The story of Latino parents who successfully fought school segregation and discrimination went unexamined for a century. A new sculpture honors the Maestas decision of 1914.

All Francisco Maestas wanted was for his children to get a quality education. When his local school district in Alamosa, Colorado, insisted he send his kids to the so-called Mexican School, Maestas fought the district in court and won.

The Maestas case was decided in 1914. Experts say it was one of the country’s first successful school desegregation cases — and the earliest known one so far involving Mexican Americans.

For over a hundred years, this story of Latino parents fighting for their children’s education was lost to history — until recently.

A three-dimensional sculpture depicting the Maestas children will be installed Thursday in the State Capitol in Denver in honor of the 108th anniversary of the decision in the case. The statue then will tour other parts of the state.

“This case lay dormant for a century, and it took some strong efforts by academics to bring it to light,” said Ron Maestas, a retired educator and descendant of the Maestas family. “To me, Francisco Maestas gives us a lesson in courage, a simple man standing up against inequity. He stood up for his kids, because he wanted safety and education for them.”

Fighting back

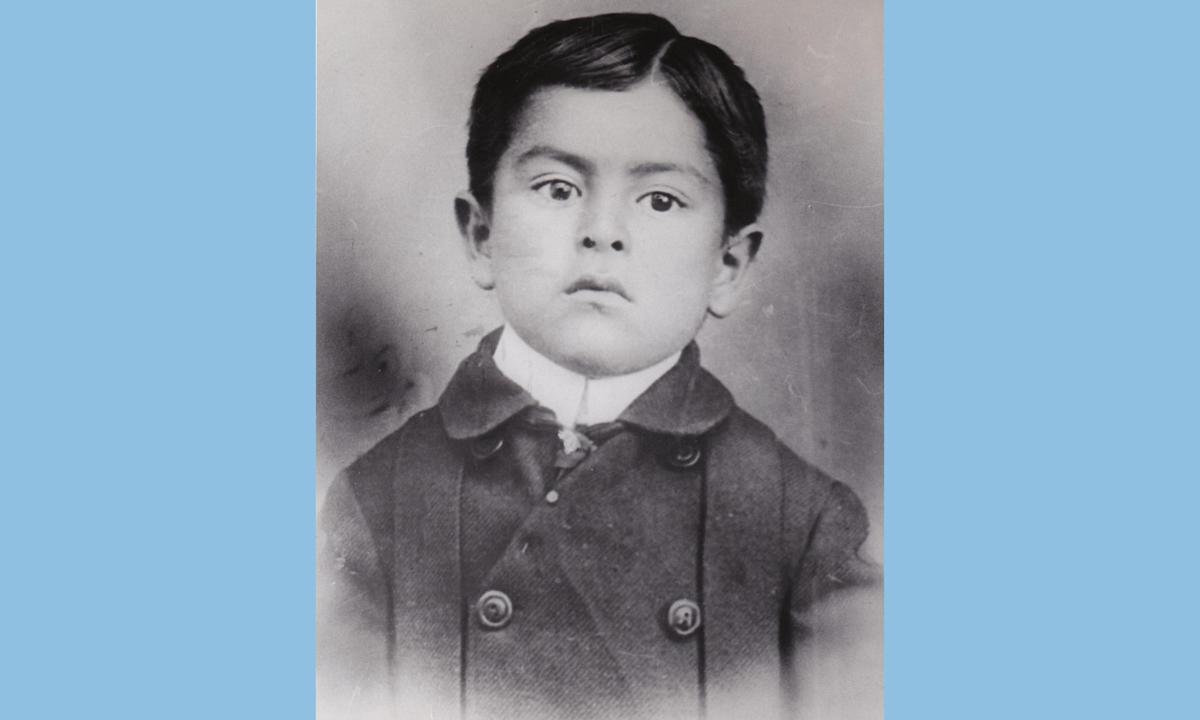

In 1913, Francisco Maestas tried to enroll his son Miguel, 11, at the school closest to their home in Alamosa, a small town in southern Colorado. But school officials insisted that Miguel attend the segregated “Mexican school,” which required a longer walk across railroad tracks. Maestas submitted a petition, with 180 signatures, challenging the decision. He was turned down again, so he and other Mexican American parents pulled their children out of school in protest, a boycott that would last for months. The parents banded together, raised money for a lawyer and took their case to court.

The group of parents alleged that racial prejudice was the reason Mexican American students were forced to attend an inferior school. The school board argued that because Mexicans were considered white, there could be no racial discrimination.

Instead, the school district said, the students were separated based on their language abilities. But during the trial, the families proved the school district wrong. Several children, including Miguel Maestas, took the stand and demonstrated their English-language fluency.

Eventually, District Judge Charles Holbrook ruled in favor of the families.

“Spanish speaking people believe that their children are excluded from the two English speaking schools, upon account of race,” Holbrook noted to the court, asserting that this “feeling must be eradicated before the school can reach its greatest efficiency.”

The judge said the English-speaking Mexican American children had the right to attend public schools near their homes or schools of their choice in the Alamosa district.

‘Latino history has been buried’

Holbrook’s decision made local headlines, but the case then faded into obscurity.

Decades later, Gonzalo Guzmán, a visiting assistant professor of educational studies at Colgate University, came across a reference to the Maestas case in an archived Wyoming newspaper. Intrigued, he consulted the original court documents, and he and several colleagues published their findings in an academic journal in 2017.

“It was amazing, really, that this case was rediscovered as part of a slight reference in an old newspaper,” Guzmán said. “But our history did not occur by accident. We are not an afterthought. The fact that people don’t know about it is by design. Latino history has been buried.”

Guzmán said Latinos are often left out of conventional American history scholarship.

“It is a statement about the way that Latinos are viewed in this country that most curriculums, even at the college level, do not include us,” he said. “There is this idea that we are not worthy of being discussed or being studied, that we are not part of the common public narrative.”

Many Latino students, Guzmán said, study their heritage on their own, through independent research. “But why do we have to leave the school system to find our own history?” he asked.

The case occurred long before the country had any concept of the words “Latino” or “Hispanic.” Most of the families involved in the case most likely self-identified through their heritage as “mexicano” (Mexican), Spanish American or “Hispano.”

In much of the Southwest and the West, including Colorado, many Hispanic families can trace their roots back for generations, some as far as the 16th century.

The lawsuit itself was tried years before other legal challenges by Latino families against school districts in Texas and California. It predates the celebrated Mendez case, in which Mexican American families in California fought for equal access to education, by 33 years — and it paved the way for the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision.

“The Maestas case tells us there is a history in Colorado of Hispanics using the courts and the Legislature to advance their rights,” Colorado District Judge Martín Gonzales said. “It deserves attention because it shows how long the gente [people] have been struggling to reach true equality.”

In his view, the case is not better known because the school district did not file an appeal. As a result, its impact was local, and it was never written up extensively in judicial records.

Scholars say the case is important because it offers evidence of the history of Latino advocacy, especially of how parents fought for their children’s right to education. It can also be seen as relevant today given the controversies over ethnic studies programs and critical race theory.

In 2020, the Colorado Senate passed a resolution recognizing the significance of the Maestas case. Rubén Donato, a professor of education at the University of Colorado Boulder, hopes the commemoration will lead to greater public awareness of it.

“When Americans think about school desegregation, most people have some familiarity with Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark case brought by African Americans,” he said. “Brown has become part of the public imagination. … But most of us have not had the opportunity to learn about the educational challenges faced by Mexican Americans.”

Donato said Mexican Americans may have brought more lawsuits in the past that simply have not been discovered and examined.

Donato said he is optimistic that the case, and others like it, will someday be incorporated into school curriculums.

These days, Alamosa County is home to about 16,000 people, 47 percent of whom identify as Latino. Some residents say inequality persists in the area.

“The amount of funding that our schools get is problematic. There are still communities that do not have reliable Wi-Fi,” said Katie Dokson, whose family has lived in the San Luis Valley for seven generations. “We have communities in this part of the state that suffer from disparities in infrastructure, representation and education.”

A bronze relief sculpture marking the case is scheduled to be installed in the Alamosa County Courthouse in October.

Remembering the case matters to Dokson, because “there is not enough comprehensive documentation of the American Southwest.”

“It is a passion project for me to learn about my heritage and pass it on to my children,” she said. “Why wouldn’t we want to learn as much about the history of America as possible?”