Facing pressure from parents and threats of criminal charges, some districts have ignored policies meant to prevent censorship. Librarians and students are pushing back.

KATY, Texas — From a secluded spot in her high school library, a 17-year-old girl spoke softly into her cellphone, worried that someone might overhear her say the things she’d hidden from her parents for years. They don’t know she’s queer, the student told a reporter, and given their past comments about homosexuality’s being a sin, she’s long feared they would learn her secret if they saw what she reads in the library.

That space, with its endless rows of books about characters from all sorts of backgrounds, has been her “safe haven,” she said — one of the few places where she feels completely free to be herself.

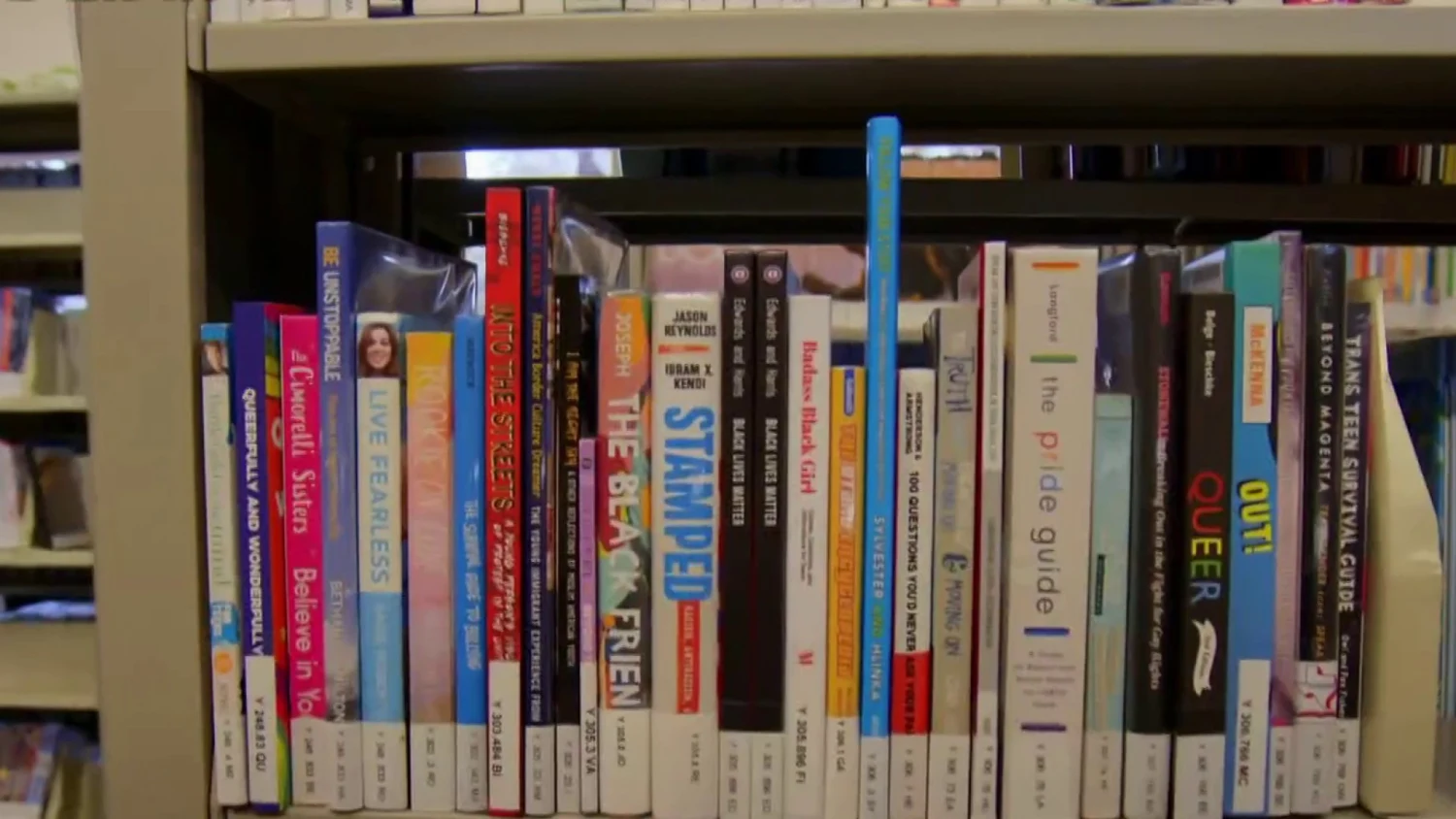

But books, including one of her recent favorites, have been vanishing from the shelves of Katy Independent School District libraries the past few months.

For more on this story, watch NBC’s “Nightly News with Lester Holt” tonight at 6:30 p.m. ET/5:30 p.m. CT.

Gone: “Jack of Hearts (and Other Parts),” a book she’d read last year about a gay teenager who isn’t shy about discussing his adventurous sex life. Also banished: “The Handsome Girl and Her Beautiful Boy,” “All Boys Aren’t Blue” and “Lawn Boy” — all coming-of-age stories that prominently feature LGBTQ characters and passages about sex. Some titles were removed after parents formally complained, but others were quietly banned by the district without official reviews.

“As I’ve struggled with my own identity as a queer person, it’s been really, really important to me that I have access to these books,” said the girl, whom NBC News is not naming to avoid revealing her sexuality. “And I’m sure it’s really important to other queer kids. You should be able to see yourself reflected on the page.”

Her safe haven is now a battleground in an unprecedented effort by parents and conservative politicians in Texas to ban books dealing with race, sexuality and gender from schools, an NBC News investigation has found. Hundreds of titles have been pulled from libraries across the state for review, sometimes over the objections of school librarians, several of whom told NBC News they face increasingly hostile work environments and mounting pressure to pre-emptively pull books that might draw complaints.

Records requests to nearly 100 school districts in the Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and Austin regions — a small sampling of the state’s 1,250 public school systems — revealed 75 formal requests by parents or community members to ban books from libraries during the first four months of this school year. In comparison, only one library book challenge was filed at those districts during the same time period a year earlier, records show. A handful of the districts reported more challenges this year than in the past two decades combined.

All but a few of the challenges this school year targeted books dealing with racism or sexuality, the majority of them featuring LGBTQ characters and explicit descriptions of sex. Many of the books under fire are newer titles, purchased by school librarians in recent years as part of a nationwide movement to diversify the content available to public school children.

“Why are we sexualizing our precious children?” a Katy parent said at a November school board meeting after she suggested that books about LGBTQ relationships are causing children to improperly question their gender identities and sexual orientations. “Why are our libraries filled with pornography?”

Another parent in Katy, a Houston suburb, asked the district to remove a children’s biography of Michelle Obama, arguing that it promotes “reverse racism” against white people, according to the records obtained by NBC News. A parent in the Dallas suburb of Prosper wanted the school district to ban a children’s picture book about the life of Black Olympian Wilma Rudolph, because it mentions racism that Rudolph faced growing up in Tennessee in the 1940s. In the affluent Eanes Independent School District in Austin, a parent proposed replacing four books about racism, including “How to Be an Antiracist,” by Ibram X. Kendi, with copies of the Bible.

Read more: Here are 50 books Texas parents want banned from school libraries

Similar debates are roiling communities across the country, fueled by parents, activists and Republican politicians who have mobilized against school programs and classroom lessons focused on LGBTQ issues and the legacy of racism in America. Last fall, some national groups involved in that effort — including No Left Turn in Education and Moms for Liberty — began circulating lists of school library books that they said were “indoctrinating kids to a dangerous ideology.”

And during his successful bid for governor in Virginia, Republican Glenn Youngkin made parents’ opposition to explicit books a central theme in the final stretch of his campaign, leading some GOP strategists to flag the issue as a winning strategy heading into the 2022 midterm elections.

The fight is particularly heated in Texas, where Republican state officials, including Gov. Greg Abbott, have gone as far as calling for criminal charges against any school staff member who provides children with access to young adult novels that some conservatives have labeled as “pornography.” Separately, state Rep. Matt Krause, a Republican, made a list of 850 titles dealing with racism or sexuality that might “make students feel discomfort” and demanded that Texas school districts investigate whether the books were in their libraries.

A group of Texas school librarians has launched a social media campaign to push back.

“There have always been efforts to censor books, but what we’re seeing right now is frankly unprecedented,” said Carolyn Foote, a retired school librarian in Austin who’s helping lead the #FReadom campaign. “A library is a place of voluntary inquiry. That means when a student walks in, they’re not forced to check out a book that they or their parents find objectionable. But they also don’t have authority to say what books should or shouldn’t be available to other students.”

Ten current or recently retired Texas school librarians who spoke to a reporter described growing fears that they could be attacked by parents on social media or threatened with criminal charges. Some said they’ve quietly removed LGBTQ-affirming books from shelves or declined to purchase new ones to avoid public criticism — raising fears about what free-speech advocates call a wave of “soft censorship” in Texas and across the country.

Five of the librarians said they were thinking about leaving the profession, and one already has. Sarah Chase, a longtime librarian at Carroll Senior High School in Southlake, a Fort Worth suburb, said the acrimony over books contributed to her decision to retire in December, months earlier than she’d planned.

“I’m no saint,” said Chase, 55. “I got out because I was afraid to stand up to the attacks. I didn’t want to get caught in somebody’s snare. Who wants to be called a pornographer? Who wants to be accused of being a pedophile or reported to the police for putting a book in a kid’s hand?”

In interviews and recorded comments at school board meetings, parents who’ve pushed for book removals described doing everything in their power to shield their children from sexually explicit content on the internet, only to discover it’s readily available in school libraries.

“It’s not censoring to guard minors from exposure to adult-themed books,” Kristen Mangus, a parent, said at a meeting in November of the Keller Independent School District Board of Trustees, a suburban district outside Fort Worth that’s fielded dozens of requests to ban books in recent months. “If they choose to check out from the public library with a parent, then so be it. But there is no reason whatsoever to have these books in our schools.”

Some protesting parents have insisted that their opposition is about sexually explicit books, regardless of the races or sexual orientations of the characters. They point out that some of the books being challenged feature heterosexual sex scenes. But in many instances, parents and GOP politicians have flagged books about racism and LGBTQ issues that don’t include explicit language, including some picture books about Black historical figures and transgender children.

Free speech advocates and authors deny that any of the books in question meet the legal definition of pornography. Although some include sexually explicit passages or drawings, those scenes are presented in the context of broader narratives and not for the explicit purpose of sexual stimulation, they said.

“Some parents want to pretend that books are the source of darkness in kids’ lives,” said Ashley Hope Pérez, author of the young adult novel “Out of Darkness,” which has been repeatedly targeted by Texas parents for its depiction of a rape scene and other mature content. “The reality for most kids is that difficulties, challenges, harm, oppression — those are present in their own lives, and books that reflect that reality can help to make them feel less alone.”

Several queer students, meanwhile, said the arguments by some parents, specifically the idea that it’s inappropriate for teenagers to read about LGBTQ sexual relationships, are making them feel unwelcome in their communities.

“Reading books or consuming any kind of media that has LGBTQ representation, it doesn’t turn people gay or make people turn out a certain way,” said Amber Kaul, a 17-year-old bisexual student in Katy. “I think reading those books helps kids realize that the feelings that they’ve already had are valid and OK, and I think that’s what a lot of these parents are opposed to.”

‘Short-circuiting’ the process

This fall wasn’t the first time Texas parents packed school board meeting rooms to complain about the corrupting influence of books.

Every year for nearly two decades beginning in the late 1990s, the Texas chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union surveyed every public and charter school in Texas to document attempts to ban library books. The annual reports paint a picture of past censorship movements, and make clear that the volume of challenges now hitting schools is unlike anything previously recorded in the state.

In the early 2000s, a conservative backlash to the Harry Potter book series, which some Christian leaders condemned as a satanic depiction of witchcraft, fueled a surge of book banning attempts in Texas, according to the ACLU data. But even at the peak of that wave, the Texas ACLU never documented more than 151 school library book challenges in one year. About half that many were documented in just the first four months of the 2021 school year at only a small sampling of Texas school districts, according to the records obtained by NBC News.

During the 2018-19 school year, the last time the ACLU conducted the censorship survey, Texas schools reported only 17 library book challenges statewide. Twice as many have been filed so far this school year at Keller ISD alone.

“I’ve been doing this work for 20 years, and I’ve never seen the volume of challenges that we’re seeing right now,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom at the American Library Association, which tracks attempts to ban library books nationwide.

Caldwell-Stone said the number of Texas book challenges documented in the records obtained by NBC News likely represents a vast undercount, because it doesn’t account for books that are being removed from shelves based on verbal complaints at board meetings or parent emails, often in violation of school district policies.

In response to past censorship movements, the American Library Association developed guidelines for schools to prevent the sudden and arbitrary removal of books. Under the guidelines, which have been adopted by most large districts in Texas and nationally, parents are asked to fill out forms explaining why they believe a book should be banned. Then a committee of school employees and community volunteers reviews the book in its entirety and determines whether it meets district standards, keeping in mind that a parent’s ability to control what students can read “extends only to his or her own child,” according to language included in most district policies.

A challenged book is supposed to remain on shelves and available to students while the committee deliberates, and the final decision should be made public, Caldwell-Stone said.

“What we’re seeing these days is a short-circuiting of that process, despite the fact that school boards often do have these reconsideration policies on their own books,” she said. “They’re ignoring them to respond to the controversy and the moral panics that they’re getting targeted with at school board meetings, and books are being abruptly removed.”

That scenario has been repeated at several Texas school districts in recent months, NBC News found. In December, the Denton Independent School District near Dallas made headlines when administrators pulled down a copy of “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” a memoir by queer Black author George M. Johnson, after learning that parents in neighboring towns had concerns about it. A district spokesperson, Julie Zwahr, said school officials are now reviewing a total of 11 library books to determine whether they are “pervasively vulgar,” even though the district has received only one formal book challenge this school year. The North East Independent School District in San Antonio hadn’t received any library book challenges from parents as of December, according to records provided to NBC News. But that month, administrators directed librarians to box up more than 400 titles dealing with race, sexuality and gender.

At a subsequent school board meeting, North East leaders said that they had pulled the books for review after Krause, the Republican lawmaker, distributed his list of 850 titles that he said violate new state laws governing how sex and race are addressed in Texas classrooms. North East spokesperson Aubrey Chancellor did not respond to a reporter’s request for comment, but told the Texas Tribune in December that the district asked staff to review books on Krause’s list “to ensure they did not have any obscene or vulgar material in them.”

“For us, this is not about politics or censorship, but rather about ensuring that parents choose what is appropriate for their minor children,” she said then.

In another instance, the Carroll Independent School District in Southlake, responding to an NBC News public records request, reported that it had received zero library book challenges in 2021. But emails reviewed by a reporter show that a parent had complained informally in August to a Carroll administrator and two school board members about the book, “Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out,” by Susan Kuklin.

“There is extreme sexual content in that book that isn’t even appropriate for me to put in an email,” the parent wrote.

Rather than requiring the mom to fill out a form to initiate the district’s formal library review process, Chase, the recently retired Carroll librarian, said an administrator shared the email with her and another librarian, and in order to avoid conflict, they agreed to remove the book from high school shelves.

“I hate that we did this, because we didn’t go through the formal review ourselves,” Chase said. “I think a lot of librarians are making decisions out of fear, and that puts us in a position of self-censorship.”

Book fight spreads from Virginia to Texas

Mary Ellen Cuzela, a mother of three in Katy, a sprawling and booming suburb outside Houston, had never thought much about what library books her kids might have access to at school. But in September, she heard then-candidate Youngkin mention a Virginia school district’s fight over “sexually explicit material in the library” during his campaign for governor against Democrat Terry McAuliffe.

Curious, Cuzela searched the Katy Independent School District’s catalog and was surprised to find that one of the books at the center of the Virginia fight, “Lawn Boy,” by Jonathan Evison, was available at her children’s high school.

Cuzela picked up a copy from the public library and “was absolutely amazed” by what she read, she said. The book, which traces the story of a Mexican American character’s journey to understanding his own sexuality and ethnic identity, was “filled with vulgarity,” Cuzela said, including dozens of four-letter words, explicit sexual references and a description of oral sex between fourth-grade boys during a church youth group meeting.

“I don’t care whether you’re straight, gay, transgender, gender fluid, any race,” she said. “That book had it all and was degrading for all kinds of people.”

She soon discovered that several other young adult books that had been targeted in Virginia and other Texas districts were available at Katy ISD. Cuzela shared her findings with some “like-minded parents,” and together they set out to get administrators to do something.

The school system, a diverse district of nearly 85,000 students, had already made national headlines that fall when administrators temporarily removed copies of “New Kid” and “Class Act” by Jerry Craft from school libraries after parents complained that the graphic novels, about Black seventh graders at a mostly white school, would indoctrinate students of color with a “victim mentality” and make some kids feel guilty for being white.

But Cuzela said she and her friends were having a hard time getting Katy administrators to take their concerns about sexually explicit books seriously. So they hatched a plan, and on Nov. 15, she and five other moms showed up at a Katy school board meeting with a stack of books.

One by one, they took turns at the lectern during public comments. Cuzela implored the board to audit all of the district’s library books and get rid of those that are too obscene to be read aloud in public.

“If you are filtering a student’s internet access,” she said, “why are we not filtering the library?”

Minutes later, Jennifer Adler, a mother of five, held up a copy of “Jack of Hearts (and Other Parts),” by L.C. Rosen, for the board to see. Adler explained that the book is about a character named Jack, who writes a teen sex advice column for an online site. Then she began reading.

“‘I wonder how he does it … how he gets all that D?’” Adler said, reading the first in a series of explicit excerpts referring to anal and oral sex.

After ending with a passage that included a detailed description of male genitalia and advice on how to give oral sex, she looked up at the board members, her voice shaking as she spoke.

“I cannot even imagine how I would feel if my child came home with this type of book,” said Adler, whose oldest child is in middle school. “We cannot unread this type of content, and I would like to protect my kids’ hearts and minds from this.”

The audience, packed with parents and community members who shared her concerns, erupted in applause.

‘Taking the matter seriously’

Rosen, the author of “Jack of Hearts,” wasn’t surprised when he heard about the demands to ban his book in Katy. Like other authors whose books have been targeted in recent months, Rosen said parents have been reading passages out of context.

At the time of the book’s release in 2015, the School Library Journal, a magazine that districts rely on to select library books, wrote that the dearth of “sex positive queer literature” made “Jack of Hearts” an “essential addition to library collections that serve teens.”

The sex advice columns written by the book’s protagonist are part of a bigger narrative that’s meant to empower queer teens and help them feel safe talking about their sexuality, Rosen said.

All of the questions answered in Jack’s advice column were submitted by real students, Rosen said. And the author consulted with sex education experts to write Jack’s responses, with the goal of providing LGBTQ teens with practical information that’s often omitted from sex ed classes.

“I think it’s troubling when they can’t distinguish between porn — which is not meant for education — and a book like mine that’s trying to educate teenagers and tell them, ‘It’s OK to have these desires; here’s how to act on them consensually and safely,’” Rosen said.

Cuzela and her allies, who denied that they were specifically targeting LGBTQ content, saw things differently. And so did Katy ISD leaders, according to internal messages obtained by NBC News.

Rather than asking the parents to file formal challenges or forming a committee to review the books they’d read aloud, Darlene Rankin, the district’s director of instructional technology, sent an email the day after the school board meeting directing school staff to immediately remove two titles from all libraries: “Jack of Hearts” and “Forever for a Year,” by B.T. Gottfred.

“If these books are currently checked out to students, you must contact the student in order to have the book returned,” wrote Rankin, who declined an interview request.

In the weeks that followed, Katy parents continued applying pressure, calling on the district not only to audit libraries for vulgar content, but to overhaul the selection process to de-emphasize recommendations from prominent book review journals, arguing that those groups are pushing a liberal agenda.

In early December, Superintendent Ken Gregorski responded to those demands, announcing in a letter to all parents that the district was launching a broad review of its library books to remove any that might be considered “pervasively vulgar.” Gregorski, who declined to be interviewed, invited parents to report other books they want removed and assured them that he would “ensure the district is taking the matter seriously and putting into action the plans that resolve the issues for which we are all concerned.”

In total this school year, according to internal messages, the district has launched reviews into at least 30 library books and so far has deemed nine to be inappropriate for students at any grade level, including five that prominently feature LGBTQ characters. Several other books, including “This Is Your Time,” by the civil rights era icon Ruby Bridges, were deemed inappropriate or too mature for young children and removed from either elementary or middle school libraries.

Most of these reviews were opened without a formal book challenge, records show, even though one is required under Katy ISD’s local policy.

In at least two instances, according to three district employees with knowledge of the review process, senior district administrators have ordered books to be removed from libraries even after review committees examined them and voted to keep them in schools. The district employees spoke to a reporter on the condition of anonymity, worried that they might be disciplined for sharing their concerns publicly.

In response to detailed written questions, Katy ISD spokesperson Maria DiPetta wrote that “the district will have to kindly pass on your request.”

Cuzela said she’s pleased that the district is now taking her concerns seriously and hopes administrators go further. Although she doesn’t believe most librarians are knowingly stocking shelves with “pornographic material,” she agrees with Abbott’s call for criminal charges against any who do, including in Katy.

“We have laws in Texas against providing sexually explicit material to children,” she said. “It’s a law on the books, and if they knowingly are providing this, they need to be advised and investigated.”

Foote, the retired school librarian who’s leading a statewide campaign against book bans, said Katy’s approach is flawed, not only because it lacks transparency and opens the door for additional censorship attempts, but because of the signal it sends.

“You can’t overstate the impact these decisions can have on LGBTQ students and even teachers,” Foote said. “Intentional or not, these bans are sending a message to them about their place in the community.”

On the phone at her high school library, the queer Katy student who worries her parents won’t accept her for who she is said she was outraged when she found out librarians had started removing books — especially “Jack of Hearts.”

“For me, a lot of these books offer hope,” the student said. “I’m going to be going to college soon, and I’m really looking forward to that and the freedom that it offers. Until then, my greatest adventure is going to be through reading.”

Like other library books she’d read that centered on LGBTQ characters, the student said “Jack of Hearts” gave her a sense of validation. The main character, a 17-year-old who isn’t shy about his love for partying, makeup and boys, was a sharp contrast to her own high school experience, constantly on guard against saying or doing anything that might lead to her being outed.

The book, she said, made her feel less alone.

Rosen, the author, has heard similar things from other teenagers. When he gets those messages, he said he usually replies to say that he hopes things will get better.

But then he adds: “I can’t promise that it will.”