Winning the vote for women was a mighty struggle. Securing full liberation for women of color was no less daunting

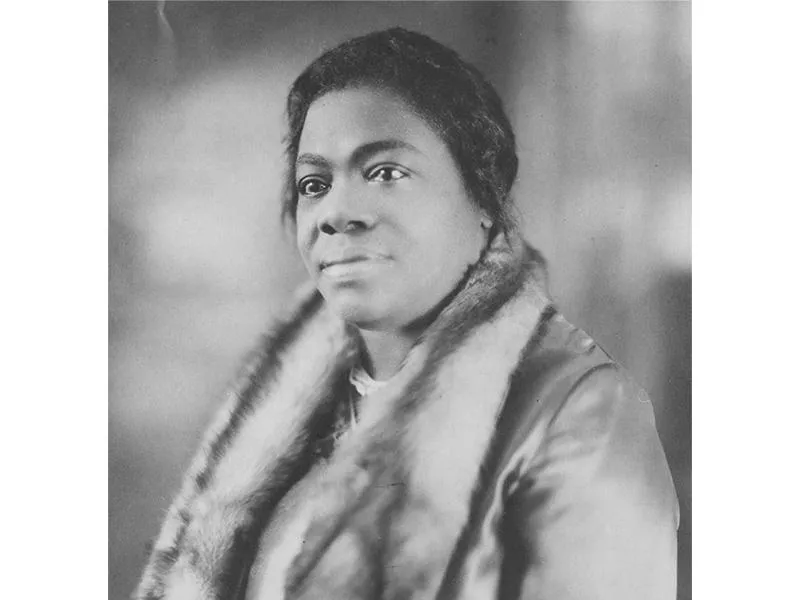

The 19th Amendment, ratified in August 1920, paved the way for American women to vote, but the educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune knew the work had only just begun: The amendment alone would not guarantee political power to black women. Thanks to Bethune’s work that year to register and mobilize black voters in her hometown of Daytona, Florida, new black voters soon outnumbered new white voters in the city. But a reign of terror followed. That fall, the Ku Klux Klan marched on Bethune’s boarding school for black girls; two years later, ahead of the 1922 elections, the Klan paid another threatening visit, as over 100 robed figures carrying banners emblazoned with the words “white supremacy” marched on the school in retaliation against Bethune’s continued efforts to get black women to the polls. Informed of the incoming nightriders, Bethune took charge: “Get the students into the dormitory,” she told the teachers, “get them into bed, do not share what is happening right now.” The students safely tucked in, Bethune directed her faculty: “The Ku Klux Klan is marching on our campus, and they intend to burn some buildings.”

The faculty fanned out across the campus; Bethune stood in the center of the quadrangle and held her head high as the parade entered the campus by one entrance—and promptly exited by another. The Klansmen were on campus for just a few minutes. Perhaps they knew an armed cadre of local black men had decided to lie in wait nearby, ready to fight back if the Klansmen turned violent. Perhaps they assumed the sight of a procession would be enough to keep black citizens from voting.

This Object in History: F-14 Tomcat

If nightriders thought they could frighten Bethune, they were wrong: That week, she showed up at the Daytona polls along with over 100 other black citizens who had come out to vote. That summer, pro-Jim Crow Democratic candidates swept the state, dashing the hopes of black voters who had battled to win a modicum of political influence. Yet Bethune’s unshakable devotion to equality would eventually outlast the mobs that stood in her way.

Bethune’s resolve was a legacy of black Americans’ rise to political power during Reconstruction. Bethune was born in 1875 in South Carolina, where the state’s 1868 constitution guaranteed equal rights to black citizens, many of them formerly enslaved people. Black men joined political parties, voted and held public office, from Richard H. Cain, who served in the State Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives, to Jonathan J. Wright, who sat on the state’s Supreme Court. Yet this period of tenuous equality was soon crushed, and by 1895, a white-led regime had used intimidation and violence to retake control of lawmaking in South Carolina, as it had in other Southern states, and a new state constitution kept black citizens from the polls by imposing literacy tests and property qualifications.

Bethune’s political education began at home. Her mother and grandmother had been born enslaved; Mary, born a decade after slavery’s abolition, was the 15th of 17 children and was sent to school while some of her siblings continued to work on the family farm. After completing studies at Scotia Seminary and, in 1895, at the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, Bethune took a teaching post in Augusta, Georgia, and dedicated herself to educating black children in spite of the barriers that Jim Crow set in their way.

In 1898, Mary married Albertus Bethune, a former teacher; the following year she gave birth to their son Albert. By 1904, the family had moved to Daytona, Florida, where Bethune founded the Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls; originally a boarding school, in 1923 it merged with the nearby Cookman Institute, and in 1941, Bethune-Cookman College was accredited as a four-year liberal arts college. The state’s neglect of public education for black youngsters left a void, and Bethune-Cookman filled it by training students to assume the dual responsibilities of black womanhood and citizenship, as Mary Bethune explained in a 1920 speech: “Negro women have always known struggle. This heritage is just as much to be desired as any other. Our girls should be taught to appreciate it and welcome it.” Bethune had many roles at the school: teacher, administrator, fund-raiser and civil rights advocate.

In 1911, she opened the region’s first hospital for black citizens, McLeod Hospital, named for her parents. Aspiring nurses received hands-on training and provided care to the needy, not least during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Bethune’s close friend and biographer Frances Reynolds Keyser, who served as a dean at her school for 12 years, later wrote: “When the hospital was filled to overflowing, cots were stretched in our large new auditorium and everyone who was on her feet cheerfully enlisted in the service of caring for the sick. The Institution spared neither pains nor money in the discharge of this important duty…and the spread of the disease was checked.” Through such life-saving efforts, Bethune ensured that many white city officials and philanthropists would remain loyal to her for decades to come.

By the 1920s, Bethune had discovered the limits of local politics and began to seek a national platform. In 1924 she assumed the presidency of the largest black women’s political organization in the country, the National Association of Colored Women. By 1935, she was working in Washington, D.C., and the following year played a major role in organizing President Franklin Roosevelt’s Federal Council on Negro Affairs, unofficially known as the “Black Cabinet.”

Bethune, seeing how desperately black Americans needed their share of the benefits of Roosevelt’s New Deal, solidified her influence as a counselor to the president and the only black woman in his inner circle. In 1936, FDR named her head of the new Office of Minority Affairs in the National Youth Administration, making Bethune the most highly placed black woman in the administration. Black Americans had been largely excluded from political appointments since the end of Reconstruction; Bethune resurrected this chance for black Americans to hold sway at the national level and ushered a generation of black policymakers into federal service, including Crystal Bird Fauset, who would become the first black woman in the country to be elected to a state legislature when she joined the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1938. Bethune was aided by the close friendship she’d forged with first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who saw eye to eye with Bethune on civil rights and women’s issues. The two went out of their way to appear together in public, in a conspicuous rejoinder to Jim Crow.

During World War II, Bethune thought that the struggles of black women in the United States mirrored fights against colonialism being waged elsewhere in the Americas, Asia and Africa. Leading the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), which she’d founded in 1935, Bethune worked to ensure that the Women’s Army Corps included black women. In 1945, delegates from 50 Allied nations met to draft the United Nations Charter at a conference in San Francisco; Bethune lobbied Eleanor Roosevelt for a seat at the table—and got one. Working with Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit of India and Eslanda Robeson, an unofficial observer for the Council on African Affairs, Bethune helped solidify the U.N. Charter’s commitment to human rights without regard to race, sex or religion. As she wrote in an open letter, “Through this Conference the Negro becomes closely allied with the darker races of the world, but more importantly he becomes integrated into the structure of the peace and freedom of all people everywhere.”

For half a century, Mary McLeod Bethune led a vanguard of black American women who pointed the nation toward its best ideals. In 1974, the NCNW raised funds to install a bronze likeness of Bethune in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Park; the sculpture faces Abraham Lincoln, whose figure was installed there a century before. The president who issued the Emancipation Proclamation now stands directly facing a daughter of enslaved people who spent her life promoting black women’s liberation.

In 2021, Bethune will be enshrined in the U.S. Capitol, when her likeness will replace that of Confederate Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith to represent Florida in the National Statuary Hall. Bethune continues to galvanize black women, as Florida Representative Val Demings explained in celebrating Bethune’s selection for the Capitol: “Mary McLeod Bethune was the most powerful woman I can remember as a child. She has been an inspiration throughout my whole life.”

“Nobody’s Free Until Everybody’s Free”

After suffrage, women secured further politican wins. These women led the charge —Anna Diamond

Pauli Murray

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/4d/8c4d40a7-92d6-4fdd-9eca-2c31639b2e32/julaug2020_b17_prologue.jpg)

A brilliant legal mind, Mur- ray was an ardent advocate for women’s and civil rights. Thurgood Marshall admired the lawyer’s work and referred to her 1951 book, States’ Laws on Race and Color, as the bible of the civil rights movement. In 1966, Murray helped found the National Organization for Women and, in 1977, became the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Florynce Kennedy

:focal(366x315:367x316)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/2d/dd2dfe76-fd37-46c8-ba23-54df28881c79/julaug2020_b18_prologue.jpg)

An impassioned activist and lawyer educated at Columbia Law School, Kennedy took on cases to advance civil and reproductive rights. She helped organize the 1968 protest against misogyny in the Miss America Pageant, toured the country giving lectures with Gloria Steinem in 1970 and founded the Feminist Party in 1971, which nominated Shirley Chisholm for president in 1972.

Patsy Mink

:focal(650x316:651x317)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d7/05/d7055e06-2dfc-4054-a0b2-e1d4e95a5fac/julaug2020_b16_prologue.jpg)

In 1964, Hawaii gained a second seat in Congress; Mink ran for it and won, becoming the first woman of color elected to Congress. Over 13 terms, she was a fierce proponent of gender and racial equality. She co-authored and championed Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination in federally funded education programs. After her death in 2002, Congress renamed the law in her honor.

Fannie Lou Hamer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/fe/5afea87b-f15f-44be-87c8-d02bd312313a/julaug2020_b20_prologue.jpg)

Born to sharecroppers in Mississippi, Hamer was moved to become an activist after a white doctor forcibly sterilized her in 1961. The following year, Hamer tried to register to vote—and was summarily fired from the plantation where she picked cotton. In 1971, she co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus, which advanced women’s involvement in all areas of political life.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?