Enric Sala—marine ecologist, conservationist, and ocean advocate—is standing under a life-size replica of a Northern Atlantic Right Whale at the natural history museum in Washington, D.C., and the air outside is smudged with wildfire smokedrifting down from Canada. It’s not surprising that Sala wants to talk about the smoke, or about whales. Their poop, however, is an unexpected twist. According to Sala, whale excrement, or, more precisely, the lack of it, has a role to play in the choking miasma that has forced my interview with one of the world’s foremost ocean explorers indoors instead of out on a boat.

Therapists Raise Red Flags About Using ‘Therapy Speak’ Online

Watch More

It may seem like a stretch, the kind that relegates environmentalists deep into woo-woo territory, but as our conversation unfolds, it starts making sense. Whale poop fertilizes ocean plankton. The plankton reproduces rapidly, absorbing carbon dioxide as it photosynthesizes sunlight. Eventually it sinks to the seafloor, trapping the planet-warming gas in layers of sediment. Fewer whales means less plankton sequestering CO, leaving more in the atmosphere. That means more of the heat driving the wildfires that have smoked out much of North America.

“Suddenly, we’re seeing that the impacts of climate change are not something that is going to be suffered by somebody else,” says Sala. “It’s here.” And so it is, in the wildfires, heat waves, and floods that have made the weather of summer 2023 some of the most extreme on record. Greater biodiversity, whether it is found in the ocean’s whale populations or the old-growth forests that also store carbon, can help mitigate the effect of burning fossil fuels much more cheaply than any new technology, he says. “The more nature we have, the more nature will be able to absorb our impacts.”

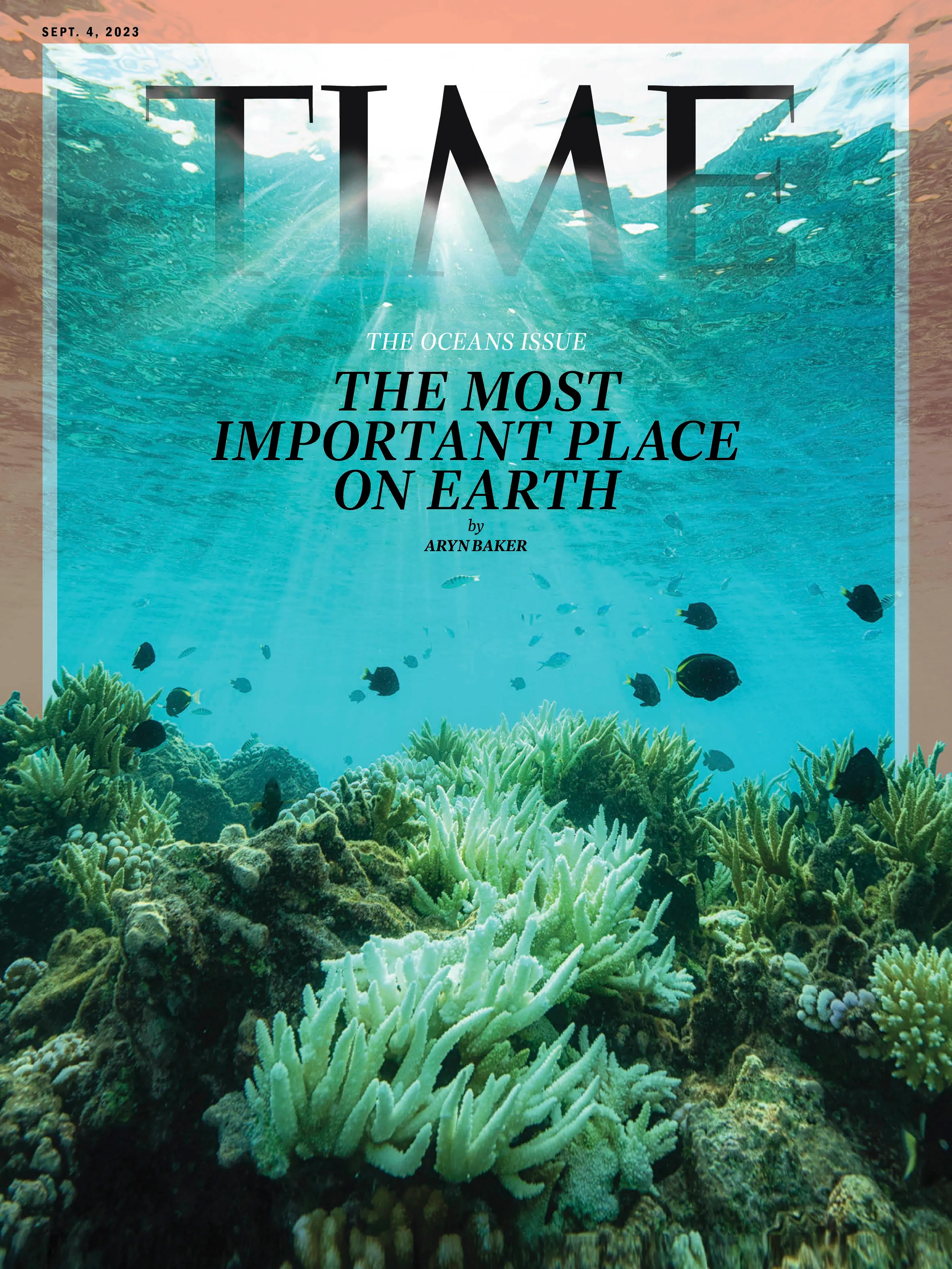

Photograph by Cristina Mittermeier—SeaLegacy

Sala’s links between healthy ocean ecosystems and human benefits like carbon sequestration are backed up by science that he has either committed to memory or conducted himself. But it’s the ability to break scientific complexity into simple concepts that even landlubbers can comprehend that makes him so effective as an ocean advocate, helping rally global governments to commit to protecting 30% of their coastlines and ocean territories by 2030. His Pristine Seas project, sponsored by the National Geographic Society, has identified dozens of the ocean’s most biodiverse hot spots in an effort to call for their protection. Already he has managed to get 2.5 million sq. mi. (6.5 million sq km) of coastline and ocean set aside in 26 marine protected areas (MPAs)—an expanse twice the size of India—where fishing, dumping, mining, and other destructive industries are prohibited.

On May 24, Pristine Seas’ scientific-research ship the E/V Argo lifted anchor for its most ambitious undertaking yet: a five-year expedition to the remote tropical Pacific, where Sala plans not only to chart the world’s biggest ocean from its unplumbed depths to its more familiar shores, but also to document the complex links between marine ecosystems and the lives they support on land in order to build a case for their conservation.

The ocean needs that help more than ever. The morning of our meeting, the European climate-monitoring agency reported that May 2023 had seen the highest ocean temperatures on record, increasing ocean acidity, weakening marine ecosystems, and forcing coral polyps to expel their colorful symbiotic zooxanthellae algae in a near-death phenomenon called bleaching. By the end of July, waters off the coast of Florida had reached Jacuzzi temperatures, and volunteers were racing to transfer fragile coral sprouts to indoor aquariums before they cooked to death. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), about 40% of the world’s oceans are currently experiencing a marine heat wave, with as much as 50% forecast for September.

The ocean has already absorbed more than 90% of the planet’s greenhouse-gas-fueled warming, explains Sala, “but it will not be able to absorb our impacts for much longer without serious consequences.”