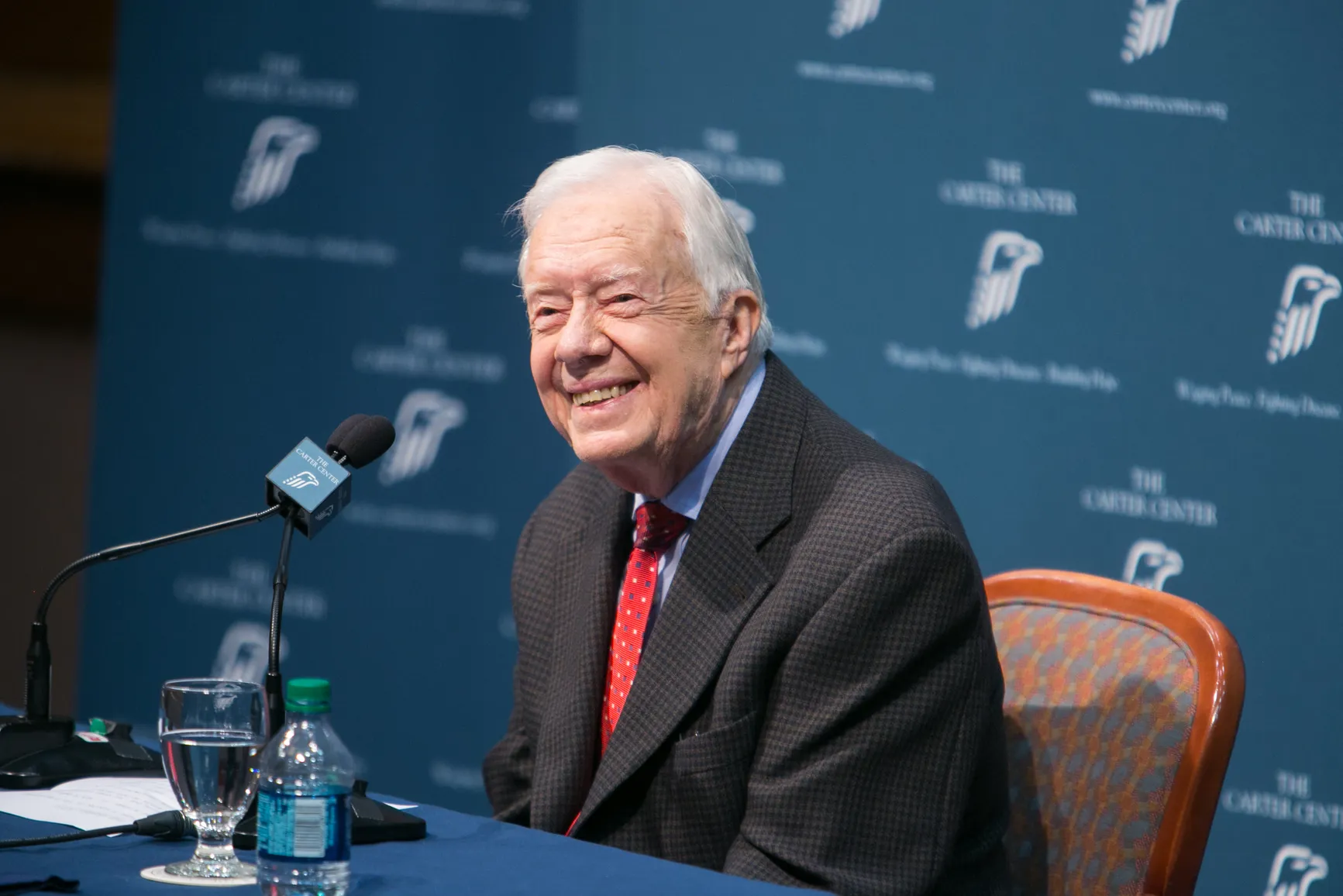

Nine years ago, Jimmy Carter held a news conference at the Carter Center in Atlanta to talk about his cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Then age 91, Carter explained that a bad cold the previous May had led to a thorough physical, which by early August 2015 resulted in a diagnosis of melanoma, an extremely dangerous form of skin cancer. He had liver surgery earlier that month, and doctors identified four spots where the cancer had spread to his brain.

If his diagnosis had come a few years earlier he would have been given about six months to live.

Instead, on Tuesday, the former president celebrates his 100th birthday.

Luck played a role, of course. But there’s no question, experts say, that he’s alive today because of the immune therapy he received.

“It’s kind of a trite term, but in so many ways, he’s kind of the poster child for immune therapy,” said Dr. Stephen Hodi, who directs the Melanoma Center and the Center for Immuno-Oncology at the Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center in Boston. “There were so many issues that he exemplified as a patient.”

Back then, the treatment was a new addition to the cancer arsenal.

Just four years earlier, the Food and Drug Administration had approved the first so-called checkpoint inhibitor, generically called ipilimumab. Carter received the second such drug, pembrolizumab, which was authorized only the year before he was given it.

Now, these treatments and other cancer immunotherapies are among the major pillars of cancer care, alongside surgery, chemotherapy and radiation ‒ not just in melanoma, where the approach first took hold, but in dozens of other tumor types as well.

Like any other patient

Dr. David Lawson said he treated Carter with pembrolizumab because the former president was, at 91, still incredibly healthy and resilient.

In the Aug. 20 news conference, Carter said his one regret about his cancer treatment was that it might interfere with a planned trip to Nepal that fall on behalf of the charity Habitat for Humanity.

Lawson, who works at the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, said he believes he treated Carter the same way he would have treated anyone else.

“The best favor you can do for a famous patient is forget that they’re famous. The cancer doesn’t care,” he said. “I hope it didn’t (change how we treated President Carter). We certainly tried not to let it, but you never know.”

Lawson said he stopped Carter’s pembrolizumab after six months, though he would typically give it for two years. The former president seemed to be responding well and was exposed to a lot of people, so Lawson didn’t want him to have a weakened immune system.

Carter’s treatment came “on the cusp” of the time doctors were first realizing how effective the treatments could be, said Hodi, who conducted the first clinical trials with the drugs.

When Carter was treated in 2015, Hodi said, it was still unclear whether patients whose cancer had spread to the brain could benefit. The fear was that the drugs would cause brain inflammation and worsen patients’ conditions while doing nothing to their tumors.

Research by Hodi and others has since shown that, like Carter, many patients with brain metastases from melanoma can benefit from checkpoint therapy. But today, Hodi said, he would give most patients both pembrolizumab and the drug approved earlier called ipilimumab.

Lawson said he wanted to be aggressive with Carter’s treatment, but not too aggressive.

“That’s why we stopped (the pembrolizumab),” Lawson said. “You never stop worrying, but we got to a point thinking, ‘He’s probably cured of this.'”

Never too old

Age isn’t a barrier to treatment with immunotherapies.

Dr. Antoni Ribas, a melanoma specialist who directs the Tumor Immunology Program at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, said he has given checkpoint inhibitors to patients as old as 96 or 97.

Although older people have weakened immune systems, he said, the fact that the drugs can be effective at such advanced ages shows the immune system remains active throughout life.

“The fact that people in their 80s and 90s can get rid of metastatic melanoma tells us that the immune system is pretty remarkable,” Ribas said. “I would not underestimate the immune system of a 90-year-old.”

Still, doctors tend to be quicker to give older patients “medication holidays” if they suffer side effects, he said. It’s a term that refers to patients taking a break from using a drug, and it can be deployed to assess how well a therapy might be working, relieve side effects and more.

Overall, only about 1 in 20 patients have severe side effects from immunotherapies, with skin rashes and flu-like fatigue the most common relatively minor factors.

The ‘C’ word: Cure

In addition to the immunotherapy and liver surgery, Carter had radiation treatments directed at the four tiny tumors spotted in his brain. But Lawson, Hodi and Ribas agree he would not have lived much more than six months without the pembrolizumab.

“The life expectancy of someone with liver and brain metastases even with radiation and surgery would be counted in months,” Ribas said. “Unleashing the immune system can lead to a normal life.”

Pembrolizumab and ipilimumab ‒ nicknamed “pembro” and “ipi” ‒ are called checkpoint inhibitors because they take off the brake, or checkpoint, that cancer places on the immune system, allowing immunity “soldiers” to get to work fighting the cancer.

Other forms of immunotherapy, many of them still under development, enlist the immune system in other ways. Some first attract immune soldiers to the tumor site, while others target different immune tools.

About half the patients with this extremely dangerous type of skin cancer respond well to immunotherapy, according to a study published earlier this month in The New England Journal of Medicine. Among patients who survived three years with no cancer progression, the study showed, 96% were alive seven years later if they had received both ipilimumab plus a drug similar to pembrolizumab called nivolumab; 97% were alive if they received nivolumab alone, and 88% were alive if they got only ipilimumab.

Before these immunotherapy drugs, maybe 1 in 20 patients would have the possibility of living longer than about six months, Ribas said.

Still, like other cancer doctors, Ribas doesn’t like to set up unrealistic expectations for his patients, “I think we have to start using the word ‘cure.'”

At this point, Ribas and others expect that whatever Carter eventually dies from, it won’t be melanoma.

Looking ahead

Researchers are still trying to get immunotherapies to work for more melanoma patients and more people with other types of cancers.

Studies are underway manipulating different aspects of the immune system, combining different therapies at different times, and improving methods of targeting individual tumors.

What does Carter’s survival for so long mean to the doctors who have devoted their careers to caring for patients like him?

“It makes us look back on the progress on this cancer and how it benefits patients and changes their life,” Ribas said.

Hodi added: “It’s tremendous and very celebratory. It’s fantastic.”

Lawson reflected on his most famous patient.

“He’s just a great guy a great human being,” Lawson said. “I wish him a happy birthday and many more to come.”

Karen Weintraub can be reached at kweintraub@usatoday.com.