June 14, 2021

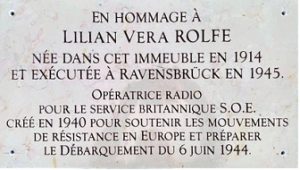

(NOTE: 19th May 2023 – a plaque commemorating Lilian Rolfe was officially unveiled at the former Rolfe family home at 32 Avenue Duquesnes, Paris 75007 by the Deputy Mayor of Paris, the British High Commissioner, Deputy Mayor of the 7th Arr of Paris & Mayor of Nargis. In attendance was the British Air Attaché and representatives of AFHG/GPFA; Royal British Legion; RAFA and members of the Rolfe family).

Lilian Vera Rolfe – Beyond Courage

(Vers en français cliquez ici)

Secret agents played a significant part in liberating Europe. Many suffered terrible consequences. This is the story of just one.

PM Winston Churchill inspects bomb damage during the Blitz in London – 1940

Introduction

On 16th July 1940, as Luftwaffe bombers stepped up their attacks and Britain prepared their defences against the threatened invasion, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, anxious to hit back and show that Britain was not defeated, ordered the establishment of a special covert unit to infiltrate occupied territories and “set Europe ablaze!”

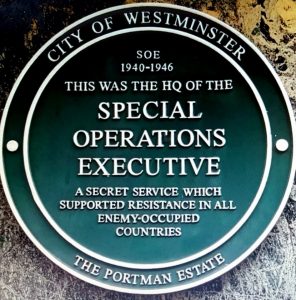

The highly secret Special Operations Executive (SOE) was formed on 22nd July 1940: to undertake reconnaissance, espionage and sabotage operations in occupied Europe. Eventually employing over 20,000 people of which over 3,000 were women, the first SOE agent was parachuted into Occupied France on the night of 5/6 May 1941.

64 Baker Street, London NW1 – headquarters of SOE from 31 October 1940. Eventually it expanded into most of the western side of the street. Also known for its fictional link to Sherlock Holmes, “Baker Street” became the euphemistic name of SOE.

Within SOE, clandestine operations in France were mainly organised by F (French) Section which operated towards British policy and aims, and also by RF (République Française) Section linked to General de Gaulle’s Free French organisation. In addition, the EU/P Section, dealt with the Polish exiles in France and the DF Section organised escape routes for SOE agents and their helpers, and AMF Section despatched agents from Algeria after the invasion of North Africa.

SOE conducted hundreds of highly effective sabotage and covert actions to disrupt enemy activity and were especially important in their operations disrupting enemy reaction to the Allied invasion on 6th June 1944. From D-Day, the SOE also played an important role in the many three-man, inter-Allied ‘Jedburgh’ teams that were dropped, in uniform, into France as part of “Operation Jedburgh” – an overt operation working alongside the French Resistance.

By the very nature of an organisation of this kind, its operatives could be ruthlessly tortured or executed if caught, and their members would be amongst the most courageous and bravest individuals of WW2.

Wireless operators were especially vulnerable to the radio signal search techniques of the Abwehr and Gestapo, giving the average “lifetime” of an SOE agent radio operator of just 6 weeks at one point in the war. One such agent was Lilian Rolfe, and this year a new plaque has been installed in her honour in Paris.

Lilian Vera Rolfe was one of twin daughters born on 26 April 1914 in Paris where her British father, George S. B. Rolfe, worked as a chartered accountant and the family lived at 32 Avenue Duquesne.

Her mother, Alexandra (née Stern), was originally from Russia, but Lilian and her sister, Helen, took British nationality.

Fluent in both English and French, she was educated in Paris from 1922 to 1931 at the private catholic school, the Cours Dupanloup in the Boulogne-sur-Seine district, where she took the first part of her baccalauréat in sciences and languages. An accomplished violin player, she then spent three years at the prestigious Conservatoire de Musique Russe in the very centre of Paris, looking out over the Seine towards the Eiffel Tower, combining it with a two-year business secretarial course, from 1932 to 1934. Lilian finished her schooling in Brazil when her family moved to Rio de Janeiro, living in the Avenida Niemeyer, the coastal road in the southern suburbs overlooking the São Conrado Bay.

When war broke out, Lillian began working in the Press Department of the British Embassy in Rio de Janeiro, where she is reported to have helped observe German shipping movements in the harbour.

In January 1942 she was successful in gaining a position of Secretary in the Canadian Legation, but as public opinion in Brazil became increasingly pro-Allied (Brazil formally declared war on Germany in August 1942), Lilian determined to take a more active role in helping her mother country in its fight to free the country of her birth.

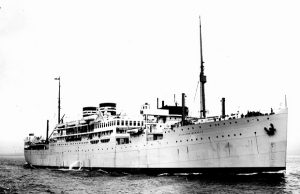

S.S. Highland Brigade

Lilian left for Britain on the “SS Highland Brigade”, a passenger ship of the Royal Mail Lines that had been chartered mainly to carry some 605 volunteers for the British cause from South American countries. It sailed from Rio de Janeiro in February 1943 and Lilian left her family behind with the aim of joining the WAAF or WRNS in Britain. She suffered from sea-sickness on the journey, but took her part in anti-submarine watches which were the duties of the young women on board.

The voyage proved to be a memorable one for the “SS Highland Brigade”, with echoes of the fate of its predecessor of the same name, sunk by a German submarine on a run to South America in 1918. After a stop at Bermuda before the blacked-out run across the north Atlantic, the ship was hit by what was believed to have been a mine (or it may simply have just been damaged by extremely bad weather – the passengers were not told!) and for a while Lilian and the other passengers were mustered at lifeboat stations, expecting to have to abandon ship. Instead it headed for New York and repairs. She eventually arrived in Liverpool on 12 April 1943 and wasted no time in volunteering for the WAAF, being accepted as an Aircraftwoman 2nd Class on 16 April 1943, with the service number 2149745. She was sent for her initial training at RAF Innsworth in Gloucestershire, where she succumbed to chickenpox and had to spend some time in quarantine.

Womens Auxilliary Air Force wartime recruitment poster

After her recovery, she progressed for training as a Wireless Operator in Blackpool and then went on to RAF Bicester in Oxfordshire where life was enlivened by it being an active training airfield for medium bombers.

In December 1943, Lilian arranged to meet in London with a good friend, Cynthia Sadler, whom she had known in Brazil since childhood and who had also come to Britain and had joined the WAAF. Swearing her friend to secrecy, Lilian revealed she had volunteered and had been accepted the previous month for ‘special duties’, that she was now undergoing training and expecting a commission. She gave her friend a recent photograph of herself in uniform and several letters to be posted at intervals to her parents in Brazil as cover. Records confirm that she first attended STS 7 at Winterfold, Cranleigh, Surrey for her Students’ Assessment Board in December 1943. She achieved a ‘C’ rating overall, and an impressive intelligence score of 8 with the comments:

‘A highly intelligent, sensitive girl of considerable capacity and accomplishments. She is shy and reticent and needs encouragement to get the best out of her. Calm and deliberate, slow and cautious. Very painstaking and conscientious and readily learns from her mistakes. Imbued with high ideals and very anxious to turn her training to good account. Very well suited for W/T work. It is very important that she should have complete confidence in the person she is to work for, as she is a rather dependent person and needs the support of a strong and stable character’.

Special Operations Executive Establishment – STS 4/7: Winterfold House

Cleared to continue for Group A paramilitary training, Lillian reported in mid-December to STS 23a at Meoble Lodge, Morar, in Scotland and then went on to STS 22 at Rhubana Lodge, Morar.

On 2 January 1944 Lilian spent a few days on a preliminary Wireless/Telegraphy course at STS 52, Thame Park, Oxfordshire, before joining a parachute course. Housed at STS 51a, Dunham House, Altrincham for her training at STS 51 at RAF Ringway, Manchester, just five miles away. But to her disappointment, a physical check-up led the Medical Officer to declare her temporarily unfit for jumping. On 9 January, Lilian was therefore posted back to undertake the full W/T course at Thame Park, including familiarising herself with the sets used by SOE and developing her coding skills.

As a desperately-needed W/T operator who could speak fluent French, she was sent on active service as quickly as possible in the next ‘moon period’ after the end of March 1944. Prior to the completion of her training Lilian received two promotions. As benefitted an existing WAAF, she was granted an honorary WAAF commission as an Assistant Section Officer with effect from 1 April 1944 and with the new service number 9907. But at the same time, Lilian was enrolled in the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) as an Ensign, in order to sidestep the ruling that women members of the armed forces could not serve in the front line.

Parachute training from Whitley bombers (two Lysanders also visible) – RAF Ringway, Manchester

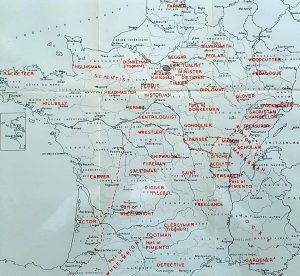

Lilian’s role was to act as W/T operator to a new SOE “circuit” called HISTORIAN that would operate in the Orléans area and concentrate on railway targets. Several useful contacts among the local railway workers had been made on an earlier mission by Philippe de Vomécourt (VENTRILOQUIST/Antoine), and the circuit was to be led by Captain George Wilkinson (HISTORIAN/Etienne), supported by Lieutenant André Studler (SYLVAIN/André) as his deputy. Studler was a French-born agent of the American OSS, seconded to F Section.

F Section Circuits in France active in 1944 – note “Ventriloquist” and “Historian”

It had been planned that Wilkinson would go to France first, as he had lived in Orléans, knew the area well and could make preparations for the arrival of his two subordinates. But due to bad weather he did not parachute until the night of 5/6 April 1944, the same night that Lilian and Studler were being delivered in a double Lysander aircraft operation, piloted by Flight Lieutenants Taylor and Turner in OPERATION UMPIRE. Lilian’s code name was RECLUSE, her field name was Nadine, her W/T traffic was to be BLOUSE and her false identity was in the name of Claudie Rodier.

Westland Lysander MkIIIA (Special Duties)

The two agents in the other aircraft were Philippe Liewer and Violette Szabó and they were met by Remy Clément east-south-east of Azay-sur-Cher (37) in the early hours of 6 April 1944.

Violette Reine Elizabeth Szabo, GC (“Louise” / “Corrinne”) 1921-1945

All went well and after waiting for the end of the curfew at 05:30. Lilian and Studler set off on bicycles which had been provided for them by Clément. Their aim was to first reach a contact in Châteauroux by cycling to Amboise and catching a train from there to Tours and then on to Châteauroux. This proved impossible when, on reaching Amboise at dawn, the two agents found there to be no trains running that day due, ironically, to sabotage of the lines. Deciding that staying locally in a hotel was too risky, they instead determined to cycle all the way to Châteauroux – a distance of some 100 kilometres. By evening of the same day they had only reached Loches, still 70 kilometres short of Châteauroux, but Lilian was exhausted. Unused to cycling, and tired from a lack of sleep on the night of her Lysander flight, she had not been able to maintain a good speed and there was no alternative but to risk staying the night in a hotel in Loches.

She and Studler did so without incident and the next morning caught a train for the remainder of their journey to Châteauroux, taking with them their bicycles, suitcases (including Lilian’s radio set) and three packages that they had brought with them from England. Successfully finding their designated contacts in Châteauroux, Lilian and Studler were then sent on, again by bicycle, to Saint Gaultier (36), another 30 kilometres to the south-west, where they met up with their circuit leader, George Wilkinson, who was then living in the town. Lilian was taken in by a local disabled woman, while Studler was sent to Neuvy-Saint-Sépulchre to await further orders.

Lilian (left) outside a “safe house” with the daughter of the owner of the property – 1944

The wait by Wilkinson, Studler and Lilian was necessary for contact to be made with Philippe de Vomécourt who was to introduce them to people in the Loiret region. Wilkinson arranged for Lilian to leave St. Gaultier during this enforced period of inactivity and to stay in a small hotel in Mézières-en-Brenne. Wilkinson continued to stay with Monsieur Dappe, a shopkeeper in St. Gaultier, and it was at his house that Lilian came to visit Wilkinson on or around 9 May 1944. Only an hour after they had left the house together, it was raided by the Germans and Dappe was arrested having been denounced by someone in the town’s Mairie for helping Allied agents.

St. Gaultier, central France, looking towards the Town Hall (Mairie) c.1947

Lilian then lodged at Saint-Hilaire with the owner of a garage, Henri Lejeune, his wife and the younger of his two daughters who was still at home, 16-year-old Marthe (‘Marty’). She stayed for little more than two weeks, but made a lasting impression on her hosts. Her cover story was that she was staying in Saint-Hilaire with friends in order to get away from the bombing in Paris which had upset her nerves and health. But with the Lejeunes, especially Marty, Lilian did not hide her real background and entertained them with descriptions of life in Brazil. She started transmitting messages to England, brought to her by courier from Henri Lejeune, and receiving replies – often throughout the night. As time permitted, she would also cycle about the area to note what the German forces were doing in the locality and, if considered important, report their activities back to England.

SOE portable “suitcase” radio Type III

One potential risk to Lilian was the presence in the village of a member of the Milice (the pro NAZI Vichy Militia), a man called Lagarde, whom Henri Lejeune warned her about upon arrival and advised that it might be prudent if Lilian were to quickly make friends with him. Lilian had little difficulty in doing so, charming him to such an extent that another local maquis group suspected her of consorting with the enemy, until Lejeune firmly ordered the nonsense to stop.

Lilian’s stay with the Lejeunes came to an end after a German Direction-Finding car stopped one day outside the house. George Wilkinson happened to be visiting Lilian and together they took up arms and awaited what they expected to be the inevitable assault on the house. But, perhaps because there was only one German in the car, it drove away. Not taking any chances, Wilkinson immediately arranged for Lilian to leave and she did so in the early hours of 6 June 1944, going to Égry (45) on 10 June where she was to support the activities of Pierre Charié, a wine merchant who was also the regional organiser of several maquis groups.

German (Abwehr) Radio detection vehicle.

Wilkinson was arrested on 26 June 1944 and Lilian radioed London on the 28th to relay the bad news and to ask for instructions for herself and Studler. London replied and approved Pierre Charié taking over the HISTORIAN circuit, which he did successfully, still aided by Lilian and Studler who now reported to him. In order to not stay in one place too long, as the Germans were continuing their radio direction finding activities, Charié ensured that Lilian moved every couple of days. She had done just that, to the home of two schoolteachers, Jeannette and Maurice Verdier, in the village of Nargis (45), some 15 kilometres north of Montargis, when her luck finally ran out.

The Commune of Nargis in the Loiret Department of North Central France

On 31 July 1944 a stranger appeared at the house, but having given the correct password, he was admitted – only to then trigger a Gestapo raid which netted Lilian, her bodyguard, François Bruneau, and the Verdiers. Bruneau, though handcuffed, managed to escape and made his way on foot the 16 kilometres to Charié’s headquarters to warn him of the capture of Lilian and her radio set. Sadly, it was later realised that a strong maquis unit had been close at hand to the location where Lilian was arrested, but because of the security measures in place in Charié’s organisation, Bruneau did not know of its presence.

Two theories were later to emerge as to the cause of Lilian’s arrest. One is that she was simply caught through bad luck – that the Germans were looking for someone else and came upon Lilian and her W/T set by chance. The second, however, centres on the use of the Résistance password by the stranger who called at the house. The source of this password was later claimed to be Annick Boucher, alias Yvonne Tessier, and known locally as “la belle Annick” or “la grande blonde”. Nominally a member of the Résistance, Boucher was also allegedly the mistress of a number of German officers, including the second-in-command of the Orléans Gestapo. She is believed to have been in the pay of the German security services and it is this connection that led to suspicion falling on her for Lilian’s arrest. Boucher had been at a banquet attended by Lilian and arranged by the local maquisards on 29 July and many assumed that it was she who gave the Germans information of Lilian’s whereabouts in Nargis, together with the required password currently in use by the Maquis.

Charié wasted no time in planning a rescue attempt for the young woman he greatly admired and depended upon. Knowing that she had been first taken to Montargis, Charié anticipated that she would soon be transferred to captivity in Orléans, prior to being sent to Fresnes Prison and questioning in Paris. He therefore arranged for his maquisards to attack any enemy car leaving the Germans’ prison in Montargis. But the enemy, perhaps realising the importance of quickly trying to coerce Lilian into continuing radio transmissions to England, had already transferred her to Fresnes prison on the outskirts of Paris, from where it can be presumed she was taken for interrogation at the avenue Foch. Charié’s men waited in ambush for three days before they learned that Lilian had already left Montargis.

The notorious Fresnes Prison south of Paris where SOE, OSS, special forces and Resistance members suffered horrific treatment. It was liberated by the Allies on 24 August 1944, but not before the Gestapo murdered many prisoners before it surrendered.

A considerable amount is known about Lilian’s subsequent transfer, following interrogation, from Paris to Germany. She was transferred to Romainville Prison from where she eventually left in the same train as Denise Bloch and Violette Szabo on or about 8 August 1944, reaching Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, via Saarbrücken, on 22 August 1944.

Images from Ravensbrück Womens Concentration Camp – 90 km north of Berlin

On 3 September 1944, still with Denise Bloch and Violette Szabó, she was sent to work at Torgau in north-western Saxony. A considerable amount is known about Lilian at this time due to the fact that they were joined by another SOE French Section agent, Eileen ’Didi’ Nearne who, despite being captured with her radio set, had managed to convince her interrogators that she believed she had been sending messages on behalf of a businessman, and had not realised he was a British agent. Managing to maintain this cover story of a locally recruited French helper, Didi was able to survive and return to Britain to report on her contact with Lilian.

There is also testimony from a Frenchwoman, Jacqueline Bernard, who befriended Lilian on the journey to Torgau and was able, post-war, to relate Lilian’s description of how the Germans had attempted to make her transmit to London as a double agent. She had refused to do so and had withstood the enemy’s interrogation which had sought details of the organisation of SOE French Section.

Lilian was not well on the transport to Torgau and on arrival there was found to be suffering from a bout of fever. Regardless of this, she had to endure a long walk in hot weather from the station to the work camp, only managing to do so with the help of several other women. On arrival, she fainted and was admitted to the camp’s hospital where she was permitted to stay for the entire three weeks that she, Denise Bloch and Violette Szabó were at Torgau. The other two young women successfully claimed they should be treated as prisoners of war as they held British commissions and they were therefore exempted from the work which was in a munitions factory adjacent to the camp.

After their return to Ravensbrück in early October, Lilian, Denise and Violette left again on the 19th of the month as part of a large work party of some 200 women who were sent to Königsberg on the Oder river in East Prussia – today Kaliningrad in Russia. Their destination was a small work camp which was in a poor and dirty condition, having previously been occupied by Russian POWs who had left the straw mattresses full of lice. The work involved enlarging a nearby airfield and building a road through a forest, but after only a few days Lilian again suffered an attack of fever and was sent to the camp hospital.

There, with the help of a sympathetic Polish nurse, she was exempted from the work details – fortunately so, since the women still only had light dresses while the weather conditions included snow and bitterly cold winds. While in hospital at Königsberg, Lilian made friends with another Frenchwoman who was in the next bunk, Mlle. Billot, later Mme Saint-Saens. Billot was later to describe how Lilian’s health further deteriorated at this time, she had difficulty in digesting food and consequently became very thin and weak. What nevertheless continued to impress all who knew Lilian at that time was her spirit and morale, she remained cheerful and relished the occasional news of the Allies’ advances.

When, on or about 21 January 1945 Lillian, Denise and Violette were recalled to Ravensbrück, her French friends were sorry to see her go, but shared the general belief that the transfer was good news. At the very least there would be better hospital facilities at Ravensbrück for Lilian, there was also the widely-expressed view that the three young women might be repatriated in some sort of deal that the Germans were brokering.

Living and working conditions at Ravensbrück

On arrival back at Ravensbrück Lilian was first held in the punishment block where she, Denise and Violette were unable to make contact with their friends in the main body of the camp. By now, Lillian was too weak to walk and after three or four days she was moved again into a solitary confinement cell in the Zellenbau, a segregated semi-bunker block that could not be observed from within the camp.

She was never seen again by any of the other prisoners in the camp and while there were rumours that she and Denise had been released and had been seen back in France, and also in Sweden, the true circumstances of her fate were not discovered until Vera Atkins’s investigations in 1945 and 1946 into the fates of French Section’s missing agents.

Lilian was believed to have been executed between 25 January and 5 February 1945 and reports suggest she was still so ill that she had to be carried on a stretcher for even the short journey from her cell to the adjacent yard where Ravensbrück’s camp commandant, SS-Stürmbannfuhrer Fritz Sühren, was waiting to read out the execution order. SS-Sturmann Schult (or Schulter), then shot each of the three young women, brought forward singly, through the back of the neck using a pistol. Lilian’s body was immediately burned in the camp’s crematorium, only a few metres away.

Due to the lack of a personal file in The National Archives, summaries of Liliane’s service can only come from letters sent to her parents. In one, the head of SOE, Colonel M.J. Buckmaster wrote:

‘She volunteered for this very dangerous work with the full knowledge of all the difficulties and risks attached to it. I can assure you that the work she and others like her did, contributed very greatly to the rapid liberation of France’.

And Pierre Charié, awarded the DSO for his work with, and later command of, the HISTORIAN circuit, described Lilian as:

‘…my closest companion, the most precious, most daring, of my clandestine life. Her magnificent courage, her assiduous labours day and night, made possible the execution in the department of Le Loiret of excellent work that seriously upset German morale. Harried by the Gestapo, we moved together from village to village, farm to farm. We had to transport the radio set, batteries, accumulators, etc sometimes by motor-car or motor-cycle, more often by bicycle. Although frequently tired, thanks to her sang froid and her disregard of danger, she never failed to make one of her radio transmissions’.

In addition to her listing at the F Section Memorial at Valençay, as she held an honorary commission as a Section Officer in the WAAF, Lilian is officially commemorated at the Commonwealth Air Forces Memorial to the Missing at Runnymede in Surrey, panel 277. She is also commemorated: on the memorial at the site of KZ-Ravensbrück to the four F Section women agents executed there; on the memorial at former RAF Tempsford; on the FANY memorial at St. Paul’s Church, Knightsbride, London – as she also held a commission in the FANY; and on the Second World War roll of honour of the British Church in Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro.

Street in Montargis, Centre-Val de Loire, remembering her first name which Lilian used in France

In Montargis, France, there is commemoration of the local maquis in the naming of several roads. Among these is the rue Claudie Rolfe, originally named the rue Lilian Vera Rolfe, but changed to partially reflect the name – Claudie Rodier – by which she was known to the local people. In south London , Lambeth Council’s Vincennes housing estate (so-named due to the twinning of Lambeth with Vincennes, a suburb of Paris) contains three properties commemorating F Section women agents – “Lilian Rolfe House” being one of them, together with “Violette Szabo House” and “Odette House” (after Odette Hallowes). Lilian (like Violette Szabo who lived in the Lambeth/Stockwell area) had links with the borough of Lambeth in that she visited her grandparents who lived in Paulet Road, Camberwell. Museum of the Resistance in Lorris, where Lilian, Pierre Charié, George Wilkinson and Philippe de Vomécourt are commemorated.

Lilian was awarded a posthumous Mention in Despatches by the British and the Croix de Guerre avec Palme by the French Government.

Latest News – 2021

New Memorial in Paris for Lilian Rolfe, WAAF and F Section, SOE

Perseverance has at long last paid off for Barbara Cronk, a member of the Rolfe family. Barbara had long wanted a plaque on the Paris house where Lilian had been born. Not only did she persuade the Paris City authorities that there ought to be one, but she impressed them enough with Lilian’s story that they decided to obtain all necessary permissions and fund it themselves.

The plaque was installed on 19th February 2021 on the building at 32 avenue Duquesne in the 7th arrondissement of Paris and a formal unveiling is to take place when the situation around the Covid pandemic permits.

Lilian V. Rolfe 1914 – 1945

AFHG/GPFA Note: 200,000 French men & women were killed in German concentration camps; 75,000 of which served to one sort of resistance movement or another. A further 20,000 resistants were killed in action or shot soon after arrest. Except for about 30 survivors, almost all the captured Section F (British controlled) and Section RF (Free French controlled) agents or couriers were deliberately murdered as a matter of NAZI policy, most often in gruesome and humiliating circumstances. They were truly beyond courage.

Story: Paul McCue

Presentation and additional research: Ian Reed

French Translation: Geneviève Monneris

Images: SWW2LN & AFHG

19th May 2023 – a plaque commemorating Lilian Rolfe was officially unveiled at the former Rolfe family home at 32 Avenue Duquesnes, Paris 75007 by the Deputy Mayor of Paris, the British High Commissioner, Deputy Mayor of the 7th Arr of Paris & Mayor of Nargis. In attendance was the British Air Attaché and representatives of AFHG/GPFA; Royal British Legion; RAFA and members of the Rolfe family).