Halfway through the school year, Myrtis Bradsher found herself paying close attention to a little girl called Kizzy. She always looked sharp, with ribbons knotted to her ponytails and socks that matched every outfit. But it was the way she rushed to help other fourth-graders with classwork that really stood out. “She had so much knowledge,” the teacher recalled. “She knew something about everything.”

In 25 years at Oak Lane Elementary School in rural Hurdle Mills, N.C., Bradsher had not seen a child like her. Bradsher was one of a few black teachers, and Kizzy was a rare black student. At a parent-teacher conference, Bradsher pushed to give the girl the advantages she felt she deserved. “Look,” she recalled saying to her mother, Rhonda Brooks, “she’s so far above other children. We need to send her to a class for exceptional students. I need you to say we have your permission.”

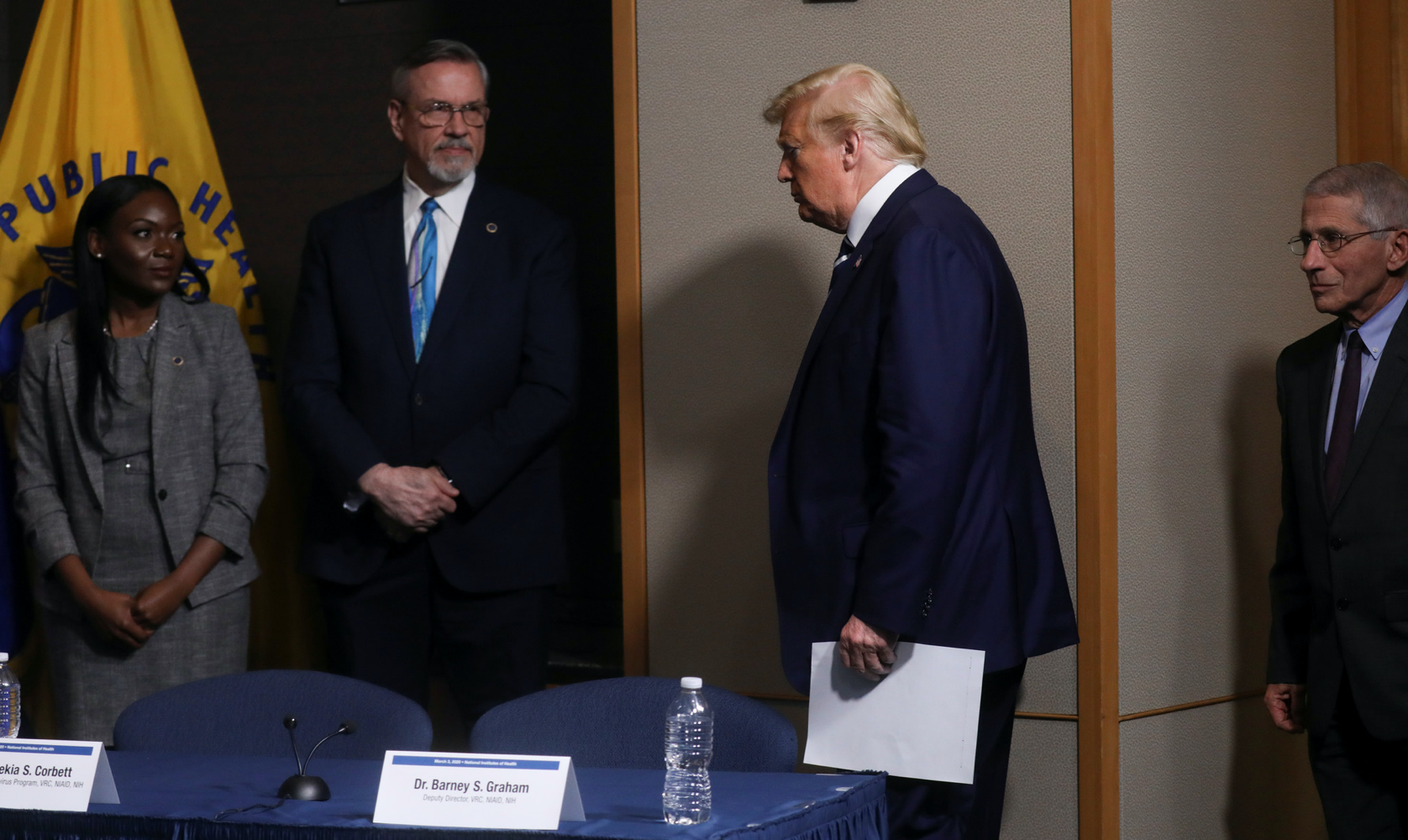

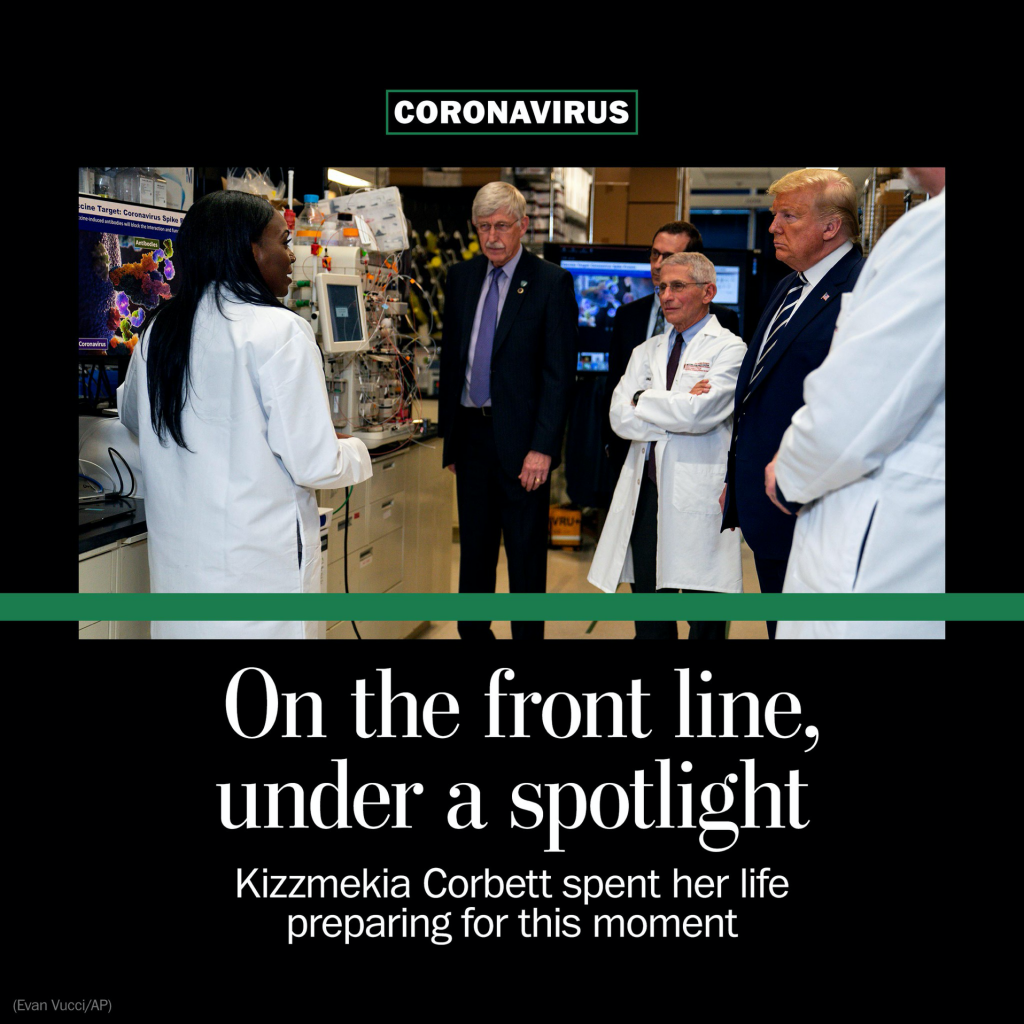

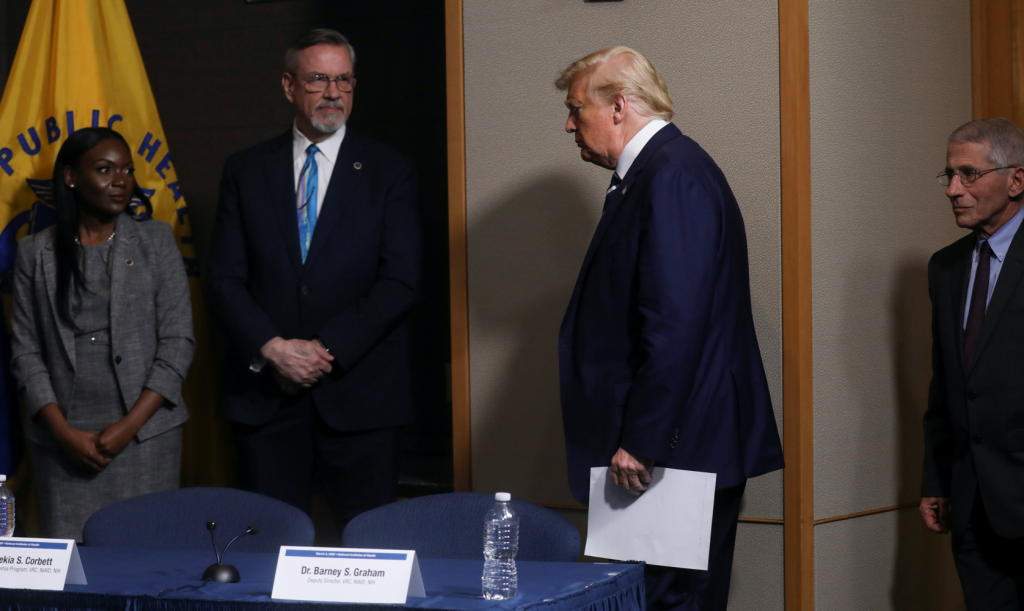

Bradsher’s recommendation put Kizzmekia Corbett on a path that ultimately led her to the National Institutes of Health, where she is heading the government’s search for a vaccine to end the coronavirus outbreak that has infected more than 1.3 million Americans, killed over 78,000 and devastated the economy.

Corbett, 34, is a long way from the tobacco and soybean farms that surround her old elementary school. The advanced reading and math classes at Oak Lane prepared her to become a high school math whiz. She was recommended for Project SEED, a program for gifted minorities that allowed her to study chemistry in labs at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as a 10th-grader. She accepted a scholarship for minority science students that paid her way through the University of Maryland Baltimore County and introduced her to NIH.

“I didn’t know Kizzy had gone that far until recently,” said Bradsher, now 72 and retired. “I figured she would, but I thought I probably would never hear about it.”

But her high perch comes with more visibility and added scrutiny.

On Feb. 27, Corbett posted a tweet that lamented the lack of diversity on President Trump’s coronavirus task force: “The task force is largely people (white men) he appointed to their positions as director of blah blah institute. They are indebted to serve him NOT the people.”

And, as public health officials were reporting startling data that showed that the virus was disproportionately killing African Americans, Corbett vented on Twitter. “I tweet for the people who will die when doctors has to choose who gets the last ventilator and ultimately … who lives,” she wrote March 29. When someone responded that the virus “is a way to get rid of us,” Corbett replied: “Some have gone as far to call it genocide. I plead the fifth.”

That triggered a response from Fox News host Tucker Carlson, who read several of Corbett’s tweets aloud on his show and questioned her “commitment to scientific inquiry and rational thought.” He accused Corbett of “spouting lunatic conspiracy theories.”

Two news organizations reported that the Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases where Corbett works, was investigating her tweets, but the agency said it had merely advised her of its social media guidelines.

Since the controversy, Corbett has scaled back her use of social media. She stopped appearing on television, and the NIAID declined to make her available to The Washington Post for an interview, saying a deluge of requests threatened to interfere with her work.

In an administration in which the president has had a tenuous relationship with his own scientists and experts, Corbett’s diminished visibility raised eyebrows. Her defenders say she was ridiculed for speaking the truth.

“I don’t think there’s anything she said that’s outlandish that goes against any type of code or standard,” said Robert Bullard, a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University in Houston.

“What I’ve seen parade across that stage in the task force, other than the surgeon general, are all white people,” said Bullard, who is black. “To look and see these horrific disproportionate numbers of African Americans dying of coronavirus vindicates her tweet. She knew this virus would be like a heat-seeking missile that would target the most vulnerable.”

African Americans make up 80 percent of people hospitalized for covid-19 in Georgia and, at one time, 72 percent of those who died of the disease in Chicago.

Oliver Brooks, president of the National Medical Association, an organization of black doctors, said Corbett was right to point out the dearth of black doctors and researchers on the White House team. “I’m sorry — we should be represented on the task force,” he said. “She was just stating a fact.”

Receive the most important pandemic developments in your inbox every day. All stories linked in the newsletter are free to access.

Corbett’s tweet about the ventilators reflects a long and painful history of disparity in medical care and health outcomes experienced by African Americans, Brooks said. One of the most notorious episodes, which sowed deep distrust in the medical establishment, took place from 1932 to 1972, when the U.S. Public Health Service allowed syphilis to progress in black men without their knowledge, denying them treatment with penicillin.

Long after that experiment ended, studies have shown white doctors spend more time with white patients than those who are black and prescribe different treatments. Life expectancy for African American men and women is shorter than for non-Hispanic whites, according to the federal government. And the death rate for African Americans is higher than for whites for a variety of ailments including stroke, heart disease, cancer, asthma, influenza, pneumonia and diabetes.

But Corbett’s tweet about genocide “concerns me a little bit,” Brooks said. “It’s subjective. I wouldn’t want to go there. I really don’t believe that. We’re dying at a higher rate but … that one just doesn’t fit.”

Still, if Corbett’s vaccine work is successful, none of that really matters, Brooks said. “I don’t care if she told me she doesn’t like my mama,” he said. “If she finds the vaccine, I’ll buy her lunch. I’d say I don’t like your politics, but I sure like your vaccine.”

Corbett’s team completed the first clinical trial for the development of a vaccine in early March. Working at a furious pace at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, the team hopes to have a vaccine by the middle of next year.

“She’s one of the hardest workers I know,” said Freeman Hrabowski, president of UMBC, where Corbett studied as an undergraduate from 2004 to 2008. “People don’t know how hard she works. She is an extraordinary human being with a passion for science and helping people.”

Corbett attended UMBC on a full ride as part of the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program, aimed at increasing diversity among future leaders in science, technology, engineering and related fields.

The program’s director, Keith Harmon, recalled how Corbett walked into the room with 25 other high-achieving minority students. “I remember a very energetic, really outgoing young person, a people person,” Harmon said. “You could just see in their eyes what it meant to be in this space with people who look like them and have their same drive and goals. It’s kind of like they’ve found their people.”

Corbett was intent on building on what she had learned each summer. Her first stop in 2005 was the Stony Brook School of Health Technology and Management in New York, where she studied under Gloria Viboud, an associate professor of medical molecular biology and program director of clinical laboratory sciences.

Viboud noticed what Bradsher saw in Corbett years before as she quickly mastered unfamiliar genetic cloning techniques and devoured background literature.

“She was always ahead of the other … students, completing an assigned poster and mock publication well before they were due,” Viboud wrote in a recommendation to the UNC doctoral program that she provided to The Post. “In 15 years of training undergraduate students, I must note that seeing a student as enthusiastic about research as Kizzy is extremely uncommon.”

In 2006, Corbett spent a year at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, where Susan Dorsey, a professor and chair of the Department of Pain and Translational Symptom Science, ran a lab that allowed students to perfect their work with wet chemicals.

“Some folks, it takes them a fair amount of time to learn the language and develop the skills,” Dorsey said. “She was very quick to thoroughly understand every single step, which for an undergraduate student is fairly remarkable. Every student realized … she would definitely be a superstar — sort of not an if but when.”

Four years later, she was in the doctorate program at UNC-Chapel Hill, spending her summers studying diseases such as dengue and coronavirus at what had become a familiar place, NIH.

“She worked on that for four or five years and was a kind of a leader,” said Ralph Baric, who served on Corbett’s thesis committee at UNC. “She actually had most of the pioneering data.” Her interests put her in position to assume a leadership role if a pandemic were to strike.

“It was a fortuitous move” that required “a little bit of luck, some foresight, and a need” for her type of expertise, Baric said.

At NIH, Corbett was not shy about her ambition. During a summer internship there, Barney Graham, who ran the Vaccine Research Center, asked her what she wanted to achieve in life.

“She said, ‘I want your job,’” Graham recalled, according to NBC News. “From the very beginning, she was really pretty bold in her aspirations.”

When Bradsher learned Corbett was leading the team that could save lives and restart the economy, she swelled with pride.

“I always thought she is going to do something one day,” she said. “She dotted i’s and crossed t’s. The best in my 30 years of teaching.”