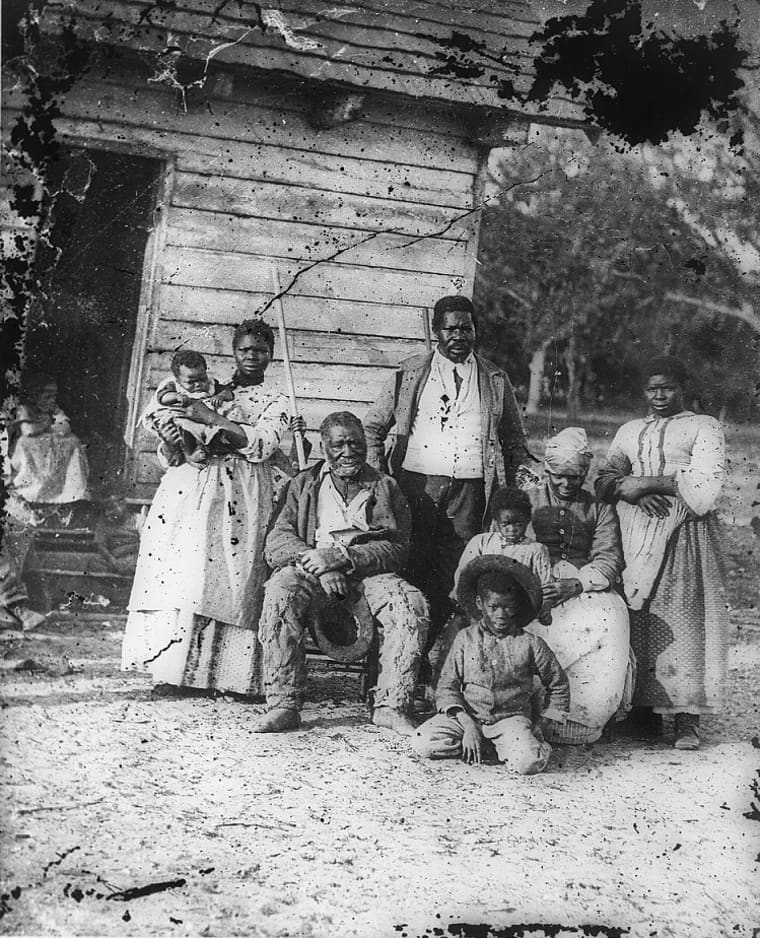

Calls for reparations for enslaved men and women — and later, their descendants — have been made in various forms since the end of the Civil War. But these demands have never been met by the federal government.

In 1865, Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman ordered that land confiscated from Confederate landowners be divided up into 40-acre portions and distributed to newly emancipated Black families. Following President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, however, the order granting “40 acres and a mule” was swiftly rescinded by new President Andrew Johnson. The majority of the land was returned to white landowners.

After the Civil War, formerly enslaved men and women also argued that their unpaid labor while in bondage entitled them to pensions. Their demands received resistance from the federal government, which accused prominent pension supporters of fraud and ignored pension bills brought up in Congress.

But as the federal government denied land and resources to formerly enslaved people, it created new pathways for land ownership for white Americans. For instance, the federal government passed the Homestead Act in 1862, granting 160-acre plots to applicants.

“Black families received no assets from the federal government while large numbers of white families received substantial assets as a starting point for building wealth in the United States” under the act, said William Darity, a professor of public policy at Duke University. Darity recently co-authored a book on reparations with folklorist Kirsten Mullen titled “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century.”

Darity added that calls for reparations are a “specific claim that is connected to the failure to provide the ancestors of today’s living descendants who were deprived of the 40-acre land grants that they were promised.”

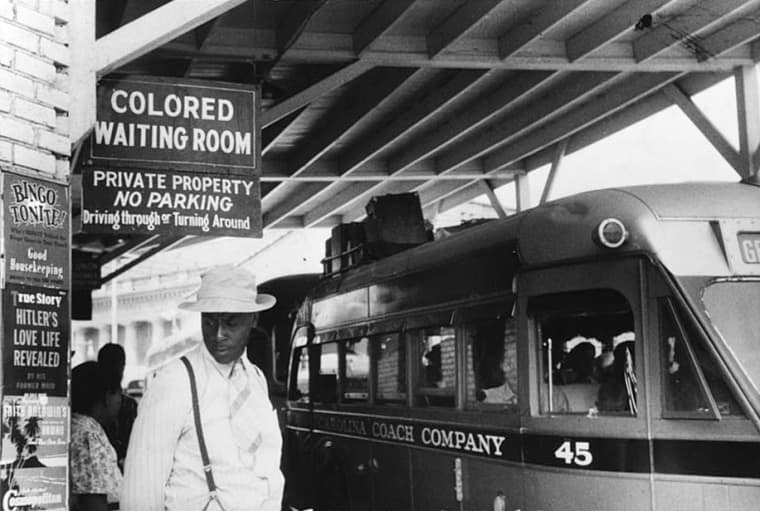

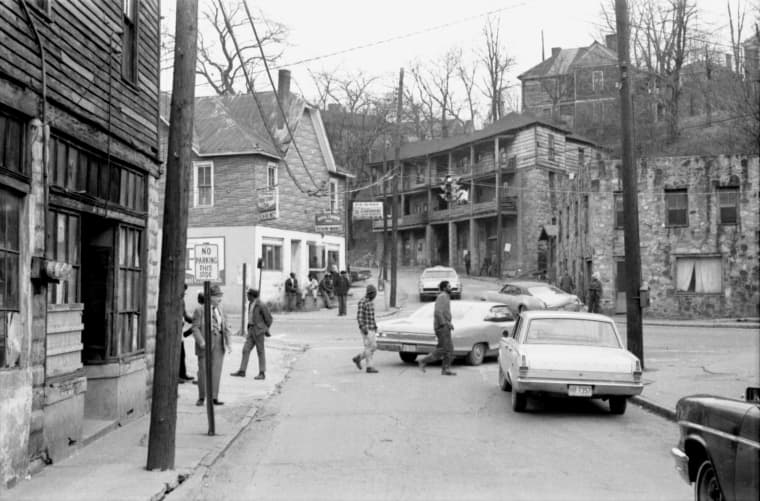

After the war and during the Reconstruction era, Black Southerners made political, social and economic progress, but these gains were quickly overturned. Discrimination was further entrenched through laws regulating every facet of Black life, including housing restrictions, legal segregation and racially motivated terrorism and lynchings.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Black Americans also continued to be denied opportunities to build wealth under federal programs that benefited white families and communities.

Under the GI Bill, for example, “mortgage and school tuition benefits extended to black soldiers were devalued due to state endorsed and enforced segregation,” law professor Adrienne Davis argued in a pro-reparations human rights brief published in 2000.

“There were far fewer places they could attend school or purchase housing,” Davis wrote. “The schools they were able to attend and houses they were able to buy were less valuable because they were black institutions and neighborhoods, respectively, in an economy that valued whiteness.”

Excluding domestic and farm workers from Social Security legislation effectively shut out 60 percent of Black people “across the U.S. and 75 percent in southern states who worked in these occupations,” according to policy think tank the Brookings Institution.

Experts argue that such omissions from federal policy have not been fully corrected and have been magnified by widening health, education, employment and housing disparities, as well as a lack of access to capital.

Collectively, these historical and current disadvantages have led reparations proponents to argue that while slavery is where denials of wealth and equal rights began, the cumulative effects of both slavery and systematic federal denials of opportunity that followed continue to impact the descendants of enslaved people in the present.

Experts disagree on what reparations should look like

In recent years, reparations have often been discussed alongside the racial wealth gap, or the difference between wealth held by white Americans compared to that of other races.

Research has found that the gap between white and Black Americans has not narrowed in recent decades. White households hold roughly 10 times more wealth than Black ones, similar to the gap in 1968. While Black Americans account for roughly 13 percent of the American population, they hold about 4 percent of America’s wealth. Experts note the gap is not due to a lack of education or effort but rather is due to a lack of capital and resources that have left Black individuals more vulnerable to economic shocks and made it difficult for Black families to build inheritable wealth over generations.

Darity and Mullen say closing this wealth gap should be a fundamental goal of a reparations program and should guide how such a program is structured. In their book, Darity and Mullen call for a system of reparations that primarily consists of direct financial payments made by the federal government to eligible Black Americans who had at least one ancestor enslaved in the United States.

Proposals for reparations programs have also been raised by reparations advocacy groups in recent decades. The National African American Reparations Commission, for example, has a10-point reparations plan that includes calls for a national apology for slavery and subsequent discrimination; a repatriation program that would allow interested people to receive assistance when exercising their “right to return” to an African nation of their choice; affordable housing and education programs; and the preservation of Black monuments and sacred sites, with the proposals benefiting any person of African descent living in the US.

Other proposals, like one proposed by Andre Perry and Rashawn Ray for the Brookings Institution, would also specifically provide restitution to descendants with at least one ancestor enslaved in the U.S., coupling direct financial payment with plans for free college tuition, student loan forgiveness, grants for down payments and housing revitalization and grants for Black-owned businesses.

“Making the American Dream an equitable reality demands the same U.S. government that denied wealth to Blacks restore that deferred wealth through reparations to their descendants,” they wrote last year.

The variety of proposals show that even among supporters of reparations, there is some disagreement about what a full program should look like and what exactly should be described as “true reparations.”

“I think we would be doing ourselves a huge disservice if we were just talking about financial compensation alone,” said Dreisen Heath, a racial justice researcher with Human Rights Watch.

While Heath said she did support and see the value in direct financial payments, she added that money alone “is not going to fix if you were wrongly convicted in a racist legal system. That’s not going to fix your access to preventative health care. All of these other harms are connected to the racial wealth gap but are not exclusively defined by or can be relieved by financial compensation.”

Some local governments — most notably Evanston, Illinois, and Asheville, North Carolina — are also attempting to issue reparations for historical discrimination Black residents of these areas faced. These attempts have been praised by some proponents, who say the wide-ranging harms of slavery and subsequent discrimination requires a multipronged solution.

“Reparations efforts at multiple levels are necessary because the harms were on multiple levels — the institutional, at the state level and at the federal level,” Heath said. “Specific harms were committed and need to be remedied in a very specific way. There’s no blanket reparations program for a specific community.”

Still, critics of such programs, like Darity and Mullen, say municipal efforts are not significant enough in scale because of sheer municipal budget restrictions. They also say localized programs simply miss the point.

“We are seeing racial equity initiatives that are being touted as reparations programs,” Mullen said. “For us, a reparations program must center on eliminating the racial wealth gap, and putting people on committees and panels is not going to do that.”

H.R. 40 has also sparked debate among reparations proponents

Discussion of how to best conceptualize reparations has spilled over into debates over H.R. 40, which languished in a House subcommittee for more than three decades before being voted out of committee this year. While supporters of the legislation argue it is the best vehicle for better understanding the need for and possible avenues of providing reparations, Darity and Mullen say in its current form, the measure could ultimately do more harm than good.

“One of the problems with H.R. 40 is that it is not at all clear that it provides us with a direction towards eliminating the racial wealth gap,” Darity said. He added that the bill’s impacts are limited because it creates a commission rather than directly approving a reparations program.

Supporters of the bill, including members of pro-reparations advocacy groups like the National African American Reparations Commission and the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America counter that the bill would do more than simply study the evidence supporting reparations and is a crucial step toward providing reparative justice.

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, the bill’s main sponsor, and other congressional Democratic leaders have said they hope to move forward with a House floor vote on the bill this summer.

Still, reaction to the legislation not only reveals fundamental differences between reparations proponents but also shows there continues to be a vocal contingent of reparations critics who argue that a federal effort to provide redress for the harms of slavery and the decades of discrimination that followed is unnecessary. Critics say slavery happened too long ago and thus the harms are too old to be repaired. Others say the mere idea of reparations frames Black Americans as helpless.

“Reparation is divisive. It speaks to the fact that we are a hapless, hopeless race that never did anything but wait for white people to show up and help us — and it’s a falsehood,” Utah Rep. Burgess Owens, one of two Black Republicans in the House, said during debate on H.R. 40 in April. “It’s demeaning to my parents’ generation.”

Experts argue the focus shouldn’t be on whether reparations are divisive but if they are necessary, saying Black American descendants of enslaved people have a valid claim for redress and restitution.

“There hasn’t been this amount of stalling for reparations for Japanese Americans, or around the appropriation for restitution for 9/11 victims, or continued support for Holocaust survivors in the U.S.,” Heath said. “Reparation is only seen as a bad word when we’re talking about repair and restitution for Black people.”

Ultimately, supporters argue the need for reparations should not be judged based on how popular the issue is publicly but instead should be looked at as a necessary correction for the moral, political and economic failures that have been created by federal policy at the expense of Black Americans.

Darity argued that even if detailed reparations measures are not politically feasible in Congress now, it is important that “the footprints must be put in place” for future efforts.

“If you think about the generational relationship to enslavement, you find that it doesn’t really feel all that long ago,” Darity said of efforts to frame reparations as solely focused on the past. “But what’s more important is that the effects of the period of enslavement are still felt and still embodied in the kinds of consequences for Black lives today.”