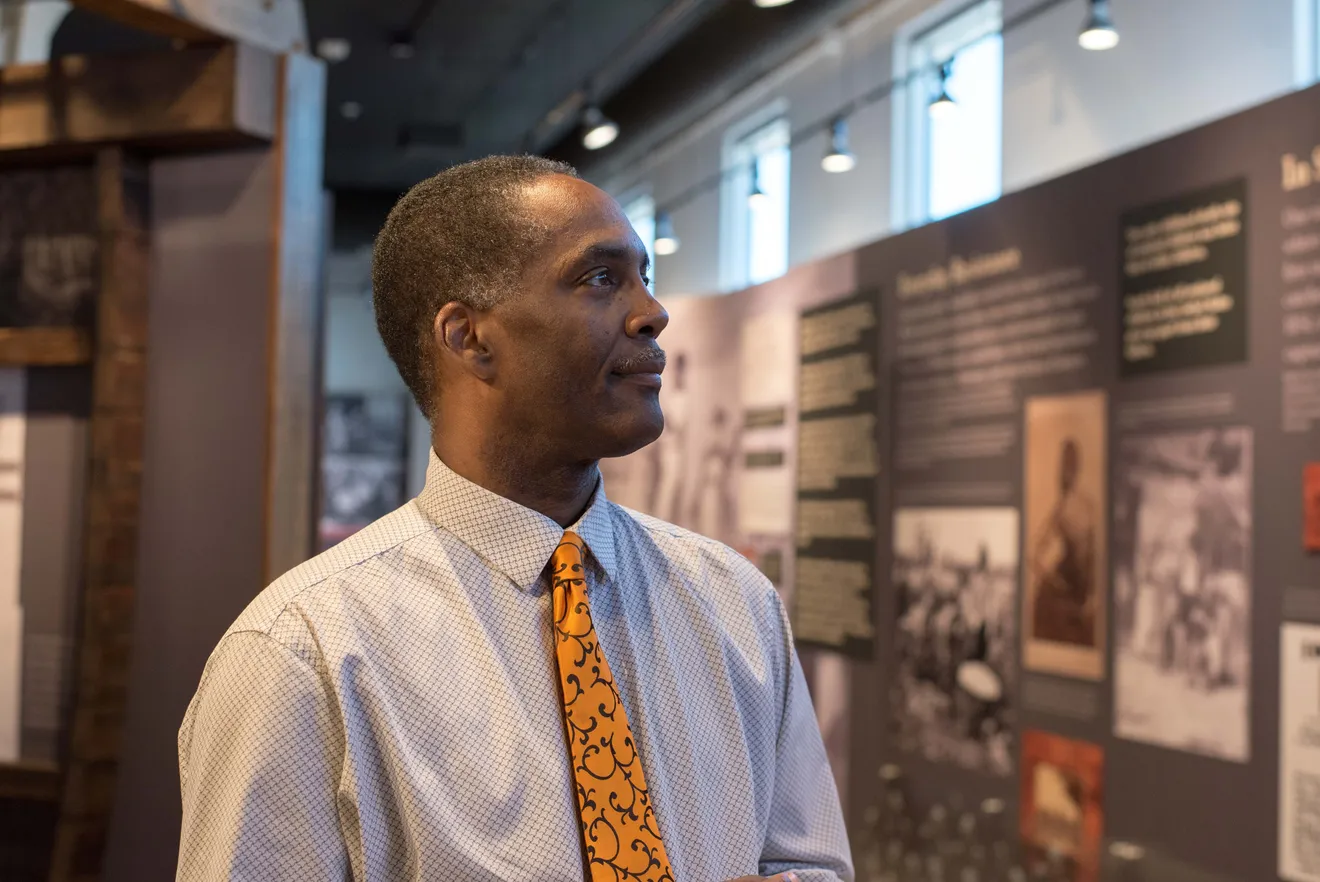

Reggie Jackson, a writer for the Milwaukee Independent and the former head griot, or oral historian, at America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee, has a long history of military service in his family stretching back to the Civil War.

But when two of his uncles who served in World War II returned to their home state of Mississippi, they found that being a veteran wasn’t enough to reap the benefits of the GI Bill, which had passed in 1944.

This is because Jackson’s uncles were Black.

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act provided veterans with financial aid to reduce the possibility of an economic depression after World War II. But Jackson said two components of the GI Bill — free college tuition and home loans under the Veterans Administration Guarantee Home Loan Program — were not available to his uncles at the time.

“It just didn’t work out that way, because the federal government allowed the states to control the allocation of both programs,” Jackson said. “It’s just unfortunate.”

A national debt: Should the government compensate for slavery and racism?

Molly Carmichael and Martha DanielsWisconsin WatchView Comments0:001:01ADhttps://imasdk.googleapis.com/js/core/bridge3.480.1_en.html#goog_388352877

Reggie Jackson, a writer for the Milwaukee Independent and the former head griot, or oral historian, at America’s Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee, has a long history of military service in his family stretching back to the Civil War.

But when two of his uncles who served in World War II returned to their home state of Mississippi, they found that being a veteran wasn’t enough to reap the benefits of the GI Bill, which had passed in 1944.

This is because Jackson’s uncles were Black.

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act provided veterans with financial aid to reduce the possibility of an economic depression after World War II. But Jackson said two components of the GI Bill — free college tuition and home loans under the Veterans Administration Guarantee Home Loan Program — were not available to his uncles at the time.

“It just didn’t work out that way, because the federal government allowed the states to control the allocation of both programs,” Jackson said. “It’s just unfortunate.”https://ece1c731ab2f3f5faf70894e8e13bec7.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

In many southern states like Mississippi, Black soldiers were denied access to these wealth-building programs. And when it came to college, many were denied the opportunity to attend southern state schools because of segregation.

Jackson said those two uncles never went to college. When they bought houses, they did so without government help.

These barriers continue to take a toll on the wealth of Black Americans, who own and earn just a fraction of their white counterparts.

Today, there are increasing calls for government reparations — especially among Black Americans — for the up to 40 million U.S. residents whose ancestors endured generations of state-sanctioned slavery, and for the legal and de facto discrimination that continued after that repugnant institution officially ended in 1865.

Evanston, Illinois, recently enacted a reparations program that gives $25,000 in housing assistance to certain African-American residents or their descendants harmed by discriminatory housing policies abolished in 1969.

The racial wealth gap began with slavery, but even after the institution was abolished, the gap persisted, said University of Wisconsin-Madison history professor Steve Kantrowitz.

Many Black Americans could not qualify for Social Security, as jobs typically held by Black workers, such as agricultural and domestic positions, were excluded from the program. Black residents also were blocked from getting some home loans and from living in the types of neighborhoods where home values were steady or rising. Such barriers made it nearly impossible for Black people to acquire and accumulate wealth at the rate of white Americans, Kantrowitz said.

“So the end of slavery didn’t mean that Black and white people were suddenly on an equal economic, political, civil footing,” Kantrowitz said. “It meant instead that the institution of slavery had been formally abolished, and disabilities that followed from slavery were supposed to be abolished.”

Jackson said this wasn’t just a hindrance for his uncles.

“What it ends up doing is it takes longer for you to be able to begin to build that generational wealth in your family,” Jackson said. “As a result, you lose years, and in some cases, well over a decade of being able to build equity by being a homeowner and the benefits of that — you can use that equity to send your children to college without them having debt and things of that nature.”

That idea of compensating for lost years of wealth is where reparations come into play.

Leading the way on reparations

There is no consensus on what reparations would look like — or whether such a program is even warranted or feasible. Would it be federal or local? Would it be a check with no strings? Or indirect, such as investing in schools and Black community programs? Should it go to all Black Americans or just those whose ancestors were enslaved? What would be done about the racial tensions and jealousies that such a program could spark?

Evanston — home of Northwestern University — approved a plan to use tax money from legal cannabis sales toward housing assistance for Black Evanston residents. The city chose a “restorative housing program” as their first initiative because of targeted acts of redlining, segregation and refusing loans to Black residents, which Evanston engaged in from 1919 to 1969.

Spearheaded by then-Ald. Robin Rue Simmons, the $400,000 program aims to increase Black homeownership and build intergenerational wealth. Qualified residents receive $25,000 toward buying or improving a home or mortgage assistance. Simmons left city government and now runs a nonprofit, FirstRepair, that encourages local reparations programs.

In an Aug. 10 Washington Post guest column, Simmons said 16 people have received compensation so far.

Meleika Gardner, Evanston resident and founder of Evanston Live TV, said the program has opened the country up to a conversation about reparations — something she never thought was possible for Black Americans while growing up. However, what Evanston is doing is not actually reparations, Gardner argued, but an affordable housing program, which she supports.

Gardner believes that the housing program alone should not be called reparations, and that Black residents should also be receiving cash payments.

“That’s like someone murdering your family, destroying your house, destroying your car, and then walking up to you, tossing you a quarter, and saying, ‘Well, here, this is a start,’ ” Gardner said.

Simmons agreed this is just a first step.

“But we all know the road to repair injustice in the Black community is going to be a generation of work,” Simmons said during the March 22 council meeting at which the program was approved. “It’s going to be many more initiatives, programs and more funding. What I am excited about is the new engagement, the new interest in what we’re doing.”

National conversation restarts

While Evanston is thought to be the first U.S. city to pass a reparations program, the conversation regarding reparations for Black Americans is not new.

In 1989, Democratic U.S. Rep. John Conyers Jr. of Michigan introduced HR 40, a bill to establish a reparations commission that would study the lasting effects of slavery, public and private discriminatory practices and “lingering negative effects” on present African-American residents.

In early 2021, Democratic Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas reintroduced HR 40, taking over as the bill’s sponsor from Conyers, who died in 2019. Lee explained during a 2019 hearing that one of the goals of a reparations process is to show Americans “the many kinds of injuries sustained from chattel slavery and its continuing vestiges.”

On April 14, the House Judiciary Committee voted to move forward with HR 40, which would establish a commission to study the effects of slavery and recommend “appropriate remedies” to the Congress. It concluded with a 25-17 first-ever vote on reparations in Congress. It is unclear when the bill would move to a full House vote.

The recent COVID-19 stimulus programs could serve as a template for how the United States could compensate the descendants of enslaved people, said William Darity Jr., a Duke University economics professor, and folklorist A. Kirsten Mullen, the authors of a pro-reparations book, “From Here to Equality,” during a recent webinar.

The type of plan advocated by Darity and Mullen would require the federal government to allocate about $800,000 to an eligible Black household, for a total cost upward of $10 trillion. Though this is a significant amount of money, the two argue that it is warranted given the drastic inequality that persists today, as Black families have an estimated one-tenth of the wealth on average as white families.

Milwaukee: Epicenter of inequality

That inequality is especially pronounced in Wisconsin’s largest city.

Milwaukee has among the worst gaps in standard of living between white and Black residents, according to a 2020 study by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Center for Economic Development.

On a variety of measures ranging from income and health to homeownership and educational attainment, Milwaukee is the fourth-worst major city for Black people in the nation, but the 18th best for white people, center director Marc Levine told Wisconsin Watch.

Ald. Khalif Rainey, who represents Milwaukee’s 7th District, said he believes something needs to be done. But he warned that anything akin to reparations would likely face stiff resistance in Milwaukee.

“This is one of the more racist cities in the country, one of the more segregated cities in the country, and definitely a community where African Americans are suffering more than other communities across the country,” Rainey said.

Passing a reparations program would be a political challenge, but the United States has done it before. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 gave residents of Japanese descent held in internment camps during World War II and their descendants $20,000 payments.

Views on reparations mixed

But the sheer cost of compensating African American residents damaged by hundreds of years of slavery and discrimination is sure to spark opposition.

From 2019 to 2020, the number of Black Americans supporting reparations increased from 65% to 84%, according to a survey by Democracy in Color, an organization focused on race and politics. Support among white Americans is rising but still far below half, the poll found. In 2019, 23% of white residents polled said they favored reparations, rising to 39% in 2020, the poll found.

Reparations also face a steep climb in Congress. Then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell flatly rejected the idea in 2019, saying, “I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea.”

But for Reggie Jackson, who can trace his ancestry back to 1792, reparations to individuals and Black communities would put right a longstanding wrong.

Said Jackson: “I say (to white people), ‘You’re not far ahead because of your Protestant work ethic or because you’re smarter and you make better decisions. You’re further ahead because the federal government is hooking you up time and time and time again, giving you access to these things that help to build generational wealth, and denying those same opportunities for Black people consistently, over a very, very, very long period of time.’ ”

This story was produced as part of an investigative reporting class at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication under the direction of Dee J. Hall, Wisconsin Watch’s managing editor. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication.