The towering container ships and oil tankers that sail in and out of San Francisco Bay have a little-known dark side: They are a leading cause of death for whales that migrate along the coast between Mexico or Central America and Alaska.

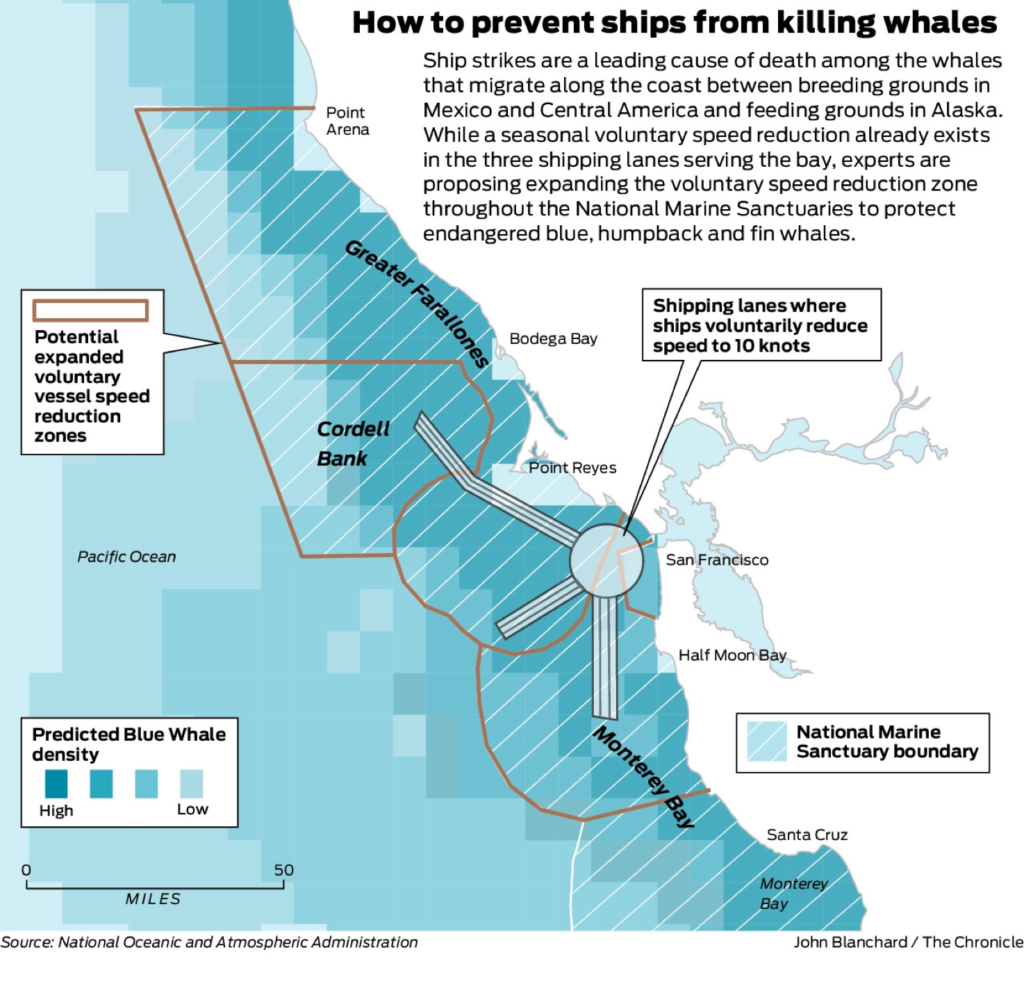

But there’s a way to reduce the number of whales that often wash up, bloated and mangled, on Bay Area beaches this time of year, experts say. A new report recommends slowing the speed of ships on a large stretch of the coast, from Pigeon Point in San Mateo County to Point Arena in Mendocino County. The idea is to give whales a chance to escape mortal injury.

“A lot of the time, mariners don’t know that they’ve even hit a whale. Cargo ships really are like skyscrapers,” said Jessica Morten, a resource protection specialist for the Greater Farallones Association, a conservation group that supports the National Marine Sanctuary of the same name. “On the surface of the ocean, a blue whale, even though it’s enormous to us, is really not enormous.”

Morten is part of a working group charged with cutting the risk of lethal ship strikes to endangered whales by 50% in the two marine sanctuaries that hug the coast. Last month, the group — composed of scientists, conservationists and representatives of the fishing and shipping industries — recommended a year-round, voluntary speed reduction within the Greater Farallones and Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuaries, as well as the northern part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

Since 2013, there has been a voluntary vessel speed reduction to 10 knots (about 11 mph) in place for large ships in the three shipping lanes that jut out of the bay — but only from May to November, during whale migration season. Once the ships exit the lanes, they tend to speed up and fan out into whale habitat.

The ship-strike issue has gotten more attention as the number of dead whales washed up on Bay Area beaches has increased in recent years, from 11 in 2018 to 21 last year. Ship strikes are a leading cause of whale death, along with entanglement in fishing gear and malnutrition, according to the nonprofit Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito. The increase includes many gray whales, a population that isn’t endangered but is experiencing what wildlife managers call an unusual mortality event, with a high number of deaths from various reasons since 2019.

Experts say the ever-growing demand for imported goods will continue to put the giant cetaceans in harm’s way. Ship traffic went down during the pandemic, from 3,452 ships entering the bay in 2018 to 2,893 in 2020, according to the nonprofit industry group Marine Exchange of the San Francisco Bay Region. But that’s still an average of eight large ships each day. Potential collisions are especially a concern as evidence grows that some whales, especially juvenile humpbacks, are staying in the Bay Area year-round.

“We have growing whale populations off of our coast, and we have increased shipping activity and commerce activity. So I think the risk is much higher (than in the past),” said Kathi George, a member of the working group and director of field operations and response at the Marine Mammal Center. In partnership with the California Academy of Sciences, George and her team do necropsies — animal autopsies — on whales that wash up on shore.

“In the case of a vessel strike, it is not a very pretty sight,” George said. “I’ve seen broken bones, ribs not attached any more, vertebrae separated. It’s a pretty violent thing that happens when a whale is hit by a ship.”

Each year, as many as 83 endangered whales — humpback, blue and fin whales — are killed by ships on the West Coast, according to projections by the Petaluma organization Point Blue Conservation Science. But because their carcasses sink quickly, only a fraction are seen and reported, experts say. Also, dead whales often make it to shore in a severely decomposed state, making it difficult to confirm the cause of death.

From 2011 to 2021 an average of only 10 whales a year along the West Coast were officially recorded as being struck by vessels, and not all of those whales died, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The list includes gray, minke and sei whales in addition to endangered whales.

Many of those whales begin migrating this time of year, and they sometimes end up dead on local beaches. George and her colleagues have necropsy equipment packed and ready to go, like firefighters waiting at the station. Ten to 20 people are usually involved in a necropsy, more if the whale washes up on a busy beach to help keep onlookers (and curious dogs) away from the sharp tools and difficult work involved.

“A team will methodically open up the whale. They’ll peel down the layers of blubber,” George said. “Sometimes people literally get into the whale to look at the different bones, organs, etc. to understand what happened.”

Broken bones are a major indicator of a vessel strike, but only if there are also signs of tissue damage or pooled blood inside, indicating the whale was struck before death rather than after, she said.

Though vessel strikes are only one threat to whales, the working group thinks extending the recommended vessel speed reduction zone to nearby National Marine Sanctuaries year-round will make a difference.

The current voluntary vessel speed reduction in the three shipping lanes that was instituted in 2013 probably lowered blue whale deaths within the shipping lanes by 11% to 13% and humpback whale deaths by 9% to 10% in 2016-17, according to Point Blue.

“That northern lane really does spit out traffic where we don’t want it to be,” said Morten, into a blue whale hot spot near Point Reyes.

Shipping companies are getting on board. As of 2020, 64% of ships complied with the voluntary speed reduction in the shipping lanes.

“We’ve gotten more carriers on board — greater outreach and greater education as to why this is a program to participate in,” said Jacqueline Moore, vice president of the Pacific Merchant Shipping Association, an industry group that supports extending the voluntary speed reduction zone year-round to the sanctuaries.

In 2019, a similar change was made in Southern California, when the voluntary vessel speed reduction was expanded to an area from Santa Barbara County to Orange County, though only seasonally. On the East Coast, NOAA instituted mandatory vessel speed limits to protect the critically endangered right whale.

The conservation group Center for Biological Diversity has called for mandatory speed limits in shipping lanes at the Port of Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay in a petition to National Marine Fisheries Service and a lawsuit against the U.S. Coast Guard and NMFS, arguing that the number of whales killed each year exceeds what the populations can withstand and still recover.

“There’s a mentality of bending over backwards to avoid these mandatory ship speeds. It’s perplexing,” said Brian Segee, endangered species program legal director at Center for Biological Diversity. “It’s a highway at sea. Just as highways on land need rules that are enforced. It’s the same with the ships at sea.”

The superintendent of the Cordell Bank and Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuaries will consider the working group’s recommendations and probably make a decision by May, Morten said. If the changes are adopted quickly, they could still save some whales this coming migration season, supporters say.

“Whales have an awful lot to tell us about the health of the ocean,” George said. “We need to do what we can to reduce the human impacts on the whales.”