There’s a long history of medicine and government choosing “who shall live” in the name of science and economics.

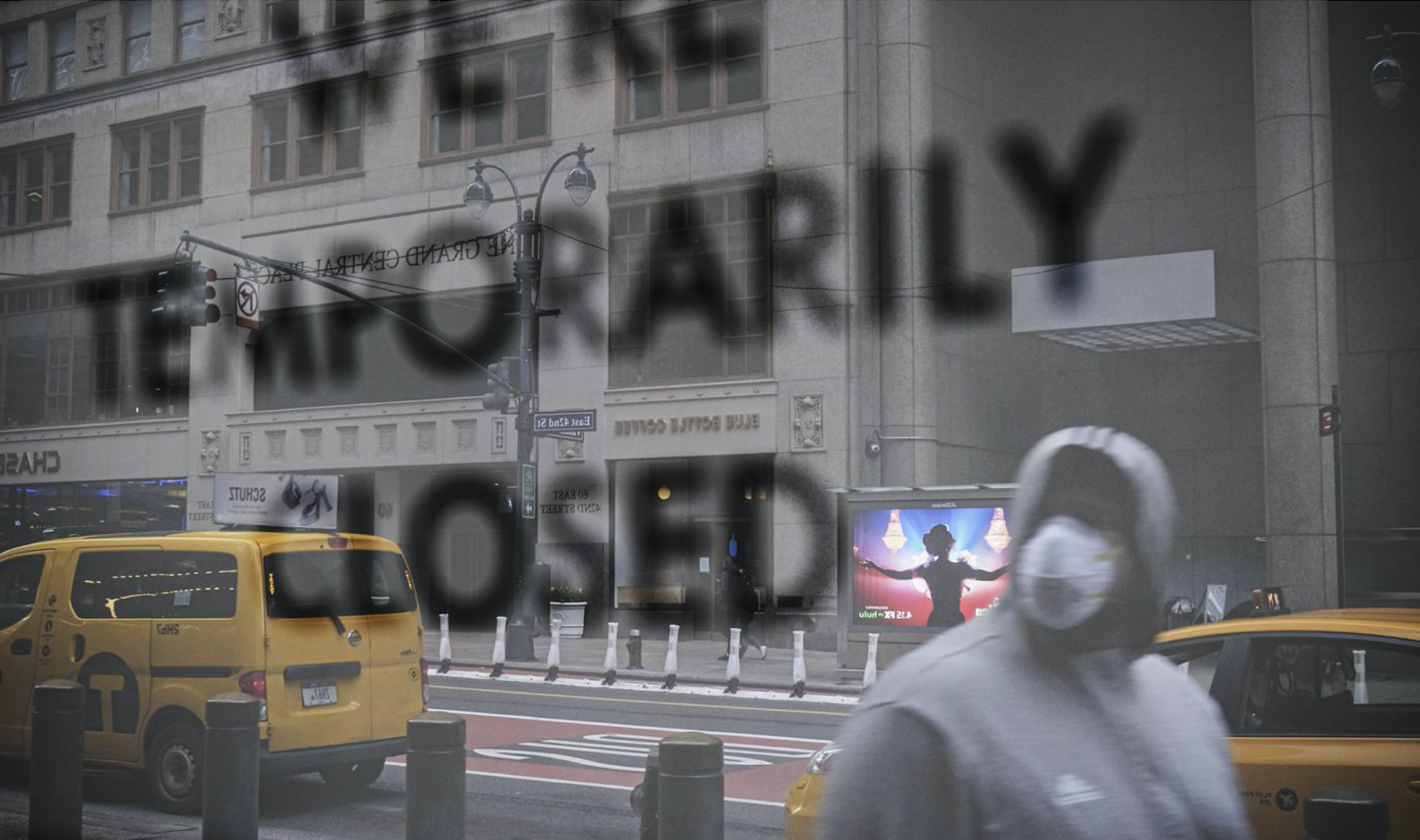

As of April 28, the United States surpassed 1 million confirmed coronavirus cases. But this hasn’t stopped more than half of US states from partially reopening or making plans to reopen soon. Prematurely restarting businesses means new virus cases will arise, health officials say, especially in the face of insufficient testing. This puts the country’s most vulnerable populations — black, Latinx, poor, elderly, disabled — at greater risk of infection and death.

For the black community, the decision to reopen — despite the alarming data that shows they are disproportionately suffering from the disease (black people make up 30 percent of coronavirus cases, according to the CDC, even though they represent just 13 percent of the US population) — fuels the community’s distrust of government and health leadership. It harks back to cruel historical practices that used black bodies as scientific Silly Putty.

The event most cited to explain the historical distrust is the US Public Health Service’s (PHS) syphilis study at the Tuskegee Institute, which began in 1932 and continued for 40 years, until it was exposed as ethically unjustified. The study tracked 399 black men in rural Macon County, Alabama, who had syphilis and another 201 who were supposedly in a control group. PHS never informed the participants that they had the disease and simply told the men they would be treated for “bad blood,” a catchall phrase for various illnesses. Ultimately, the federal government would surveil the men to determine syphilis’s impact on the body’s organ systems when left untreated.

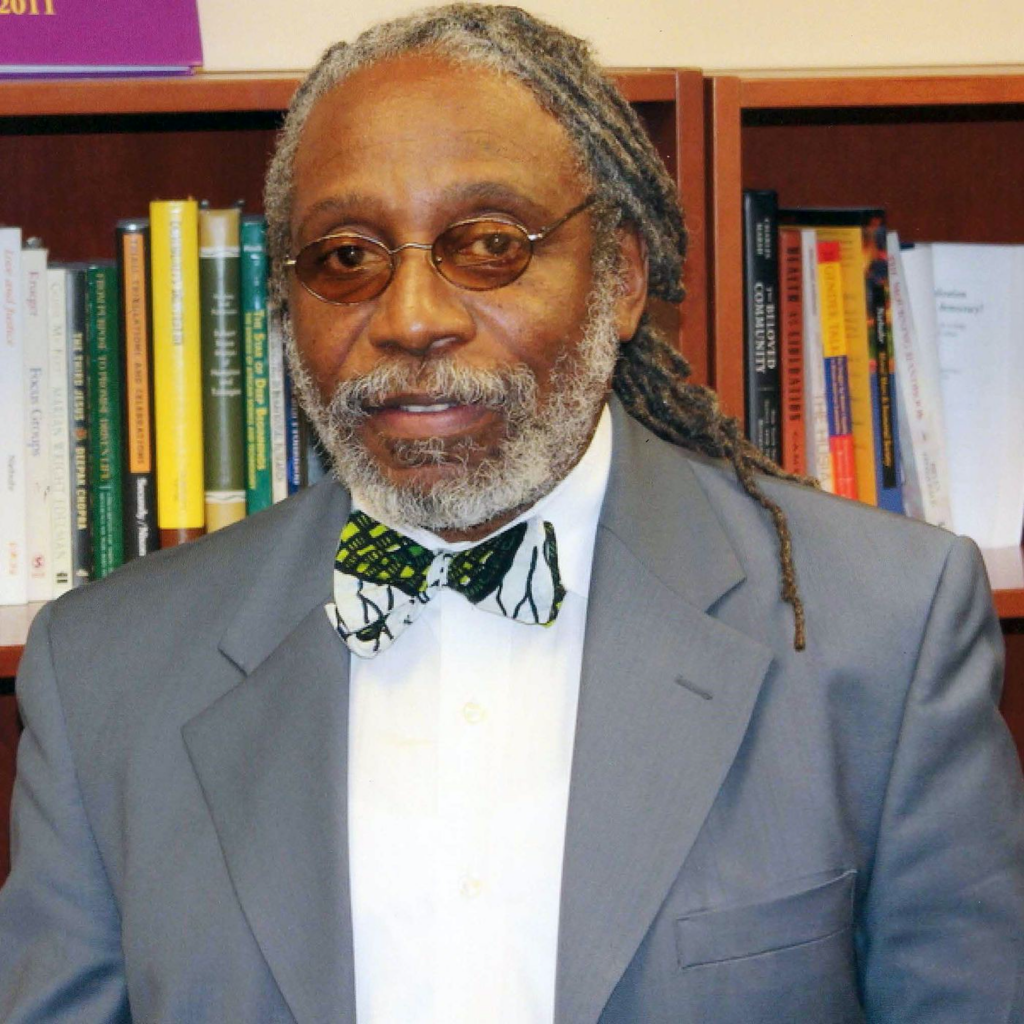

As the director of Tuskegee University’s National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care, Reuben C. Warren knows this history all too well. According to Warren, PHS fractured the relationship between the federal government and the black community by lying and withholding treatment — and marring Tuskegee’s history in the process, an institution founded by the renowned black educator Booker T. Washington for the academic and vocational training of black professionals. In 1997, decades after the study was exposed, Warren, then the associate director of minority health at the CDC, a position he held for 20 years, was part of a coalition of scientists and public health officials that called on President Bill Clinton for an apology. Following the apology, the federal government, at the coalition’s request, established the center Warren now heads to ensure that a project like the syphilis study wouldn’t happen again.

Warren says that at this moment in the coronavirus pandemic, governors are now choosing “who shall live” by reopening states, drawing parallels to moments like the Tuskegee syphilis study. Warren explains why this is a matter of ethics and a false choice between health and economics, as the issue of black distrust only worsens. (Our interview has been edited and condensed.)

Fabiola Cineas

When you first heard about the novel coronavirus, particularly about how it was taking the lives of black people at a disproportionate rate, what was your initial reaction?

Reuben C. Warren

My initial reaction was: “more of the same.” I was not surprised. Nor was I surprised that initially public health officials and political officials did not want to collect race and ethnicity data because they knew what data would tell them. You count what you think is important, and you ignore what you don’t think is important. They refused to do something until the demand to collect data grew.

Many people will say black people have a disproportionate burden of disease, like heart disease and diabetes. All that’s true, but the current challenge is black and Hispanic folks continue to be at risk. They are the workers. They are the ones who are not getting PPE. They are the ones who can’t afford to stay home. In “The African American Petri Dish,” my colleague Ronald Braithwaite of the Morehouse School of Medicine and I discuss how African Americans are in high-exposure petri dish positions since they are often the front-line workers, and this presents a greater challenge.

So we don’t want to get sidelined focusing on the historical issue of health disparities, which is important, but if you look back to move forward, the current conditions we face are worsening the problem.

Fabiola Cineas

What are your takeaways now, based on how you see the coronavirus impacting the black community? What does this all mean for the black community?

Reuben C. Warren

The takeaway is devastation, because we know better but we’re not doing better, especially when it comes to testing. Testing is important, but it has to be not only for those who show “signs” of infection. We know now that people can be asymptomatic. To test only those who have signs is a naïve-at-best, intentional-at-worst effort to not acknowledge the depth and breadth of the coronavirus.

We already know that without testing it is going to disproportionately impact people who are at greatest risk, particularly African Americans and Hispanic Americans. Then equally as important are the isolation and the follow-up. This is a challenge, and accessing health care is a challenge. Black people disproportionately lack access to health care and primary care doctors. So then there’s this fear of going to the emergency room. This problem is worsening.

Fabiola Cineas

Outside of Tuskegee, what else can you point to to explain black mistrust of the medical community? And how do you see it playing out now?

Reuben C. Warren

It’s rampant. You might have heard the name J. Marion Sims, who is the “father of gynecology.” In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Sims tested vascular surgical techniques on enslaved black women — without anesthesia. He tested and retested them like this — and he’s the “father of gynecology”! He even published an article on these women.

There is a study from the early 2000s called “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care” where scientists looked at health care delivery and found that there was a disparate difference between the quality of care given to blacks and whites, even with the same economic status.

Then there’s the other classic, the 1985 “Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health.” This documents 60,000 excess deaths in the black population each year, “excess deaths” being using the death rate of the white population and comparing it to the death rate of the black population. There were 60,000 excess deaths each year due to six causes: cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, unintentional injuries, and infant mortality. And then in 1992, HIV and AIDS became the seventh. Then in 2002, David Satcher, the former surgeon general, did this analysis again and found that the excess deaths had increased to about 83,000.

So, today, the problem is clear. We need not revisit the problem again and again. Let us move toward doing what we know can ameliorate the problem. Let’s prioritize resources based upon need, not based upon politics. Consistently, the black population demonstrates the greatest disparity; therefore, it’s where the greatest resources are to be committed. But it’s not happening.

Fabiola Cineas

Georgia, a state where black people are disproportionately infected with and dying from Covid-19, has reopened during the pandemic despite expert advice that says stay-at-home measures should remain in place. What parallels do you see between this move and what has happened historically?

Reuben C. Warren

The vulnerability is clear. There’s a 1974 book by [economist] Victor R. Fuchs titled Who Shall Live? Health, Economics, and Social Choice. Like the title of the book, we have to decide who shall live. The historical record and the current practices suggest something very scary. Some folks who happen to be in power will have to decide who shall live.

There’s a notion called herd immunity, and that’s what they’re doing in Sweden. There are people going about their normal day-to-day with no social distancing. They’ve just accepted that a certain percentage of the population is going to die. But Sweden has a very different demographic than the United States. Those who are at greatest risk here are people of color. They are the most vulnerable to live and also the most likely to die, regardless of income, education. Across any demographic, the black population disproportionately suffers.

Right now, the messengers don’t look like those who need to hear the message.

The country asks for trust, and I would argue that until those leaders at whatever level demonstrate trustworthiness, trust will not be forthcoming. Shift the paradigm from those who are most vulnerable to those who have the most power and authority. Trustworthiness is the framework, not trust.

Fabiola Cineas

Is it ethical for these states to open up now during the pandemic?

Reuben C. Warren

No. I think it is a priority of health over economics. The decision is that clear — there’s no either/or. Health is the priority. Public health ethics is based upon the population as opposed to the individuals, and to resolve public health issues, we look to three constructs.

The first is community engagement. The second construct is not benevolence but beneficence — what are your intentions and what are you going to do? The third is social justice, doing what’s in the best interest of the population at the greatest risk. It’s not the whole population, as that would instead be the utilitarian principle or the happiness principle for the greatest good but at the expense of those who are suffering.

That utilitarian principle does not work in a diverse population, particularly when subsets of the population have been historically disadvantaged and abused. And bioethics does not work in this construct. It is a valuable principle, framework, and concept, but it doesn’t work in population-based challenges. This is a public health challenge, and the response and the resolve have to be embedded in public health ethics.

Fabiola Cineas

Thinking about what ultimately happened to the men in the PHS syphilis study at Tuskegee, what are your final thoughts about how the coronavirus is playing out in black communities today?

Reuben C. Warren

Yes, some of the men died from diseases and conditions associated with syphilis. Some survived. And some suffered throughout the process — from the disease, if you will, but also from the horror, the embarrassment, the disgrace. And not only the men but also the families. A granddaughter of one of the men said she was called the syphilis kid in school. The emotional trauma is yet to be fully realized. There’s community trauma, and we have to acknowledge they’re moving from blame and shame to honor and glory. That’s a journey. We’re on the way, but we’re not fully there yet.

I see the same thing now, in focusing on the disease but not focusing on the condition and the vulnerability as a result of the disease. We don’t know enough, but we know enough to do better. To not test broader is unconscionable. If we don’t recognize and acknowledge history and its truth, then we are bound to repeat it.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.