“As a person whose family is laid to rest in Babi Yar, I am in excruciating pain watching the news. I never thought this could happen in a million years,” one survivor said.

Pavel Averbukh, 86, has lived near New York’s Brighton Beach neighborhood for the past three decades, but when he watches the news about Ukraine, he is transported back to being a 6-year-old in Odessa, Ukraine.

“My heart is bleeding from the pain that I’m experiencing by observing this,” he said in Russian, according to a translator. “The consistent, perpetual fear of being killed and exterminated at any moment is something I’m reliving consistently while watching the news.”

Averbukh is a Holocaust survivor. He said he remembers the day in 1941 when he was lucky enough to get on the last boat out of Odessa. His grandmother, who refused to evacuate Ukraine at the time, was killed during World War II.

As Averbukh attends activities for older adults at Kings Bay Y in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, he said he worries for the safety of many of his cousins who live nearly 5,000 miles away in Ukraine.

He is not alone in this experience. Brighton Beach is home to the highest concentration of Russian-speaking immigrants in the United States. This area is nicknamed “Little Odessa” after the port city in Ukraine. On these streets, Russian and Ukrainian are sometimes more commonly spoken than English. The American Jewish Committee estimates there are 300,000 Russian-speaking Jews in New York.

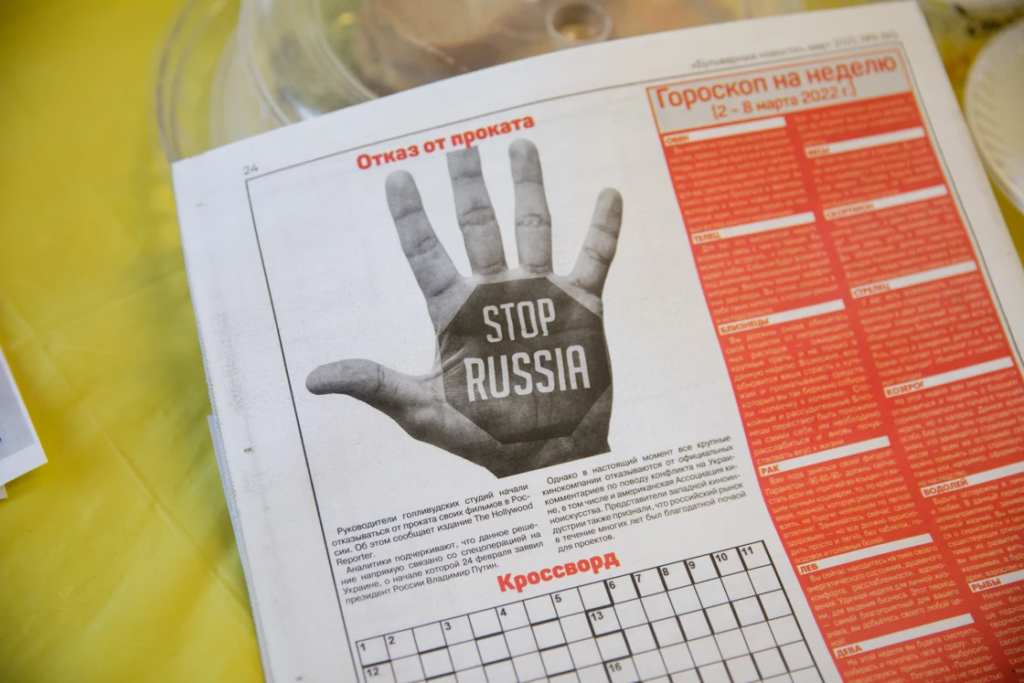

Stores along Brighton Beach Avenue display Ukrainian flags and QR codes for charities supporting the country and its people. Outside the Brighton Bazaar grocery store, a sign in English reads, “Stop Putin.” It is next to a sign in Russian that translates to “No war.” The Taste of Russia supermarket has taken down its awning as an act of solidarity following the Russian invasion.

As the older adults at Kings Bay Y dance and read local newspapers in Russian, the war in Ukraine is ever present to this group, many of whom are Holocaust survivors like Averbukh.

The heightened anxiety and grief Averbukh is experiencing is not uncommon. Many Holocaust survivors feel as if they are retraumatized by the Russian invasion.

Vladimir Brovarnik was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1937 and survived the Holocaust by evacuating to Yerevan, the capital of Armenia. He has relatives who were not as lucky as he was to escape and were murdered at Babi Yar, the site where 33,771 Jews were killed over a two-day period.

On March 1, a Russian missile strike that appeared to target a TV tower in Ukraine’s capital struck the vicinity of the Babi Yar Holocaust memorial.

“As a person whose family is laid to rest in Babi Yar, I am in excruciating pain watching the news,” said Brovarnik, who, along with other Holocaust survivors interviewed by NBC News, spoke in Russian. “I never thought this could happen in a million years.”

According to Masha Pearl, the executive director of The Blue Card, a national organization that provides financial assistance to “poverty-stricken Holocaust survivors,” “Many of the Russian-speaking Holocaust survivors and the Ukrainian Holocaust survivors are experiencing and reliving trauma, and this is triggering PTSD from their wartime years.”

Anatoly Sukhorukov, 78, said he “absolutely cannot watch any of this without tearing up and crying immediately.”

Sukhorukov was born into a Jewish family in Moscow toward the end of World War II and was evacuated to River Ural. He said he is having a hard time sleeping because of what is happening in Ukraine.

He said he feels deeply disturbed by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “denazification” claims.

“I feel it’s a disgusting lie,” Sukhorukov said. “It’s a strategy for Putin. I feel that Putin is playing on the feelings of Russians who truly despise Nazis.”

Daniel Zeltser, the CEO of the Kings Bay Y, works closely with the Russian and Ukrainian Jewish community. He said for Holocaust survivors and their descendents, “these notions of ‘denazifying’ Ukraine and then seeing Babi Yar bombed make the words of ‘never again’ almost meaningless.”

The angst is felt across all generations who have Ukrainian or Russian Jewish backgrounds and who have advocated for the idea that events like the Holocaust must “never again” take place.

Mikhail Zaretser, 17, is a first-generation Ukrainian American Jew who grew up in Brighton Beach. He said he has learned from the past and believes it’s his job as the next generation to speak up: “We say ‘never again,’ and then when stuff like this happens, it’s like, is the world really moving in a positive direction?”

Zaretser has spent many summers in Ukraine. Some of his friends have been split from their families and drafted to the army. His mother, Sabina Kirtich, who immigrated to Brighton Beach from Ukraine in 1997, has a lot of family and friends who live in all different parts of Ukraine.

Her outlook is symbolic of the Ukrainian resistance shown thus far: “We survived the pandemic; we will survive the war. We are survivors.”