“Our principle of impartiality is being challenged.”

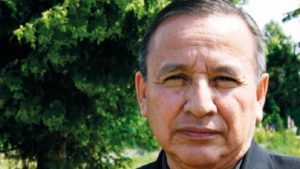

Daniela Mohor

Aid groups trying to tackle soaring humanitarian needs in Haiti are increasingly seen as protecting the gangs, leading them to become targeted by the police and self-defence groups, according to the head of mission in the country for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

“In our case, there is certainly this perception, but that’s the result of the fact that we adhere to the principle of impartiality,” Diana Manilla Arroyo told The New Humanitarian during a wide-ranging interview. “We will always give medical care to anyone who needs it, and we do not ask who they are or what they do. This has created frustration amongst not only the armed forces, but also amongst a part of the civilian population.”

Raging gang violence in the Caribbean nation of 11.7 million has seen the number of displaced people more than triple since December 2023 – from 315,000 to more than a million – even as the provision of basic services and access to support and assistance continues to dwindle.

More than 5,600 people were killed by gang violence in Haiti last year, an overall increase of more than 150% since 2022. Another 2,212 people were injured, and almost 1,500 were kidnapped. Women and girls are especially vulnerable to sexual violence and boys to gang recruitment.

Long a problem in Haiti, armed gangs have grown stronger since President Jovenel Moïse’s assassination in July 2021. They now control more than 85% of the capital, Port-au-Prince, as well as large swathes of the surrounding Ouest department and the neighbouring Artibonite department – considered the country’s breadbasket. Nearly half of Haiti’s population doesn’t have enough to eat, with some two million people facing emergency levels of food insecurity.

In October 2023, the UN Security Council approved the creation of a Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission tasked with helping the Haitian police rein in the rampant gangs.

Largely funded by the United States, the Kenya-led force began deploying in June 2024 and now has nearly 800 police and military officers on the ground. But more than six months after its arrival in Port-au-Prince, it continues to be plagued by a lack of resources and poor planning and has failed to stop the security situation from spinning further out of control.

In recent months, the humanitarian catastrophe has been compounded by the fact that aid groups are coming under increasing attack, making them limit their activities and sometimes suspend their assistance altogether.

In November 2024, a new escalation of violence prompted aid groups and UN agencies to urgently relocate or evacuate some of their staff. A UN helicopterused by the World Food Programme (WFP) to deliver assistance was fired on by gangs and forced into an emergency landing. About two weeks later, Haitian police officers and members of the self-defence movement known as Bwa Kale attacked an MSF ambulance, killing at least two patients and threatening staff. MSF felt it had no choice but to temporarily suspend operations.

Health centres continue to be targeted: Several hospitals have been ransacked and partially destroyed. Three people, including two journalists, were killed and many others wounded during the reopening of Haiti’s largest facility, the General Hospital, on Christmas Day.

“There is an alarming trend of medical facilities being targeted in Haiti,” said Manilla Arroyo. “In the capital, only 30% of all health facilities are functioning.”

In this Q&A with The New Humanitarian, Manilla Arroyo details some of the urgent needs her organisation has identified, shares her concern over the rise of sexual violence, and explains why accessing those in need has become more difficult for MSF and other aid organisations.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The New Humanitarian: MSF has suffered several attacks and threats, how have you managed to continue to work?

Diana Manilla Arroyo: Following the 11 November incident where two of our patients were executed, we received numerous threats against MSF vehicles. That is why we established a dialogue with different authorities. It was positive in many ways, but in the end we still could not obtain any realistic guarantees that another serious incident would not happen again, including the assassination of our patients or more threats of rape and assassination to our staff, to our drivers, and to our patients. So we decided to suspend [our services] for about 22 days.We restarted partially in December, meaning that we did not open all facilities at once, and we decided not to use any ambulances at all because, following 11 November, all of the incidents involved police stopping our cars, alleging that we were transporting members of a gang.

We also decided not to reopen one of the facilities that is called Turgeau, which is an emergency stabilisation centre, because the logic of this facility is that they receive emergency cases, they stabilise them, and then refer them to other facilities for longer-term care. It cannot function without ambulances. We managed to reopen it on 20 January, but we are all being extremely vigilant because we are still not sure about how safe our teams are. And for the other hospitals, we are still maintaining a reduction of ambulance referrals.

This has an impact on the quality of care because sometimes some of those patients have to take public transport – a motorcycle or a van – instead of an MSF ambulance. But in some of the communities we work, the population themselves advised us against continuing ambulance referrals because they understand the risks well… And even in critical situations, the patients [refuse] to leave the area to seek secondary healthcare because of the risks of having the police identify and target them.

The New Humanitarian: Aid organisations are increasingly perceived as protecting gangs, and are also confronted with self-defence groups of the Bwa Kale movement who ally with the police. How has this affected humanitarian organisations’ work?

Manilla Arroyo: This situation is generalised in terms of attacks on healthcare providers. In our case, there is certainly this perception, but that’s the result of the fact that we adhere to the principle of impartiality. We will always give medical care to anyone who needs it, and we do not ask who they are or what they do. This has created frustration amongst not only the armed forces, but also amongst a part of the civilian population. And there sometimes is the perception that [gang members] come in, find medical care, and then go out and repeat whatever they had done before.

One of the points we are really trying to clarify with the police and civilian population is that in the facilities that offer trauma care, bullet wounds and other types of trauma related to violence represent less than 10% of the cases. The rest of trauma cases are primarily accidents on the road. And then, of the other services that the population seek in the emergency hospitals and the mobile clinics, most are related to sexual and reproductive healthcare, with contraception being at the top. The majority of those seeking care are women and children, and some of those patients are seeking contraception as a way to protect themselves from the very real risk of rape.

The New Humanitarian: MSF has raised the alarm about the rise of sexual violence in Haiti. Have you identified changes in the past few years?

Manilla Arroyo: No one is exempt from violence here, but the impact on women and girls is disproportionate. This is something we see in the caseload in our sexual violence services, particularly since 2022. The data keeps getting worse and worse year after year. In 2022, for example, we had just over 1,700 patients. And then, the year after, in the same facilities, we saw over 3,000. In 2024, there were more than 4,000 patients in the same facilities and in a new one we had to open to increase services for sexual violence survivors. And we are not seeing everyone, so the numbers that I’m sharing do not illustrate the whole situation.

In terms of new trends, between 2015 and 2022, the majority of the patients were survivors of intimate partner violence, including both physical and sexual violence, but mostly cases of physical violence. We still see that type of patients, but since 2022 more patients say that they did not know the assailant; more say that the assault included [a weapon] and that there was more than one assailant. This is something that we did not use to see being most of the caseload.

[What] has remained a challenge is that last year, for example, more than 70% of the survivors came… 72 hours [after the rape]. That happens for many reasons: Stigma used to be one top limitation factor, but now it’s primarily due to the levels of violence that sometimes don’t allow them to leave their area of residence because they fear being targeted [just for] living in gang-controlled areas. The other new factor is that so many of our patients are displaced.

The New Humanitarian: What’s the situation like in displacement camps?

Manilla Arroyo: Most of the displaced population goes to live with people that they know. But there are many people living in camps, most of them here in Port-au-Prince, in the metropolitan area, in over 100 internally displaced people sites. In one area where we intervene, the needs are related to access to water, to sanitation and hygiene. We started to work, for example, in a school that is now used to host displaced people. There are about 2,500 people living there, and we found that there are no showers whatsoever and only two toilets for everybody. When we arrived, the septic tank was already full.

This is the situation that women and girls are living in, which adds very much to their vulnerability. There is a need for a scaled-up humanitarian response on many fronts, but the provision of hygiene and sanitation services in these displacement sites is really important. Another challenge that we see is that it’s difficult to improve these very critical conditions because the government wants to limit long-term investments so that [the displaced] don’t stay there for a very long time. But, at this point, there’s nowhere else for the population to go. So, the construction of emergency hygiene facilities, including latrines and showers, and ensuring their regular maintenance as well as the provision of essential hygiene items – at least of soap and chlorine – are really necessary…

One of the main problems is skin-related infections: There are many people with scabies because they are living in very unhygienic conditions. This is not only true for people in displacement sites; it is true for many areas of the city – many of which are under the control of armed groups – where there are no public services whatsoever. In many of the areas where we do mobile clinics, there isn’t one single functional state hospital or health centre, and that’s why we go there, when the security situation allows us to.

The New Humanitarian: Currently, nearly half of the Haitian population faces food insecurity. Are you seeing many cases of malnutrition?

Manilla Arroyo: That’s one of the main puzzles we are trying to solve, because we do screening for malnutrition in all of the health facilities where we do primary healthcare and so far we are seeing very few cases. So, either women with malnourished children are not coming, or malnourished people are perhaps located in areas outside of the metropolitan area. These are our hypotheses.

The New Humanitarian: The US Federal Aviation Administration has suspended all flights to Port-au-Prince until March, the seaports open on and off, and all roads out of the capital are controlled by gangs. Last year, MSF warned that it could run out of supplies. Have you?

Manilla Arroyo: We are still OK. The intermittent opening of the port is definitely an issue, but we have had to find alternatives by road, because even if some commercial airlines have restarted [their flights to Port-au-Prince], we do not consider there is a context yet where the risk of another airplane being targeted has gone away.

The reason it is possible for us [to use roads] is because we negotiate that passage and that access, and that’s something that we have done since forever. As we do in all places in the world, we establish a dialogue with everybody: the authorities, armed groups, and self-defence groups. We explain to everyone that we are here to provide services free of charge to everyone that needs them, regardless of who they are; and that’s what has given us access here and everywhere else.

The New Humanitarian: In Haiti, are these negotiations now harder than they used to be?

Manilla Arroyo: They are different, because the context has deteriorated so much… Negotiations are important with everyone that is involved in the different dynamics, and we are trying to adapt to situations where the violence has changed from the police side. That’s something that we saw on 11 November when the police and self-defence groups murdered two of our patients. That is a new context – something that we had not seen before. But we have no other choice than to adapt.

Is it harder? In any context, we negotiate with all the armed groups that we have to in order to obtain access. It’s just that in some parts of the world, access from authorities, including the police, are given to humanitarian organisations, and that is not something we are seeing in Haiti.

In Haiti, we struggle to obtain respect from authorities that are supposed to protect everyone, including humanitarian agencies; our principle of impartiality is being challenged. But we are doing everything we can to maintain a dialogue, so we started to offer awareness training sessions to the different police stations and specialised units in the city about what we do, why we do it. We are trying to clarify that there are rules established by the Ministry of Justice with certain criteria to meet before a health facility gives information about a patient.

The New Humanitarian: Some people talk about turning the MSS into a peacekeeping mission, others ask for a Haitian solution. What do you think is needed for aid groups to be able to better provide services to the people in need?

Manilla Arroyo: We hope that there can be an established government that can make decisions and re-establish very much needed services. In healthcare, there have been multiple changes of the Minister of Health, for example. It is very difficult to even propose and discuss solutions when there isn’t a cabinet that is there to lead the work.

Since late last year, there has been a change of prime minister; there have been a number of changes in the cabinet ever since, and that makes any small progress even harder.

The New Humanitarian: Is there any other issue you want to raise attention to?

Manilla Arroyo: I hope that the international community can recognise the gendered consequences of the extreme levels of violence. And also, sometimes, I wonder how many more patients we have to see next year for there to be more funding for the crisis in Haiti, because, even last year, the [humanitarian] response was very underfunded and right now we are not really seeing any signs that that’s about to change.

Edited by Andrew Gully.