Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

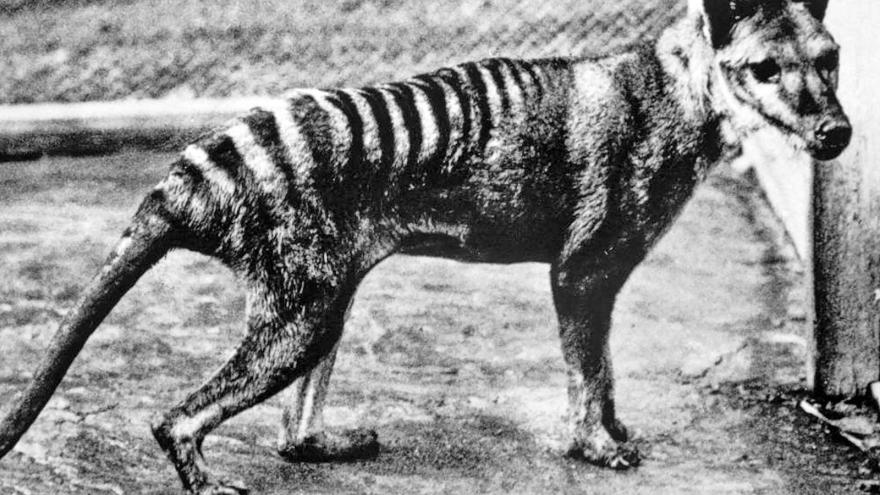

(CNN) — Almost 100 years after its extinction, the Tasmanian tiger may live once again. Scientists want to resurrect the striped carnivorous marsupial, officially known as a thylacine, which used to roam the Australian bush.

The ambitious project will harness advances in genetics, ancient DNA retrieval and artificial reproduction to bring back the animal.

“We would strongly advocate that first and foremost we need to protect our biodiversity from further extinctions, but unfortunately we are not seeing a slowing down in species loss,” said Andrew Pask, a professor at the University of Melbourne and head of its Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research Lab, who is leading the initiative.

“This technology offers a chance to correct this and could be applied in exceptional circumstances where cornerstone species have been lost,” he added.

The project is a collaboration with Colossal Biosciences, founded by tech entrepreneur Ben Lamm and Harvard Medical School geneticist George Church, who are working on an equally ambitious, if not bolder, $15 million project to bring back the woolly mammoth in an altered form.

About the size of a coyote, the thylacine disappeared about 2,000 years ago virtually everywhere except the Australian island of Tasmania. As the only marsupial apex predator that lived in modern times, it played a key role in its ecosystem, but that also made it unpopular with humans.

European settlers on the island in the 1800s blamed thylacines for livestock losses (although, in most cases, feral dogs and human habitat mismanagement were actually the culprits), and they hunted the shy, seminocturnal Tasmanian tigers to the point of extinction.

The last thylacine living in captivity, named Benjamin, died from exposure in 1936 at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. This monumental loss occurred shortly after thylacines had been granted protected status, but it was too late to save the species.

Genetic blueprint

The project involves several complicated steps that incorporate cutting-edge science and technology, such as gene editing and building artificial wombs.

First, the team will construct a detailed genome of the extinct animal and compare it with that of its closest living relative — a mouse-size carnivorous marsupial called the fat-tailed dunnart — to identify the differences.

“We then take living cells from our dunnart and edit their DNA every place where it differs from the thylacine. We are essentially engineering our dunnart cell to become a Tasmanian tiger cell,” Pask explained.

Once the team has successfully programmed a cell, Pask said stem cell and reproductive techniques involving dunnarts as surrogates would “turn that cell back into a living animal.”