A major Cy Twombly exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston shows how the modern artist painted under the spell of the ancients

Cy Twombly was a kind of artist-as-vandal. He seemed intent on defacing the grand tradition of Western art. But what he ended up expressing — almost compulsively confessing — was his ardent love for that tradition.

Twombly (1928-2011) was the most contradictory of 20th-century greats. On the one hand, he was a thoroughgoing modernist. With his clumsy, Brobdingnagian brushstrokes and penchant for twitchy finger painting, he was an heir to the performative abandon of Jackson Pollock. And just as Willem de Kooning had sought to undo his own facility by drawing with his eyes closed (and often drunk), Twombly practiced for hours at night in the dark, trying to unlearn how to draw. After seeing one of Twombly’s earliest shows, the critic Copeland Burg called his early paintings “revolting,” “truly shocking” and “the worst exhibition I ever saw in Chicago” — even as he grudgingly admired them.

You can’t get more modernist than that.

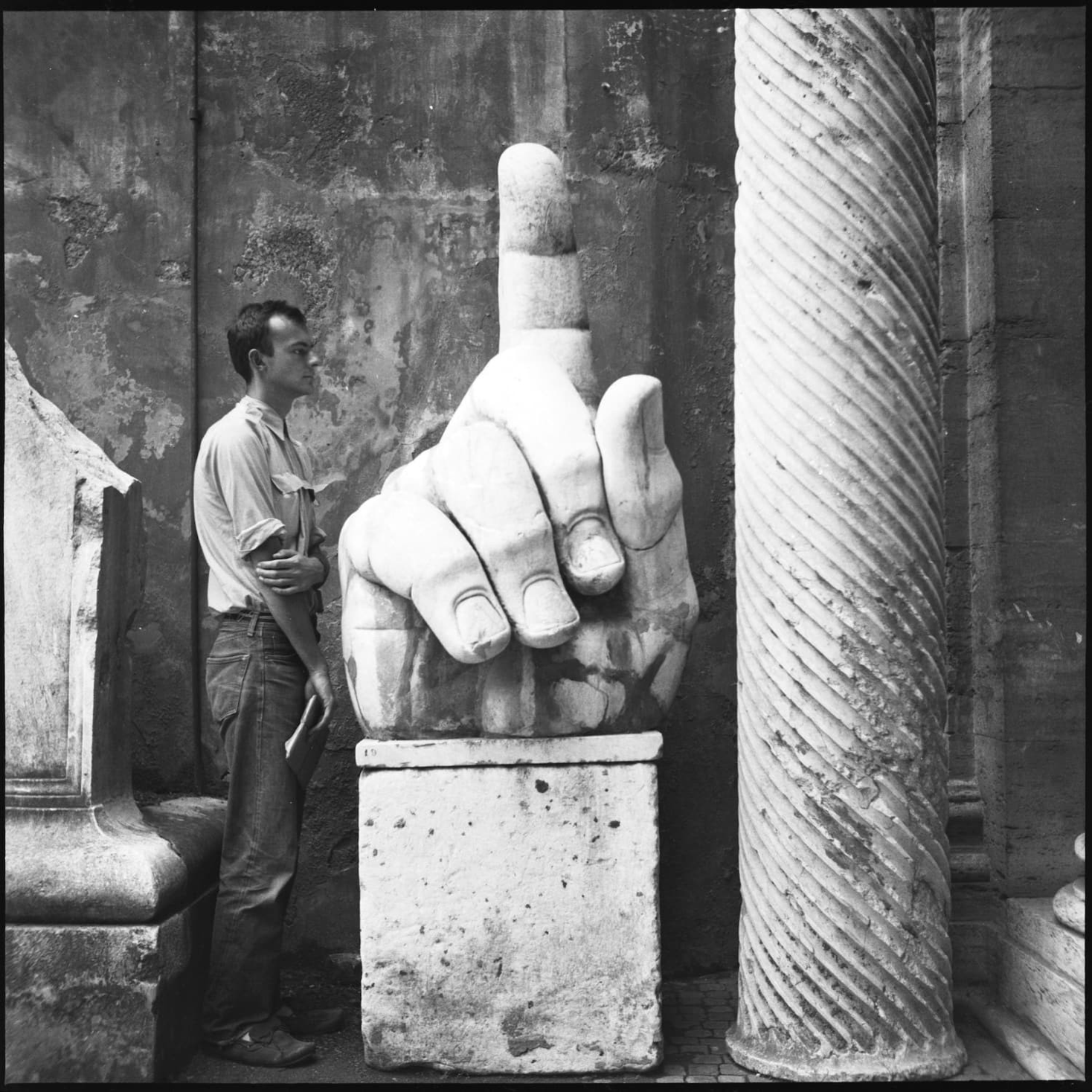

Yet there was another side to Twombly, expressed in his lifelong infatuation with the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome, as well as Egypt and the Near East. He lived in Italy for most of his life. His Romantic affinity for the remnants of antiquity was at once nonchalantly dilettantish and passionately committed. “What I am trying to establish,” he said, “is that Modern Art isn’t dislocated, but something with roots, tradition and continuity.”

“Cy Twombly: Making Past Present,” an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, does what no museum has previously attempted. Judiciously placing works by Twombly alongside classical statuary and other remnants from the ancient Mediterranean, the show reveals the nature and scope of his love of antiquity.

Just as Pollock’s drip paintings are material evidence of a Dionysian dance around a canvas spread on the floor, Twombly’s paintings can look like the aftermath of an orgiastic frenzy. They are almost embarrassingly intimate — full of smears and dribbles and scribbles. Yet you come upon them with a feeling of belatedness — as if you somehow missed the revelry and are left to survey the morning’s detritus in solitude.

There can be great emotion in this sensation, even arousal. Once, a Frenchwoman waited for a room to empty of other visitors in the glorious Cy Twombly Gallery on the grounds of the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. When a guard reentered, he found her standing naked in front of Twombly’s painted tribute to the Latin poet Catullus. “This painting makes me want to run naked,” she wrote in the guest book.

For centuries, people have felt similarly stimulated among the ruins of ancient Greece and Rome. The Vandals and Visigoths must have felt that way; Donatello and Brunelleschi no less. How can you outdo the Pantheon or the Parthenon? How do you match “The Iliad,” “The Aeneid?” There’s pathos in every attempt. “Every notion of progress is refuted by the existence of the Iliad,” wrote the Italian author Roberto Calasso. “The perfection of the first step makes any idea of progressive ascension ridiculous.”

Twombly, who was born in Lexington, Va., studied at Black Mountain College, where he mingled with a coterie of avant-gardists who would go on to revolutionize 20th-century aesthetics, among them artist Robert Rauschenberg, composer John Cage and poet Charles Olson. He moved to Rome in 1957, five years after having traveledto Italy and North Africa with Rauschenberg on a scholarship from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. On that first trip he had already started collecting antiquities at flea markets, nurturing the tendrils of sensibility that connected him with the ancient world.

Twombly’s attitude was often playful. He was aware of the vast distance separating him from antiquity. (But there can be vast distances between lovers in the same bed, too.) He was not a scholar. He never learned Greek or Latin, never became fluent in Italian. But he was a deep and passionate reader, both of the classics (in translation) and modern poetry by the likes of Rainer Maria Rilke, C.P. Cavafy and Wallace Stevens. He collected classical statuary (though not as a connoisseur; many of his things were copies). And he traveled widely.

The MFA show is magnificent. I feel like I’ve been waiting for it a long time. It takes Twombly out of the thin air of his contemporary reception, lately made giddy by the mere mention of his name, restoring weight and dimension to an uneven but always engrossing body of work. Organized by Christine Kondoleon, the museum’s outgoing chair of ancient Greece and Rome, the exhibition comes with a beautifully written catalogue offering informed commentary by authors including Kondoleon, Anne Carson and Mary Jacobus. There is also a small, linked exhibition of photographs by Sally Mann, Twombly’s friend, called “Sally Mann and Cy Twombly: Remembered Light.”

Twombly studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts straight out of high school. Boston has one of the world’s finest collections of classical art, and Twombly’s love of antiquity was fired by early encounters with the flotilla of Egyptian model boats, the ancient Iranian ornaments, and the Greek and Roman statuary in the museum across the street. This show, which opened at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles last year, comes at the end of a decade-long renovation of the MFA’s galleries for Greek and Roman art. So there is a sense of coming full circle.

I adore Twombly’s sculptures, which look like mysterious votive objects or ancient toys excavated from desert tombs. In fact, they are improvised, nailed-together constructions of wood, plaster, and sometimes plastic leaves or flowers, painted off-white to give them an aged patina. Slightly preposterous, they nevertheless have their own weird gravity. They are born, if you like, into belatedness.

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

Most of what we have salvaged from the classical past is in the form of fragments. Living in Italyamid the ruins of World War II, Twombly embraced the aesthetic of fragments and ruins. His association with composer John Cage, who embraced chance and silence, helped him see that the gaps and silences implied by ancient fragments may be as resonant as the objects themselves. His own works feel interconnected, as if each were a fragment from some larger whole. (“Myth, like language, gives all of itself in each of its fragments,” wrote Calasso.)

Under the spell of ancient tombstones and tablets, but also the “automatic writing” of the surrealists, Twombly took up the idea that the written word, legible or otherwise, could be thought of pictorially. His scrawled words resemble annotations, footnotes, commentaries scribbled in margins by drunken medieval monks. Single names — “Apollo,” “Venus,” “Sappho,” “Catullus” — evoke entire mythologies, whole bodies of literature.

In a large, horizontal painting titled “Orpheus,” a giant O takes up the left part of the canvas. The remaining letters, smudged and mostly erased, spread to the right and downward, like descending notes on a musical stave. There is a sense of resignation or fade-out in the script’s formation, as if the word were not worth completing, the gods having long since departed. But the letters’ placement also conjures Orpheus himself descending to the underworld to retrieve his beloved Eurydice.

In Rilke’s “Sonnets to Orpheus,” Orpheus is the figure who might yet unite the dead with the living through song. Twombly fell in love with Rilke’s work at Black Mountain, where he and Rauschenberg became amorously involved, and where Charles Olson was teaching about the connection between breath and spontaneity in poetry. One Greek word for “lover,” eispnelos, can also be translated as “he who breathes into another.” So the painting’s giant “O” becomes a sign for song or for the open mouth of a singer. Kondoleon has displayed “Orpheus” beside a broken theatrical mask from ancient Rome, its mouth open as if in song, the air of 20 centuries pouring through it.

Orpheus was transformed into a swan after his death. So Twombly’s “Orpheus” is connected with his many works addressing “Leda and the Swan,” including a superb 1962 canvas that contains a frenzy of marks in pencils, wax crayons and oil paint. Flashes of pink and red suggest spilled fluids and possibly violence. Once again, we arrive on the scene belatedly, in awe or dismay.

The exhibition’s final, incredibly poignant gallery contains works that touch on mortality. Among them is the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ “Synopsis of a Battle.” The painting’s fanning shapes, which resemble a battle diagram drawn hastily on a blackboard, look magnificent in front of “Thermopylae,” a cast bronze sculpture that resembles both a helmet pierced with arrows (with flowering tips) and, as Kondoleon points out, an ancient burial mound. “Thermopylae” salutes the Spartan soldiers who held off the Persians at that famous mountain pass, and nods at Cavafy’s poem of the same name.

Across the room, a tall ancient funerary monument shows a naked Greek athlete, young and muscular, carved in relief. Beside it is a Twombly collage invoking Adonis, whose name is a byword for masculine beauty. In the myth, Venus fell in love with Adonis before he was torn to pieces by a wild boar. (The subject was painted many times by Titian, whose sublime late works, full of shapeshifting potential and death awareness, tap into a sensibility often associated with Twombly’s.) Twombly’s collage includes words from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Adonais,” his elegy for John Keats, who had recently died in Rome at age 25.

Twombly returned annually to Virginia in his last 20 years. But he died, like Keats, in Rome, at age 83. What marks his work most powerfully, I believe, is his acute awareness of mortality. He understood that humans are probably unique among animals in having foreknowledge of their own death. This foreknowledge means that we live, like Orpheus, in two realms, and it drives us to create the illusion that our lives have plots and meanings.

Yet Twombly grasped, I think, that life is plotless, that meaninglessness reigns — hence, perhaps, his urge to deface, to vandalize. In this, he was impeccably modern. But he wanted to live inside the contradiction of our double awareness, to dwell in the paradox. So he savored the exquisite beauty, playfulness and erotic heat both of the ancient past and of this, our one and only life. And through his own version of Orpheus’s song, he tried to draw them closer together.

Making Past Present: Cy Twombly Through May 7 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. mfa.org.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that Kate Nesin helped to organize the MFA show. Christine Kondoleon was the only curator. The story has been corrected.

Sebastian Smee is a Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic at The Washington Post and the author of “The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals and Breakthroughs in Modern Art.” He has worked at the Boston Globe, and in London and Sydney for the Daily Telegraph (U.K.), the Guardian, the Spectator, and the Sydney Morning Herald.