At the National Museum of African American History and Culture, “In Slavery’s Wake” tells the international history of slavery and Black freedom

Kaila PhiloJanuary 27, 2025 3:03 p.m.

Charcoal portraits depict six of the enslaved Africans who were aboard the Amistad, the 19th-century slaving schooner that became the center of a landmark Supreme Court case. After they were stolen from Sierra Leone, shipped to Cuba and put aboard the Amistad headed from Havana to a Puerto Príncipe plantation, the captives rebelled against the slavers to take control of the ship. They killed the captain and the cook and told the enslavers to take the ship back to Africa. Eventually, the Amistad was seized by the United States near Long Island in New York, and the enslaved Africans were imprisoned in Connecticut, where they would go on to win a Supreme Court trial for their freedom.

The charcoal sketches were made by Connecticut artist William H. Townsend while the captives awaited trial in New Haven. Since enslaved Africans were considered property, portraits of them were hard to come by. But Townsend’s work—devoid of the stereotypical racist caricatures often associated with slavery-era imagery—illustrated their personhood.

National Treasure: The Giant Panda Steals Hearts (and Bamboo) at the National Zoo

“They’re a revelation, and they shine a light in the darkness about people who were seeking and seizing and struggling for their own freedom,” says Paul Gardullo, assistant director of history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and director of the Center for the Study of Global Slavery. “Their humanity is undeniable. Their individuality is undeniable.”

Among the portraits is an image of Margru, a young girl who was aboard the ship. She gently smiles for her picture.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/2f/5f2ff6f5-9e43-4e2c-9875-58a8d476750d/isw-046n_il2024-7_3.jpg)

The portraits are featured in a recently unveiled exhibition at the museum, “In Slavery’s Wake: Making Black Freedom in the World,” which brings together over 100 artifacts, 250 images, and ten interactive presentations and films.

The traveling exhibition “privileges the stories of people who, in our contemporary world and from the past, sought ways to find freedom, to make freedom in their lives despite the worst of circumstances,” Gardullo says.

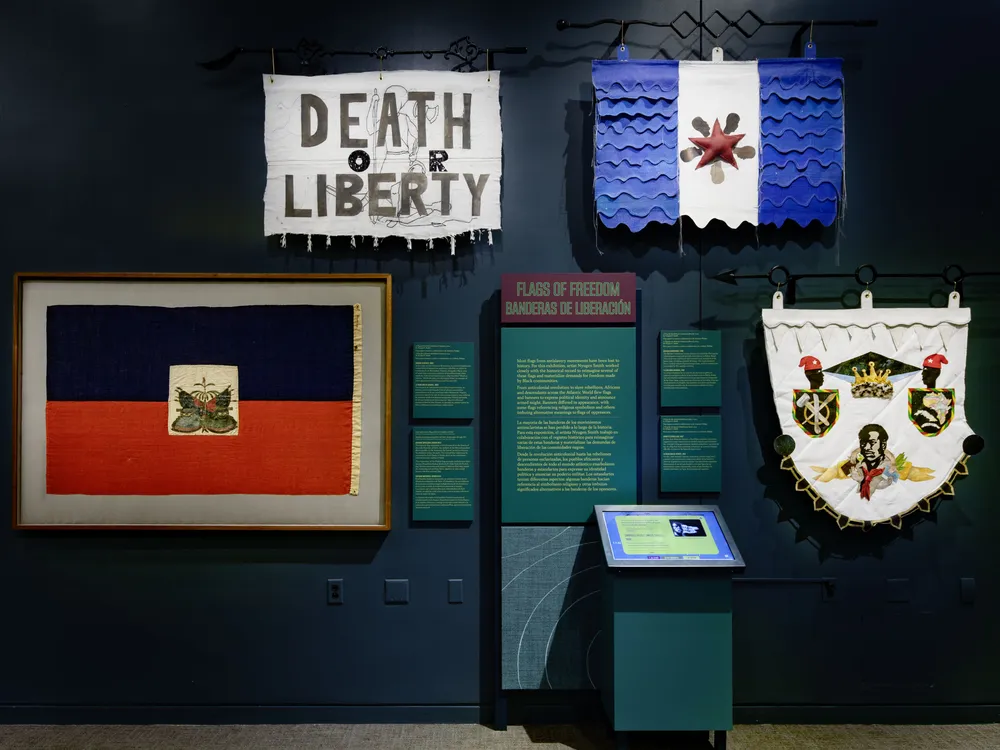

Other artifacts on view include ceremonial cowrie shell baskets, flags from various slave rebellions, and slave badges from markets across North and South America.

“In Slavery’s Wake” began as the brainchild of the Global Curatorial Project, an international network of scholars, curators and educators seeking new ways to engage people with critical points in world history. The project is led by the Washington, D.C. museum and Brown University’s Ruth J. Simmons Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. In 2014, the Simmons Center invited museum professionals to reimagine how they approached their work, beyond just displaying objects in a room to be looked at by the public.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/01/4e/014e1d98-6376-4fd0-a71b-6a43a8e48d44/isw-075_2016_166_2_001.jpg)

In the years since its inception, the project has grown to include museums in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, South Africa and Senegal, among many other places, aiming to connect the worldwide roots of slavery into an expansive international narrative.

“In Slavery’s Wake” is the result of this international work, and it will now make its way to museums on four continents through 2028.

“We really wanted to make sure that people connected the dots to today, but we also wanted to make sure that people didn’t just look at this history as a history of pain,” says Gardullo. “We really felt like this story of freedom, and particularly Black freedom-making, was essential to the storytelling.”

Alongside the older artifacts are contemporary pieces from institutions around the world, by artists meditating on the impact of slavery on Black lives, past and present. On view, for example, is a 2023 portrait of Marème Diarra—a Malian woman formerly enslaved in Mauritania in the 1890s before she escaped with her three children, eventually becoming a respected community leader in Senegal—by Senegalese graffiti artist Akonga.

Other contemporary pieces include Universe of Freedom Making (2024), a large, colorful immersive installation by multimedia artist Daniel Minter, reflecting on the different ways the act of freedom-making can manifest; Blue Print (2009), a vibrant quilt stitched collectively by residents of the Angola Prison Hospice Program; and Époque Coloniale (Colonial Era) (2021), an illustrative tapestry depicting the slave trade in the Democratic Republic of Congo by embroidery artist Lucie Kamuswekera. Keeping true to the exhibition’s premise, the featured artists also come from many different corners of the world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d5/f2/d5f2f6b9-20ba-433e-8e14-5ef7be13d680/ex_sw03_20241209_003.jpg)

South African artist and designer Pola Maneli’s collection of 17 illustrations displays Black liberation practices throughout history. Maneli says in a statement that he pulled from his experience studying “the performativity of Blackness” for his visuals. The pieces, such as Illustration of Bois Caïman Ceremony (2024), blend striking light, color and shadows with intricate patterns and designs to capture the spirit of Black freedom and convey the lives of enslaved people beyond the white gaze. He did extensive research on the landscapes and clothes of the Black figures in his work.

“I hope that [museumgoers] see the people in this history as resilient, dignified and human,” he says in his statement, “and in the process hopefully see themselves in these stories, too.”

Also among the exhibition’s objects is part of an oral history archive called “Unfinished Conversations.” Inspired by cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s proclamation that “identity is an endless, ever-unfinished conversation,” the archive features about 150 interviews with people around the world about the legacy of slavery.

“We filmed interviews with descendant communities talking about this history from their own perspectives, what slavery and colonialism looked like, or the aftereffects of those systems in their local communities,” says researcher Johanna Obenda, who joined the museum as an exhibition developer in 2020, shepherding the collaboration with the museum’s international partners.

“In Slavery’s Wake” also offers a companion book, showcasing 150 high-res images pulled from or inspired by the exhibition and deeper explorations into their significance, alongside essays from historians and scholars.

“We wanted to have the book feel like it was as multi-vocal as this process of learning and building,” Gardullo says.

Obenda emphasizes that “In Slavery’s Wake” is the largest traveling exhibition that the museum has undertaken, and that each of the countries featured in the exhibition has a historical connection to slavery and colonialism. “It’s a global history,” Obenda says. “It’s hard to find somewhere on earth that doesn’t have that connection.”