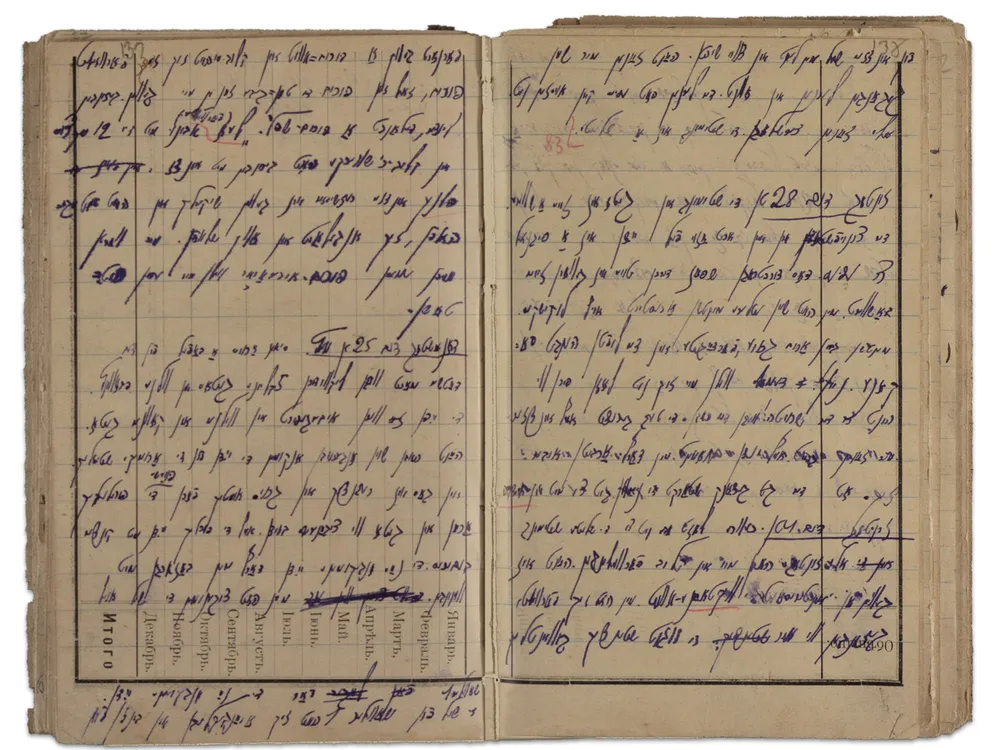

Yitskhok Rudashevski documented his life while hiding from Nazis, as well as folklore told in his community that “must be collected and preserved as a treasure for the future”

Folklore may arise from anywhere and everywhere, even catastrophe. Known sometimes as the folklore of tragedy or the folklore of disaster, these tales have come from the chaos of no man’s land in World War I, the grim uncertainty of the Covid-19 pandemic and even the horrors of the Holocaust in Europe between 1933 and 1945. In such cases, folklore helps to maintain and build the stability, solidarity, cohesiveness and continuity of those affected by the tragedy or disaster.

One remarkable mention of folklore from the Holocaust appears in the exhibition “Yitskhok Rudashevski: A Teenager’s Account of Life and Death in the Vilna Ghetto.” Launched in July 2024 by the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, a Smithsonian Affiliate, it’s the second exhibition in the YIVO Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum.

National Treasure: The Mold Behind the Miracle of Penicillin

Yitskhok Rudashevski was born in Vilna on December 10, 1927, when the city was part of Poland. Now known as Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, the city became Polish territory in 1920, following World War I and the collapse of the Russian Empire. Shortly after the Nazis invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, triggering World War II, the Soviet Union occupied eastern Poland, as per its secret agreement with Nazi Germany, signed on August 23, 1939. The Soviets transferred Vilna to Lithuania, and one year later they occupied and illegally annexed all of Lithuania. When Nazi Germany broke the secret agreement and invaded the Soviet Union on Sunday, June 22, 1941, it took control of Lithuania, and established two Jewish ghettos in the city as part of its “final solution” to murder Lithuania’s entire Jewish population.

The diary that Rudashevski kept from June 1941 to April 1943, written entirely in Yiddish, contains references not only to folklore from the Vilna Ghetto, but also to the Jewish community’s cultural resistance to the Nazi occupation, which ultimately led to the murder of more than 70,000 Jews from Vilna, including Rudashevski, who was shot and killed in early October 1943.

The first entry in Rudashevski’s diary takes place on that day of Nazi invasion in June 1941, a day that begins as “happy and carefree,” but suddenly shifts to total chaos and confusion. “The peaceful blue sky has turned into a volcano that pelts the stunned city with bombs,” the 13-year-old Rudashevski observed. “It became clear to everyone: The Nazis have attacked our land, they have forced a war upon us. Well, we will fight back and fight on until we have beaten the attacker on his own soil.”

Rudashevski’s determination to fight the Nazis remains a constant thread throughout the pages of the diary until it ends suddenly on April 7, 1943, when he prophetically wrote, “At any moment, the worst can happen to us.” Just one day earlier, Rudashevski had recorded the terror of the Nazis’ campaign of genocide:

“All the terrifying details are now already known. … 5,000 Jews were taken to Ponar where they were shot to death. Like wild animals faced with death they began as a matter of life and death to break out of the railway cars. They broke the little windows that were fortified with strong wires. Hundreds of Jews were shot while running away. The railway lines are covered with the dead for a long stretch.”

Yet, even with this devastating knowledge, Rudashevski wrote that he and others on that day “sit in a circle [and] pull ourselves together. We sing a song.” Tragically, half a year later, the Nazis found Rudashevski—just two months shy of his 16th birthday—and his family hiding in an attic room at 24 Dysnos Street in Vilna and murdered them at the Ponar killing site.

Rudashevski’s courage and self-awareness are extraordinary, but what also stands out from the diary is his determination to maintain the culture and traditions of his community. We do not know what song he and his classmates sang in a circle on April 6, 1943, but it may have been one of the songs they had collected as part of their folklore research. His diary entry from November 2, 1942, is especially revealing:

“Today our circle had a very interesting meeting with the poet [Abraham] Sutzkever. He spoke to us about poetry, about the art of poetry in general and about the varieties of poetry. At the meeting, two important and interesting things were decided. We are creating the following branches of our literary circle: Yiddish poetry and most important, a group to concern itself with ghetto-folklore. I was very interested in, and attracted to, this circle. We have already discussed certain details. In the ghetto, before our own eyes, dozens of sayings, curses, good wishes and terms like vashenen—smuggle in—are being created, even songs, jokes and stories that already sound like legends. I feel that I will participate in the circle enthusiastically, because the wonderful ghetto-folklore, etched in blood, which abounds in the streets, must be collected and preserved as a treasure for the future.”

Unfortunately, the documentation collected by this literary circle, which must have been specific examples of this “wonderful ghetto-folklore, etched in blood”—the curses, good wishes, jokes, sayings, songs and stories—did not survive the Nazi liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto in 1943. The only reason that Rudashevski’s diary survived is that his cousin Sore Voloshin found the diary untouched in July 1944 when she returned to the maline (hiding place) in the attic where the Rudashevski family hid from the Nazis on Dysnos Street, following the Red Army’s return to the city. At that time, the Soviet Union resumed its illegal annexation of Lithuania, which lasted until the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

Voloshin had been one of those hiding in the maline, but she managed to escape from the Gestapo prison. She brought Rudashevski’s diary to the poet Sutzkever who had been Rudashevski’s mentor. Sutzkever later displayed the diary in a museum he and Shmerke Kaczerginski created to show materials saved from the Vilna Ghetto by the Paper Brigade, which represented Jewish life and culture in Eastern Europe before World War II. However, with Lithuania’s disappearance into the USSR, Sutzkever feared that the diary might similarly disappear, and he donated it to the YIVO Archives in New York around 1947.

YIVO’s online exhibition has not only translated the diary from Yiddish to English, but has also created an interactive, multimedia experience to tell the story of the diary through some of the latest advancements in digital technology, including animations, videos and interactive 3D environments, drawing on hundreds of artifacts in the YIVO archive that are incorporated into the exhibition.

Jonathan Brent, YIVO’s executive director and CEO, notes in a statement that the exhibition “demonstrates the value of culture as a key element of resistance and survival in times of political, social and existential crisis.”

“Jews, like Yitskhok, defied the Nazi regime by refusing to relinquish their culture and identity,” Brent adds. “Their culture and traditions gave them the moral strength to survive. Even in the hellish ghetto, Rudashevski and his friends participated in youth clubs, history and folklore circles, mock trials, and exhibitions, among other activities to maintain their courage and envision a future.”

Although we no longer have the “wonderful ghetto-folklore” from Vilna, which Rudashevski and others recorded, some 35,000 documents from the Warsaw Ghetto did survive the Holocaust. Collected and hidden in milk cans and tin boxes, the Underground Archive of the Warsaw Ghetto, also known as the Ringelblum Archive, recorded the everyday life of residents—including their artwork, stories, songs and jokes. Among the latter are several that folklorists have termed “gallows humor,” in which the jokes function not only to boost morale, but also to diminish the power of the oppressors—in this case, the Nazis. In one example from the book Who Will Write Our History? by Samuel D. Kassow, a story goes as follows:

“Three Jews mused on the pleasures and amusements they would seek after the war. One would eat his fill; a second would happily visit all German military cemeteries. A third said that he would buy a bicycle and travel all over Germany. ‘Why?’ his friends asked. ‘For a trip of a couple of hours?’”

The teasing optimism that postwar Germany would be so small you could see it all in a couple of hours on a bicycle is an enduring testament to cultural resilience—exactly what Yitskhok Rudashevski and his peers had documented in Vilna.

Get the latest on what’s happening At the Smithsonian in your inbox.