This obituary is part of a series about people who have died in the coronavirus pandemic.

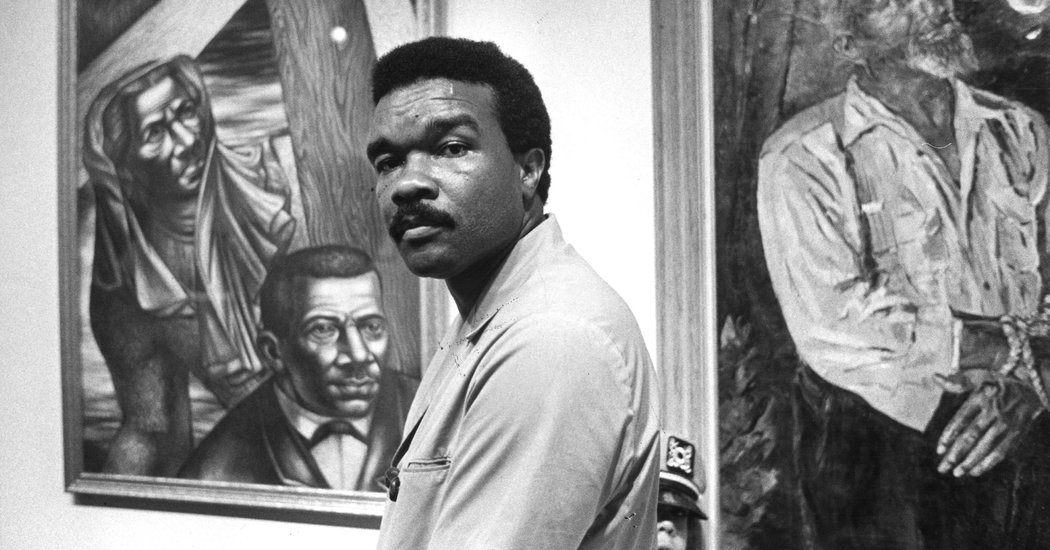

David C. Driskell, an artist, art historian and curator who was pivotal in bringing recognition to African-American art and its importance in the broader story of art in the United States and beyond, died on April 1 in a hospital near his home in Hyattsville, Md. He was 88.

The University of Maryland, where he held the title of distinguished university professor of art, said in a posting on its website that the cause was the coronavirus.

Professor Driskell was teaching at Fisk University in Nashville in the mid-1970s when he began putting together “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950,” a landmark exhibition that was first mounted at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and that later traveled to the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta and the Brooklyn Museum.

It was a sweeping show featuring more than 200 works by 63 named artists as well as anonymous crafts workers. Some critics found it too scattershot — “as an anthology, it needs serious editing,” Grace Glueck wrote in The New York Times — but Professor Driskell maintained that that was by design.

“I was not looking for a unified theme,” he told The Times in 1977. “And this, of course, usually upsets the critics because they want to see a continuous kind of thing. I was looking for a body of work which showed first of all that blacks had been stable participants in American visual culture for more than 200 years, and by stable participants I simply mean that in many cases they had been the backbone.”

Earlier scholars, including Professor Driskell’s mentor, James A. Porter, had done pioneering work on the history of black art and artists, but Professor Driskell pushed further.

“Driskell did not so much discover the best known African-American artists as he did establish African-American art as a legitimate and distinct field of study,” Keith Morrison, who was then dean of the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, wrote in the foreword to “David C. Driskell: Artist and Scholar,” a 2006 biography by Julie L. McGee.READ A Rich (Very Rich) History of the Jewish Dairy Restaurant – Serialpressit (News)

“Very few scholars in the annals of human history can be said to have established an entire field of study,” he added, but Professor Driskell’s show “did just that.”

David Clyde Driskell (pronounced like Driscol) was born on June 7, 1931, in Eatonton, Ga., southeast of Atlanta. His father, George Washington Driskell, was a minister, and his mother, Mary Cloud Driskell, was a homemaker. His mother, he said, passed on to him a washing pot that had belonged to her grandmother.

“And she said Grandma Leathy would tell her stories about this pot,” Professor Driskell said in an oral history recorded in 2009 for the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art. “This was the pot that her mother used to cover her head to pray in slavery so nobody would hear her praying for freedom.”

When he was 5 the family moved to western North Carolina, where he attended segregated schools. The high school he attended required a 35-mile bus ride each way.

He had received a $90 scholarship to Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., but at the last minute he decided he wanted to go to Howard University in Washington. He arrived three weeks after classes had begun, having not gone through the application process.

“They tried to be firm with me,” he recalled, “and said: ‘School has been in session for three weeks. You can’t just come to college. You have to make an application.’ I insisted on staying. I said, ‘Well, I’m here; give me an application.’”

He started out studying history, but in 1951 he took his first art course, a drawing class. One day a distinguished-looking man dropped in on the class and began admiring a drawing over Professor Driskell’s shoulder. Realizing that Professor Driskell was not one of the regular art students, the man asked him what his major was.READ How and why blockchain know-how is a tricky nut to crack for hackers

“I said history,” Professor Driskell recalled. “And he looked at my drawing and looked at me and said, ‘You don’t belong over there; you belong here.’”

The man was James Porter, the acclaimed African-American art historian and a teacher at the university. Professor Driskell studied under him and other notable scholars on the Howard faculty, and in 1953 he received a summer scholarship to the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine.

He graduated from Howard with a bachelor’s degree in art in 1955 and taught for several years at Talladega College in Alabama. He earned a master’s degree from the Catholic University of America in Washington in 1962, the same year he joined the Howard faculty. He moved to Fisk in 1966.

In 1949, Fisk had received a substantial gift of art from Georgia O’Keeffe, including several of her own works, and Professor Driskell took an active role in overseeing and maintaining it.

In 1970 the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York staged an O’Keeffe retrospective and borrowed one of her paintings from Fisk. That got Professor Driskell an invitation to a highbrow dinner at a Fifth Avenue apartment to celebrate the opening.

“Everybody was driving up in big limousines and cars,” he recalled. “I arrived in a taxi. The doorman was ushering people in. When I arrived, the doorman asked me, as I was coming in, ‘Oh, are you reporting to work?’”

It was an experience that underscored for him that the art world was still largely white. Professor Driskell began to change that with the 1976 exhibition, although he acknowledged the disconnect between arguing that black artists had always been important and then separating out their work for its own exhibition.

“We don’t go around saying ‘white art,’” he told The Times in 1977, “but I think it’s very important for us to keep saying ‘black art’ until it becomes recognized as American art.”READ Nominations shut in Telangana; KCR’s son Rama Rao, Cong working prez Revanth Reddy file papers

As for his own art, Professor Driskell worked in watercolor, gouache, collage and more. A 1993 exhibition at the Midtown Payson gallery in Manhattan featured works of his with nature as a central theme, vermilion and greens dominating.

“Painted strips of canvas and paper are used side by side as collage material, and both are often further worked with fine calligraphic strokes,” Holland Cotter wrote in a review in The New York Times. “The sense of hands-on intimacy that results is the work’s most engaging feature.”

Professor Driskell was also an art collector, and not merely a casual one. He was said to own one of the finest private collections of African-American art in the world. It numbered some 450 pieces in 1998, when the University of Maryland, where Professor Driskell had been a professor since 1977, mounted “Narratives of African American Art and Identity: The David C. Driskell Collection,” an exhibition of 100 works that later toured to Dallas, San Francisco and elsewhere.

In 2001 the University of Maryland established the David C. Driskell Center, which documents and presents African-American art and holds the Driskell archive.

He is survived by his wife, Thelma Grace Driskell, whom he married in 1952; two daughters, Daviryne McNeill and Daphne Coles; five grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

As a collector, Professor Driskell was interested in not only black artists. He liked to scour out-of-the-way shops, and he knew a bargain when he saw one. In 2003 he told The Baltimore Sun how he had come to acquire a Rembrandt while strolling through Copenhagen.

He saw it in the window of a quirky-looking shop, he recalled. The owner thought it was just a facsimile.

“But I had just studied Rembrandt’s prints at The Hague,” Professor Driskell recalled, “and I could see this one had ink qualities different from a reproduction. When he said $10, I said, ‘I’ll take it.’”