Long-standing policies and deeply rooted inequity — rather than a few “bad apples” in the criminal justice system — likely explain why Black defendants in certain parts of the country are more likely than others to be held in jail before trial, according to new research from the University of California, Berkeley.

But a relatively easy fix could be a key to undoing those racial disparities in pretrial detention.

“We rely on pretrial detention much too often, and there are huge human and fiscal costs,” said Jennifer Skeem, a professor of public policy and social welfare at UC Berkeley.

A pair of recently published papers suggest that an overreliance on a defendant’s criminal history has inflated the number of people sitting behind bars while their cases grind through the courts. Confronting the outsized role of such details in pretrial reports and improving how these reports are written could help identify who actually needs to remain in jail before trial and who can be safely released, said Skeem, a psychologist and lead author of the two new papers.

“We found that a majority of defendants who are detained are really at quite a low risk for either committing a new offense or failing to appear for their current one,” Skeem said.

The reports add depth to ongoing debates about the role and risks of pretrial detention, the nation’s reckoning with race in the criminal justice system, and the policy options for methodically and safely decreasing jail populations.

In research published this week in the journal Criminology and Public Policy,Skeem and her co-authors, Lina Montoya and Christopher Lowenkamp, examined probation officers’ decision-making in pretrial reports for 149,815 defendants across 81 federal court districts in the U.S. These reports contained troves of information about the defendants’ criminal histories, personal finances and social lives, among other things. They each also included a recommendation from the officer — usually upheld by a judge — about whether the defendant should be held in custody or released before trial.

Black defendants were 34% more likely to be recommended to be held behind bars until their cases were resolved, researchers found. Racial biases on the part of the officers writing the reports contributed to some of the disparities — particularly in cases that involved a lot of discretion, like when the defendants had little or no criminal record. However, focusing exclusively on things like implicit bias training “would leave most of the problem unaddressed,” Skeem said.

The vast majority of the racial disparity in detention recommendations operated through pretrial policies and guidelines, which are part of what Skeem called “institutionalized factors” that officers were instructed to consider. While those factors included things like the current offense and the person’s ties to the community, the biggest factor was the defendant’s criminal history.

Approximately 70% of the racial disparities observed in pretrial detention recommendations were traced to just that one policy-relevant consideration.

“By far,” Skeem said, “the pathway through which most of those racial disparities were operating was criminal history alone.”

Why criminal history matters … to a point

Little is off the table in an officer’s far-ranging pretrial risk assessment interview. The officer asks about the defendant’s residence, family ties, foreign connections, employment status, education, finances, physical and mental health, substance abuse and gambling. Their report also details the person’s criminal history — from assault cases to traffic tickets.

To be sure, criminal histories are heavily emphasized because they are often the best predictor for future offenses, Skeem said. But a person’s record often becomes a laundry list of offenses that may have nothing to do with the most recent allegation — a speeding ticket from 10 years ago, for example, as a sign of a person’s chances of committing a drug offense today. Additionally, offenses are often featured repeatedly in the same pretrial risk report, amounting to double or triple counting of the same incident.

This kitchen-sink approach to risk disproportionately affects Black defendants, Skeem said.

“Criminal history belongs in a report and must be acknowledged, but ideally, the focus would be on a few predictive factors that are presented once,” Skeem said. “This is a heavily policy-related story. Changing some of the policy guidance and tools for pretrial decision-making will provide the greatest gains in reducing disparities.”

That’s why Skeem and her colleagues said they advocate for “corralling criminal history.”

This could entail using a narrow set of past offenses that are most predictive of committing new crimes. It also requires acknowledging the “shelf life” of a past offense, which might not be remotely helpful in understanding the defendant’s risk today. And on a technical level, reining in how often such a history can be referenced in a report could ensure it isn’t overused, Skeem said.

“Trying to corral criminal history — to adopt a tighter definition — would probably make a bigger dent in disparities than tackling implicit or personal biases,” Skeem said, adding that it would also improve the likelihood of more accurately achieving the original goal of meaningfully predicting risk.

Pretrial racial disparities vary across the U.S.

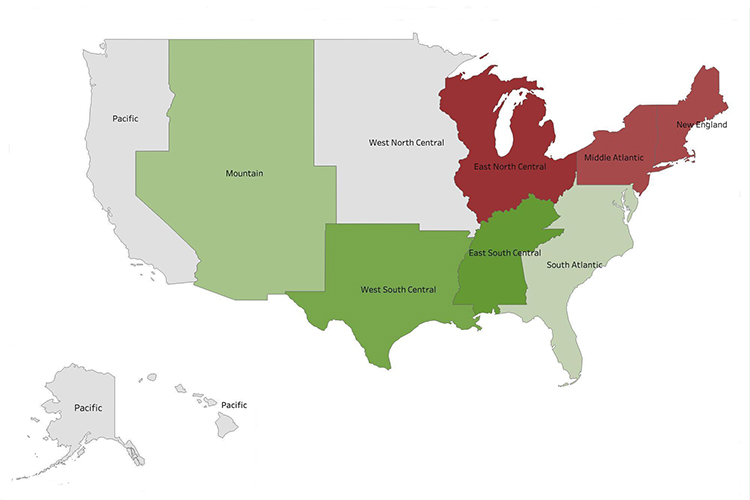

The research team’s second recent paper, published in the journal Federal Probation, shows significant geographical variation between the Black and white pretrial disparities. The greatest disparities in the U.S. appeared in districts in the Northeast and the Midwest.

Given the progressive politics of the region, that might seem counterintuitive, Skeem said.

“It’s not the stereotypical places that you would expect to find the greatest disparities,” she said. “It’s not in the South or in areas that we are accustomed to thinking of as associated with racism.”

The true explanation is likely that broader structural inequality and deep-seated economic vulnerability are closely linked with involvement in the criminal justice system.

“In places where pretrial disparities are bundled with broader indices of racialized social inequality,” the researchers wrote, “it is essential to also address ‘root causes’ of involvement in crime that include socioeconomic disadvantage, educational and job opportunities, and more.”

In other words, they said, pretrial reform cannot alone address any “true differences in risk that lie further upstream.”

An innovative data set and collaboration

Finding safe and smart ways to decrease the number of people held in custody awaiting their cases’ resolution is more than just a passion project for advocates and progressives.

Jails are among the most expensive line items that taxpayers finance every year. Severe staffing shortages are common, as are dangerous — sometimes unconstitutional — conditions. And pretrial detention is profoundly disruptive and has been shown to cause ripple effects that can cost legally innocent people their jobs, paychecks and housing.

In theory, county jails are a gateway to a similar system of justice for defendants. In effect, however, they’re like hundreds of silos operating with their own rules across the country — a reality that makes meaningful research on incarceration data a herculean task.

That’s what makes Skeem’s latest projects especially noteworthy.

Skeem partnered with a team at the U.S. Administrative Office of the Courts, where in-house researchers have worked for years to capture reliable criminal justice data from federal court districts across the country. Federal offenders are held in local jails run by the county, but their cases are managed through a nationwide database. That brings a degree of consistency to the federal pretrial detention reports, whether they’re being conducted in California or Alabama.

A committee within the federal courts’ Probation and Pretrial Services System had been working to better address disparities, and it tapped Skeem and Montoya, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to help analyze the data.

“It’s rare to be able to work with an agency that has such complete and relatively clean data,” Skeem said. “We’re the only outside researchers that got to work with that group from the beginning to figure out what the best questions would be to ask of their really rich data.”

Lowenkamp, a researcher who works with the courts, also helped lead the project.

The research team was also able to leverage the institutional knowledge from officers and chiefs to inform how policies might be changed — all the way down to how pretrial risk assessment and report instructions could be modified to create a more equitable outcome. The co-authors believe theirs is the first study to map the personal and institutional influences on racial disparities in officers’ recommendations for pretrial detention in the U.S. justice system.

Combined, Skeem said the reports can help signal a path forward for finding responsible ways to safely overhaul pretrial detention. Pretrial reform alone won’t solve the problem, but using increasingly sophisticated methods, early research shows, can help move in that direction.

“The priority goal,” the researchers wrote, “is to first do less harm by eliminating unnecessary detention.”