In commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, we’re exploring how generations of diverse women have experienced a key concept in American history: independence. Through a multi-faceted oral history project focused on the last 50 years, We Do Declare: Women’s Voices on Independence will explore when, how, and why women have sought independence in their own lives, through the lens of economic power.

The notion of independence and the meaning of economic power has resonated differently across varied groups and time periods—for instance, interdependence and connectivity are key values in many communities, and therefore supporting family or communal goals is more important than individual wishes. Oral histories allow us to hear directly from women about their varied experiences with independence and the ways in which finances and economic issues are connected to this influential concept. By listening to diverse women’s voices and contextualizing their experiences, we can begin to understand the multiple meanings of a word so familiar to Americans. We Do Declare: Women’s Voices on Independence will unfold over the next year and a half, featuring several dozen oral histories and community stories of women from across the country, accompanied by public programming and educational resources, and culminating in an online interactive experience during the country’s semiquincentennial in the summer of 2026.

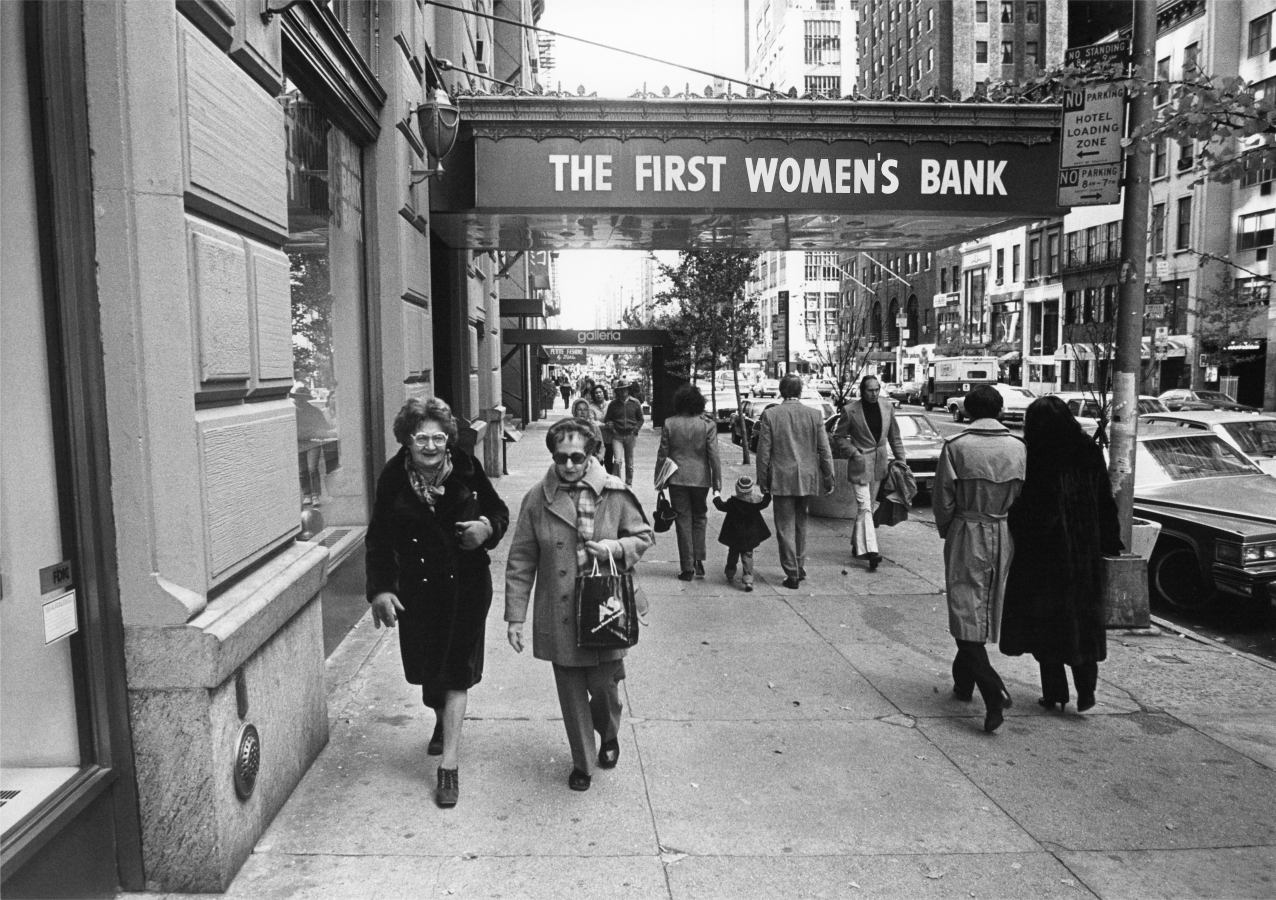

Our exploration of the meaning of economic independence kicks off with four oral history interviews conducted by curator Rachel Seidman. These interviews focus on a singular moment in time in the 1970s when women were pushing for and expanding their economic opportunities. October 28, 2024, marks the 50th anniversary of the passage of the 1974 Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), which made it illegal for banks to discriminate against women applying for loans based on their sex or marital status. Amended in 1976 to extend its protections to include race, color, religion, national origin, age, and receipt of public assistance, ECOA fundamentally changed women’s ability to access credit and capital and shifted their relationship to the banking industry.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=22j1VMKCtNI%3Fautoplay%3D0%26enablejsapi%3D1%26disableKb%3D1%26playsinline%3D0%26start%3D0%26controls%3D0%26cc_load_policy%3D1%26cc_lang_pref%3Den%26hl%3Den%26modestbranding%3D1%26rel%3D0%26iv_load_policy%3D3%26origin%3Dhttps%253A%252F%252Fwomenshistory.si.edu%26widgetid%3D1

The above media is provided by

Each woman interviewed discusses the messages they received about women and money growing up, how they came to understand the notion of financial independence, and what steps they took to advance their own and other women’s economic power. Together, they offer us a glimpse into how social change happens, especially the little-known, yet pivotal history of ECOA and the phenomenon of women’s banks that flourished in the decade after its passage.

Learning from Women’s Voices

The above media is provided by

Emily Card, PhD, served as a legislative fellow in the office of Senator William Brock in the early 1970s and convinced him of the need for a national law to prevent banks from discriminating against women when issuing loans and credit cards. Card herself had experienced such discrimination, and by coordinating with national women’s organizations, she set out to make a difference. Senator Brock asked her for “proof” that the problem was widespread, and within weeks she supplied him with thousands of letters from women across the United States who had faced credit discrimination due to their sex and marital status. Card then helped write the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which passed in 1974.

In this interview, Card recalls her childhood in Tennessee, her educational experiences, and the remarkable story of how she became a key figure in the history of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act. This interview advances historical scholarship by helping us recover the crucial role that Emily Card played in coordinating between women’s rights activists and Senator William Brock of Tennessee to make important legislative change.

I had gotten an issue of Ms. magazine, which was out on the newsstands, and it said “What the 93rd Congress can do for you.” There was an article by a woman named Ellen Sudow that told us we could get equal credit in that year. I called her, actually right away. We met for lunch very quickly, and she briefed me on what she knew. … I started talking to a bunch of different women’s groups. There was a woman from NOW [National Organization of Women], Sharyn Campbell, who had a whole drawer full of 3000 letters that she had gathered up. I was sort of networking around all over the place … I gave [Senator Brock] all the statistics … And then I gave the examples of reasons women couldn’t get credit. He said, well, he didn’t know if a federal law was needed; he thought it could be a state’s right issue. But I said, no, it won’t work that way… we have to have a national law.

After an unsuccessful run for Congress, Card became a nationally known expert on gender, credit, and finances. She wrote multiple books and articles on women’s economic independence and hosted her own television show.

[This interview is presented in audio format only.] WATCH MORE

The above media is provided by

Stephanie Lipscomb worked as a young woman at the Adams National Bank, originally called the Women’s National Bank, in Washington, DC. One of the earliest and most successful of the multiple women’s banks that opened around the country in the 1970s, The Women’s National Bank set out to make sure that women had equal access to credit and financial literacy education at a time when traditional banks were still discriminating against them.

In this interview, Lipscomb recalls her childhood and family life, including the research she and her mother have done about their family’s history as enslaved workers on the Monticello plantation. She discusses the importance of having your own money and reflects on what she learned from her parents in terms of financial independence and expecting respect in business interactions. Lipscomb’s interview advances our understanding of the little-known history of women’s banks, not only in terms of the role they played for customers but for employees as well. She recalls how the Adams National Bank offered employees a special room for their children to play in during working hours. Lipscomb’s interview helps us draw connections between Black women’s racialized and gendered experiences and helps us understand how change unfolds in American history.

“Thank goodness for the women’s bank. Thank goodness that I was able to know some of the history and experience working with some of those people, working with the customers that I met there. I just felt that it took having a women’s bank to be able to empower women to have credit and to have businesses and not be turned away by some man sitting behind a desk saying ‘no,’ because you’re a woman. I just think it’s an important legacy to keep telling the story about it.”

Today Stephanie Lipscomb is vice president at National Capital Bank of Washington, DC.WATCH MORE

The above media is provided by

Jeanne Delaney Hubbard, who spent many years working in community banks, served as CEO of the Adams National Bank from 2005-2008 after serving as Chairman of the board in the 1990s.

In this interview, Hubbard recalls her early life and the women who raised her, her education, her long career in community banks, and her reflections on the role of community and women’s banks in making credit more accessible to people. This interview advances our scholarship on women’s banks, which, as Hubbard points out, are an underrecognized and underappreciated part of late twentieth-century women’s history.

“The women’s bank, you know, it’s not fancy, it’s not razzle dazzle stuff; we didn’t burn our bras. It was more of, we’re going to work behind the scenes and we’re going to see that women are educated about finance, comfortable about saying ‘I can do this like anybody else can,’ and have a place to come and be listened to. And then to actually get them the financial help that they need. So that’s the women’s banks in a nutshell.”

After resigning from the bank, Hubbard earned a graduate certificate in women’s studies at Marshall University, where she undertook a history of the Women’s National Bank and other women’s banks and credit unions from the 1970s and 1980s. She currently works as a consultant and lives in Leesburg, VA.WATCH MORE

The above media is provided by

Rosemary Reed is the owner and president of Double R Productions, which has been in operation since 1987. When she was trying to start the company after losing her television job, Reed applied for small loans at two local banks in Washington, DC, but both turned her down. In desperation, Reed bought the equipment she needed on a credit card. A colleague then suggested she try Adams National bank, where Reed met Stephanie Lipscomb. Lipscomb counseled Reed and provided important financial support and cultural capital to help her get her business off the ground.

In this interview, Reed discusses her childhood and family, her early career in radio and television, and multiple experiences she had with mainstream banks before she discovered Adams National Bank. This interview helps us understand the critical role that access to credit played in Reed’s ability to flourish as an independent entrepreneur and demonstrates the impact that women’s banks like Adams National Bank could have on women. This research helps us see how, even after the passage of the ECOA, women continued to face obstacles in accessing credit and to learn about how women’s banks made a difference for them.

“I’d had such a bad experience with that other bank. Walking into the Abigail Adams National Bank, there were a lot of women, and they were so welcoming and so nice, and they would sit down with me and say ‘Okay, you’re doing this freelance stuff.’ Not making fun of me, not demeaning me, not saying. ‘Oh, well, you’re never going to make it.’ They were encouraging me, and I think they saw that I had the fire in my belly to make this business work.”

In addition to still running Double R Productions, Rosemary Reed has expanded her entrepreneurial endeavors to using her family’s land in Nebraska to grow hemp for fiber that can be used in new kinds of environmentally and economically friendly building materials