In first grade, my friend asked me who my real parents are. I was over for a play date, and we were sitting in a big comfy chair near the front window of her house. The question surprised me because no one had asked me that before. I said to her that the parents I have now are my real parents. I insisted that I prefer to use “birth parents” when referring to my biological parents, and added that my real parents are the ones who have raised and supported me.

I was 13 months old when my parents and brother flew to China to bring me home to the United States. Raised in a Jewish interracial family, my parents are Caucasian and my older brother, adopted earlier, is Cambodian. There was never a specific time I remember being told I was adopted. My parents never wanted, or needed, to hide the truth from me. For as long as I remember, I just always knew. They told me the day they held me for the first time. That day was the beginning of a different path: Being adopted didn’t give me a better life, but it changed the route of my journey.

Raising awareness for adoption

The lack of adoption awareness has a negative impact on adoptees like me.

November is recognized as National Adoption Month, and it is time the general public makes a serious effort to change the way they view and talk about adoption. People are not properly educated on adoption because it isn’t generally included in school curriculums, and some content unintentionally triggers negative emotions for adoptees. Each adoptee’s experience is different. People don’t know about the depths of adoption unless they have been personally impacted by it, or were adopted themselves.

For the kids: Three ways the foster care system can emerge stronger after the coronavirus pandemic

Over the past several years, I’ve had multiple experiences with school assignments that are not inclusive and have negatively affected me. For instance, I was told to complete a Punnett Square project my freshman year of high school, which measures the probability of inheriting physical characteristics from each (biological) parent.

After the project was explained, I reluctantly walked up to my teacher to ask how I could complete the assignment when I don’t know my biological history. When my teacher replied to make up the traits of my birth parents, frustration washed over me, because that teacher saw it as an easy solution for me to complete my work. But I felt dismissed, as if the assignment was more important than the truth of my upbringing.

Establishing awareness on adoption isn’t just knowing what it is and that it exists. Although it’s a good place to start, there is so much more to the experiences adoptees go through. Adoption should be discussed in family life education and biology classes. Further trauma to adoptees could be prevented if schools take adoption education more seriously. Family tree and inheritance projects need to either be removed or altered to reflect different types of families.

Parents spoke up, feds stepped in: Parents stood up for their children. Then the Biden administration targeted them.

Currently, these projects don’t accurately represent the population as a whole, and they spread a message that families are only formed one way. This unintentionally singles out adoptees, which can have detrimental effects.

The trauma affecting adopted children

Many adoptees live with trauma, whether pre-verbal or conscious memories.

There’s a common misconception that adoptees are “lucky” to have been adopted, but people don’t take into consideration that every adoptee lives with separation trauma. My battle with mental health challenges began when I was 13 years old. My world began to shatter; I wasn’t sure where I belonged. I started questioning my identity and struggled with depression and anxiety, which resulted in the secrecy of my self-harming and suicidal thoughts. I was in denial that being left by my birth parents as an infant was traumatic, although I didn’t realize it at the time.

Standing up for life: Why America’s quest for equality should include unborn children

During my third year in therapy, I started to uncover the triggers behind how I was feeling. I learned that there are seven core “issues” an adoptee goes through: loss, rejection, guilt and shame, grief, identity, intimacy and mastery/control. Once I began to accept that I had to process these emotions, I was able to connect the trauma from being left by my birth mother to my mental health struggles. Identifying my triggers helped me tremendously in my journey.

There are difficulties adoptees face daily that most people wouldn’t even stop to think about. While this month honors and recognizes the lives changed by adoption, it should ignite a serious, prolonged effort to talk about adoption in schools and our communities.

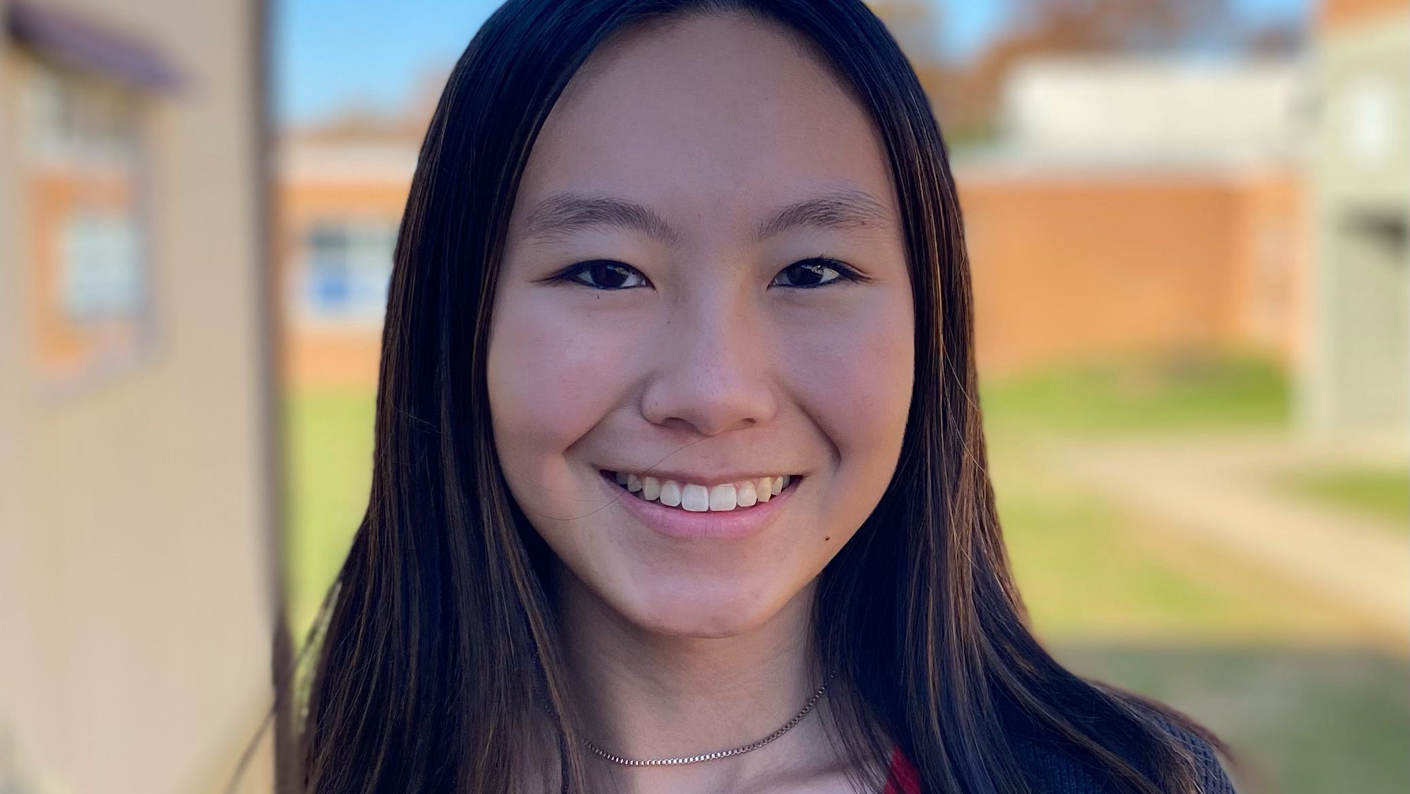

Jada Bromberg, a high school senior in Fairfax, Virginia, is active in adoption and mental health organizations.