Defense attorneys removed 11 of the 12 Black potential jurors Wednesday, ensuring that the three white men accused of killing Ahmaud Arbery will face a nearly all-white jury in their trial.

Just one Black person will serve as a juror in the trial of three white men accused of killing Ahmaud Arbery, even after the judge overseeing the case said there appeared to be “intentional discrimination” in jury selection.

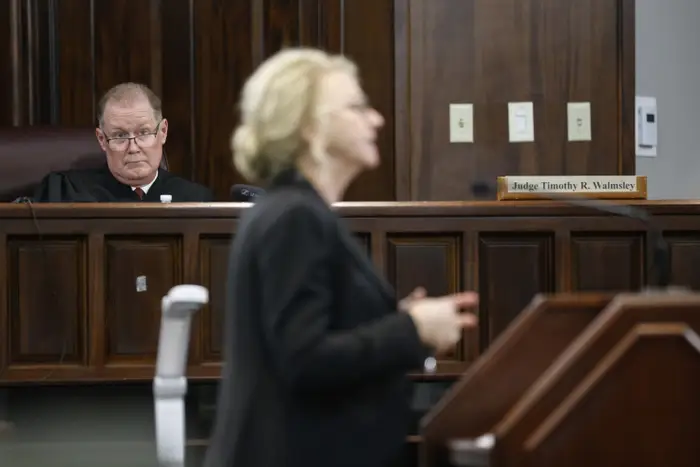

Attorneys for Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William Bryan Jr. on Wednesday removed 11 of the 12 Black panelists being considered for the jury, prompting prosecutors to ask Judge Timothy Walmsley to reseat eight of them. Prosecutors argued the Black panelists were removed from the jury pool simply because of their race. Walmsley declined to reseat them, citing state law, even as he acknowledged the racial overtones of the case.

“This court has found that there appears to be intentional discrimination on the panel,” the judge said, “but that doesn’t mean the court has the authority to reseat simply because we have this prima facie case.”

The move ensured that the three men accused of chasing down and fatally shooting Arbery on Feb. 23, 2020, as he was jogging in Brunswick, Georgia, will face an overwhelmingly white jury in their upcoming trial. His death, and the delay of local authorities in charging the three men, prompted widespread protests in 2020 after a video of the shooting was released.

Wednesday’s decision also means the three men will face a jury whose racial makeup will differ significantly from their community in Brunswick, where 26% of residents are Black.

In court on Wednesday, defense attorneys considered 48 possible jurors, 12 of whom were Black and 36 white. They were allowed to remove 24 of the panelists and used that power to remove 11 of the Black potential jurors.

To make her case that race was the main reason they were removed, prosecutor Linda Dunikoski said all the court needed was “to do the math.”

Despite agreeing with prosecutors on how those numbers appeared, Walmsley said the court was limited by Georgia law.

Since the defense attorneys presented other reasons for removing the potential jurors than race, the court could only take action if it found that the attorneys had not been “genuine,” he explained.

“At least in the state of Georgia, the court, if it hears a legitimate, nondiscriminatory, clear, and reasonably specific … reason related to the case — that is usually enough to get the court to a finding in this third phase where the panelist doesn’t need to be reseated,” Walmsley said.

If he had brought the Black panelists back into the jury pool, the judge would have had to find that defense attorneys were essentially lying in court.

“The court is not going to place into the defense a finding that they are … not being truthful to the court,” Walmsley said.

During Wednesday’s court hearing, defense attorneys provided numerous reasons why some of the Black potential jurors were cut from the jury pool. One panelist, attorney Bob Rubin said, had a fiancé who had expressed that she was a “strong supporter of the justice for Ahmaud movement” on her Facebook page.

That panelist, Rubin argued, had also said they had resigned from their job as a police officer when in fact their certification had been revoked.

Prosecutors pointed out most of the people interviewed for the jury pool had shown that they had developed opinions on the case because of the worldwide media attention it had received. Despite there being two other former law enforcement officers in the panel — both of whom are white — Dunikoski argued defense attorneys had only gone through the records of the Black former officer.

“They have not said that they have gone and pulled their records,” Dunikoski said.

Another Black panelist told attorneys during questioning that her understanding of the case was that a “young man was shot due to his color and the three men who committed the act almost got away.”

Dunikoski argued that all jurors had been asked what they knew of the facts of the case based on what they’d heard in media reports.

“We all know that’s what she said, but [the defense] failed to provide any reason that she’s different than any other juror, stating the facts they had heard from the news media and TV,” she said. “The real question here was: Can you put that aside? Because it’s been based on news media … and in this case this juror did indicate she could do that.”

Defense attorneys pointed out one Black panelist had a Black Lives Matter sticker on his car, but the man had said he’d bought the vehicle with the sticker already attached.

Defense attorney Kevin Gough questioned the man’s honesty.

“It seemed to me like he was distancing himself from his own political statements,” Gough said.

Other panelists were flagged by defense attorneys because they had participated in community events connected to Arbery’s death, including a “Run With Ahmaud” event.

Attorneys on both sides have struggled to construct a jury for the upcoming trial, delaying opening statements for several days already. It’s been difficult in the small tight-knit community to find impartial jurors who have not been affected by the killing; many people had relationships to the defendants and the victim.

Wednesday’s arguments were also one of the multiple ways that race has already played a central role in the trial. Prospective jurors have been questioned about their views on the Confederate flag, the Black Lives Matter movement, and how Black people are treated in the criminal justice system.

“In this particular case, there are significant overtones of race to begin with,” Walmsley said. “Because of that, it gets very difficult for the court.”