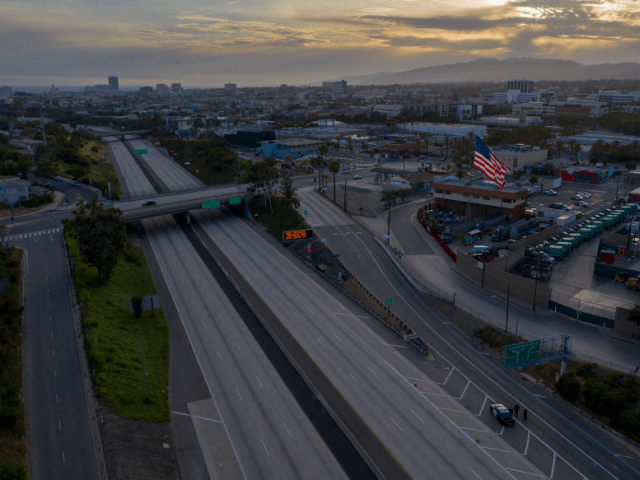

The California city of Santa Monica is offering housing to black families that owned homes in the path of Interstate 10 and other urban renewal projects built in the 1950s.

Beginning in January, those former residents and their descendants will receive “priority access to apartments with below-market rents in the hopes that they’ll come back to the coastal city in Los Angeles County.”

Nichelle Monroe, who said in a Sacramento Bee article that her grandparents were forced out of the Pico neighborhood, said she doesn’t think the program goes far enough. She wants help buying a home of her choice.

“But what else is there?” Monroe said. “The theft is still there. The generational wealth is still gone.”

The Bee reported on the history of “racist harms related to housing and property” in California infrastructure projects:

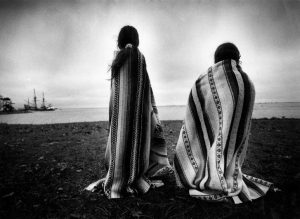

Santa Monica’s act of civic penance is an attempt to recognize the harm done to largely black communities during the post-World War II era of freeway building and urban renewal, the [Los Angeles] Times said. The program is part of a nationwide movement to compensate residents for racist harms related to housing and property. In September, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law that authorized the return of shorefront land known as Bruce’s Beach to the descendants of a black couple who were run out of Manhattan Beach nearly a century ago.

Affordable housing will also be available for families removed when they city bulldozed another Black area, Belmar Triangle, to build the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. Children and grandchildren of those who were displaced will be eligible. Some 600 families lost their homes when Interstate 10 was built through the Pico neighborhood, according to the Los Angeles Times.

The city program initially will be open to 100 displaced families or their descendants who earn limited incomes, but city leaders hope their efforts will grow into a national model to address past racist policies.

The Los Angeles Times reported that more than one million people lost their homes in the first to decades of interstate highway construction.

It added: “Santa Monica’s act of civic penance is an attempt to recognize the harm done to largely Black communities during the post-World War II era of freeway building and urban renewal.”

While more than one million Americans gave up their homes for highways under eminent domain laws during the interstate construction boom, some historians claim that black neighborhoods were specifically targeted, arguing that the interstate system has a “racist history.”

Others note that while there were specific cases of racist removals — such as Bruce’s Beach, noted by the Bee, above — other examples lack evidence of racist motivation in urban planning. In some cases, faulty urban renewal projects were designed by planners who believed they were helping inner city populations.

Follow Penny Starr on Twitter