Chris Thorpe wants you to think about nuclear weapons because they could kill you, and he wants you to talk about them more often. A theater writer from Manchester, England, with a long record of award-winning creative work on themes of nationality, identity, and borders, Thorpe’s newest project is a play intended to weave the total destructiveness of nuclear weapons into the fabric of everyday conversation.

I interviewed Thorpe on the sidelines of the historic first Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Vienna last week. He was there to gather inspiration for his show, which opens in December.

Titled A Family Business, the show focuses on the human story of the struggle for nuclear disarmament. The show reveals the ordinariness of the decision makers who manage nuclear risks, and of the diplomats and activists working for disarmament. It portrays the ordinary relationships, the friendships and the antagonism, that exist between them, and demonstrates that the human dynamics between these “experts” are the same that underpin the everyday lives of ordinary people.

The play is audience engagement first and performance second. Audience members will interact with those on stage, with each other, and will even take over part of the show. Far from being preachy, this self-made experience is designed to leave spectators with a quiet awareness of the acute threat that nuclear weapons pose—and to allow them to be scared by the scientific truths about nuclear war, without feeling ashamed for their perhaps limited knowledge on the topic.

Thorpe’s show will localize nuclear weapons issues, pulling them out of an untouchable realm run by far-away, suited officials, and importantly, asking what humanity an ordinary person must possess to make the right decisions on behalf of huge numbers of other ordinary people. It’s a refreshing deviation from the usual forms of engagement on nuclear issues—conferences, papers, panel discussions—and a long overdue examination of decision making around nuclear weapons through a cultural lens. Thorpe and I talked about the power of theater to transform people, and about what it will take to abolish nuclear weapons.

Louis Reitmann: Your play wants audiences to connect with the threat of nuclear weapons and the goal of disarmament on an emotional basis. Before we talk about the play, can you tell me about any moments during the Meeting of States Parties that gave you an emotional response like this?

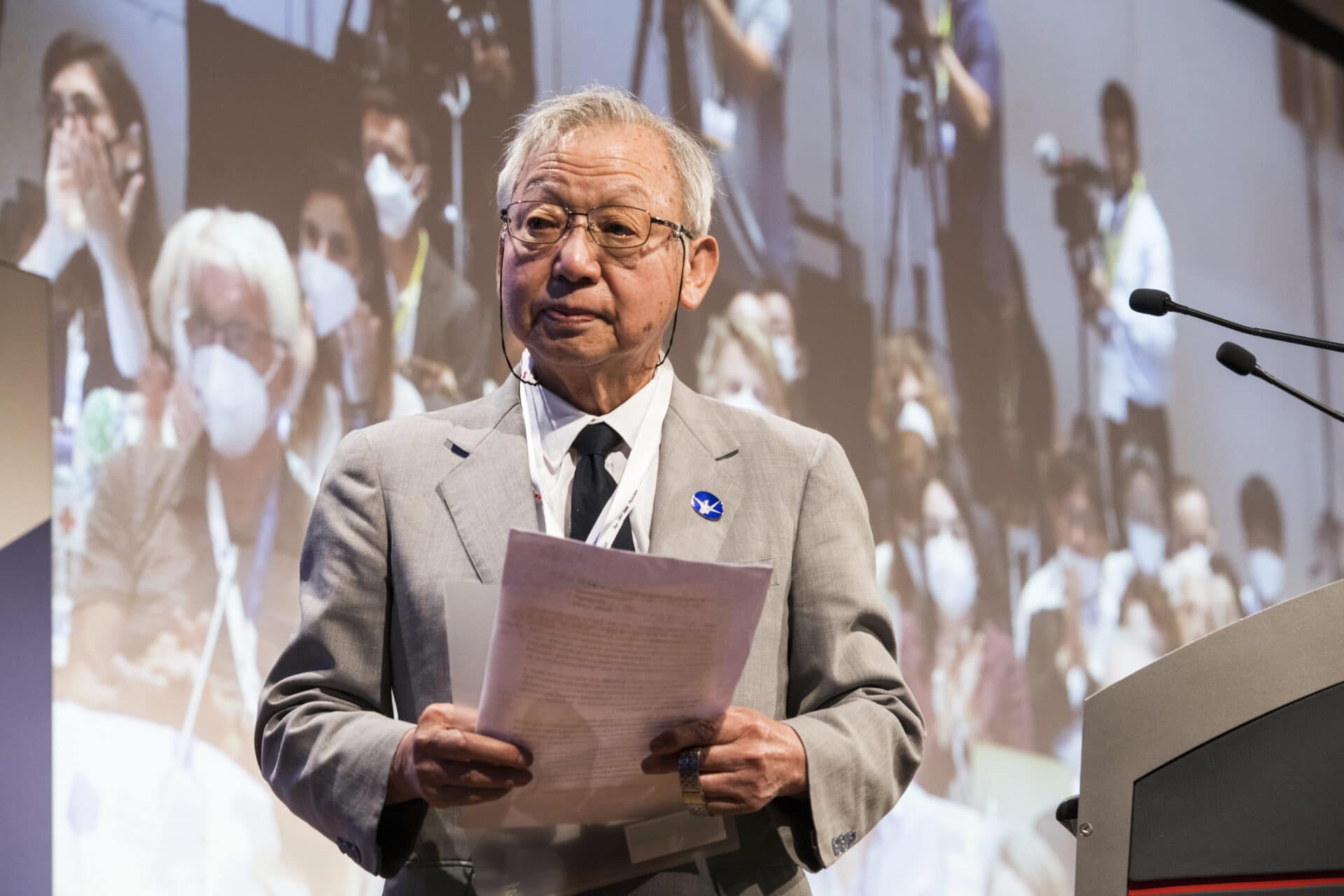

Chris Thorpe: An extremely impactful moment for me was when the chair of the hibakusha, the atomic bomb survivors in Japan, shook my hand at an event. It was like touching history. It triggered a lot of emotions in me, and I felt transformed by the experience. Holding out a hand that you can touch is a fitting metaphor for what theater does. I’m hoping for the audience to have the same kind of emotional explosion when they watch the show as I had in that moment. It’s about changing people’s awareness of nuclear weapons through a profound, emotional experience, rather than formal education.

Witnessing this kind of transformation in other people during the Meeting of States Parties has been emotional too. There’s something special about watching a ripple of realization wander through the audience when survivors of nuclear explosions share their stories. Afterward, people look at each other with new eyes. They become aware of each other and feel connected by the experience they just shared. They break out into smaller groups and eagerly discuss what just happened. In theater, it’s not just the story that’s effective, but the framework you can craft for people to talk. That’s why theater is a force multiplier for change. It’s about how we then use those experiences to build durable conversations and allow those conversations to coexist with our daily experience, rather than eclipse it.

Reitmann: Tell me about the emotions you want to evoke in the audience. And how would you respond to critics who might say you’re making people panic about nuclear weapons?

Thorpe: I want people to feel connected to each other. And because we’ll present the show in many countries and share the feedback from audiences in different places, I hope that the play will build a sense of solidarity between localities, connected in the experience they shared, in their awareness of the nuclear threat, and in their realization that those making decisions on nuclear weapons are ordinary. I also hope that the play can humanize these actors and illustrate the human relationships between them. I want audiences to normalize talking about nuclear weapons as a local issue.

One way to achieve this is by using NUKEMAP [a visualization tool created bynuclear historian Alex Wellerstein] to show the audience what a nuclear bomb exploding in the exact spot where they are watching the show would do. This is a powerful image and it demonstrates that, as far away as nuclear weapons can seem, their destructive power is laid over local, daily issues and interconnected with them.

However, the play isn’t about making people panic; it’s not told in a way that is terrifying. The content, the objective facts of what happens when a nuclear bomb explodes, is terrifying and it might scare people. Some, on the other hand, might disagree that surrendering nuclear weapons is a good idea and ask questions that are critical of the play. As a theater maker, I can’t ignore those. If you make art that only works if your audience reacts the way you want them to, you’ve made bad art. The play is about giving people the space to react to nuclear weapons in a way that is authentic to themselves. For many, it will be the first time they’re confronted with this issue.

There’s something more to that kind of criticism you mention. Some think it inappropriate to address the emotions connected to the threat of nuclear weapons. They see it as irrational or anti-rational. But a diplomat working on disarmament told me you can tell lies in a dispassionate, technical way and make an emotional case for the truth. We have only convinced ourselves that the more dispassionate something sounds, the more likely it is to be true. The emotional responses to the threats posed by nuclear weapons are real; ignoring them to pretend that nuclear weapons are safer than they are, or that the case for deterrence is somehow driven by logic, is what’s really irrational.

Reitmann: What motivated you to make the central aspect of the play about raising awareness?

Thorpe: I’m convinced that the lack of mass awareness of nuclear weapons or outrage over the dangers they pose, which are often lamented in the disarmament community, is not because ordinary people don’t care. Nuclear weapons are traditionally presented as an expert issue. They’re talked about in such technical terms that people without advanced knowledge don’t feel equipped or permitted to take part in the debate. They’re framed as a global issue, discussed only in spaces of high politics, as something without relevance in the daily lives of “ordinary people.”

A growing number of people have to deal with more direct concerns about their survival in unequal societies, that’s true—there are incredibly urgent issues in any community that can range from deeply personal to systemic issues of racial or economic justice. But just because people don’t have the same amount of time and resources to spend on this issue doesn’t mean that their level of engagement with the threat of nuclear weapons can’t be meaningful. If we can infuse the fabric of ordinary people’s lives with a quiet awareness of the immense dangers around nuclear weapons and the need for disarmament, that can shift the way entire countries think. That’s what the show wants to demonstrate—the powerful are ordinary, and the ordinary are powerful.

Reitmann: Let’s go back to the start. What sparked the idea for the play, and where did you go from there?

Thorpe: A Family Business is the final part in a series of three plays. The previous two explored cognitive biases in our thinking, and how they shape the collective stories we tell about ourselves, like our identities as nations. I wanted the third play to grapple with the question of how these collective stories interact on the global stage. I had just finished a show at a theater festival when a woman from the audience came up to me and wanted to know more about the project. Turns out I was speaking to the senior arms control adviser for the International Committee of the Red Cross, Véronique Christory. I was immediately fascinated by her work on nuclear disarmament, and I knew that I wanted to dedicate the third play to this issue. There is no better topic to demonstrate how high the stakes are for the global exchange between our collective stories in terms of our collective survival. Ever since, Véronique has been extremely generous in connecting me with experts and activists from the field, who have all helped develop the play. I’m very grateful for that.

Reitmann: Who do you most want to see the play? An obvious answer might be that you would like some world leaders, the people controlling nuclear arsenals, to be in the audience. Is that right?

Thorpe: What’s important about the show is that it’s designed to work for everyone everywhere, whether in a big venue in Paris or New York, or a small village pub in England. It’s a play that meets people where they are. I want it to speak to everyone, and anyone to feel spoken to.

The play doesn’t target anyone in particular; I’m not making it to lobby the influential. Those world leaders you mention would be welcome to watch the show, but as ordinary people, in the best sense of the word. Theater is an amazing art form because it can permanently transform an audience’s awareness and thinking on an issue through a collective experience, but this only works if every audience member feels ordinary, positively ordinary, ordinary together.

Equality and some anonymity between audience members is important for creating a safe space, free from embarrassment. That’s why we don’t ask audience members about their jobs or expertise. No one should feel inhibited to participate because there are “experts” present. We also need to turn off role expectations. If a decision maker participated in the show, I’d want them to react in a way that is authentic to themselves, not as is expected from the office they hold. Otherwise, they won’t be receptive to the long-term transformative experience the show aims to be.

Reitmann: Final question: You’ve referenced the power of ordinary people a lot. Do you believe civic activism will achieve the abolition of nuclear weapons, rather than negotiations between governments? After all, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty is in its 55th year of failing to bring about the elimination of nuclear weapons set out in Article VI. How much can formal, treaty-based meetings like the one we’re attending today really achieve?

Thorpe: I believe multilateral diplomacy is part of the mix of activities we need in order to achieve the disarmament goal. There are different kinds of pressure that can change leaders’ minds and force government policy. People can march and shout in huge masses; they can protest in ways that generate lots of visibility. These actions can be wildly successful, but what we need just as much are those actions that quietly, incrementally change the societal conversation surrounding decision makers, so that abolishing nuclear weapons will eventually become the obvious or the inevitable decision.

This is exactly what international meetings like this one, or projects like A Family Business can deliver. They’re about inching something onto the table, further and further, until it can no longer be ignored. If the play is trying to do anything, it is to normalize nuclear weapons, and how we could get rid of them, as an everyday topic of conversation. It starts in the theater, but hopefully, after the show, audience members can carry part of it back into their everyday world.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. A Family Business will premiere in Mainz, Germany, in December, followed by a United Kingdom tour in early 2023 and international shows beginning later that year. For information about how to collaborate with Thorpe or to book the show as part of its tour, contact producer Susan Wareham.