After a summer of racial reckoning, is the country finally ready to learn the truth about the ‘first Thanksgiving’?

The traditional story of Thanksgiving, and by extension the Pilgrims — the one repeated in school history books and given the Peanuts treatment in “A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving” — doesn’t start in 1620, with the cold and seasick Pilgrims stepping off the Mayflower onto Plymouth Rock.

It also doesn’t start a year later, with the Pilgrims and the native Wampanoag all sitting together to “break bread” and celebrate their first successful harvest and a long, harmonious relationship to come.

It doesn’t start there because those things never happened, despite being immortalized in American mythos for generations.

The Pilgrims spent only a few weeks of 1620 in the Wampanoag village of Patuxet, which they would rename Plimoth (now Plymouth), and they certainly didn’t step off onto Plymouth Rock. As for that 1621 feast — the supposed genesis of today’s Thanksgiving tradition — there was a small feast, but the Wampanoag were not invited, they showed up later. Their role in helping the Pilgrims survive by sharing resources and wisdom went unacknowledged that day, according to accounts of the toasts given by Pilgrim leaders.

Lincoln’s first Thanksgiving Day didn’t mention Pilgrims

The first national Thanksgiving Day did not invoke the Pilgrims at all. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln declared a Thanksgiving Day on the last Thursday of November, looking to reconcile a country in the throes of the Civil War.

On a parallel track, the story of the Pilgrim forefathers coming to the New World and founding America for religious freedom gained steam, as New England Protestants wielded the myth to gain the top spot in the country’s cultural hierarchy, above Catholics and immigrants, according to historian David Silverman in his book “This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving.”

As Americans looked for an origin story that wasn’t soaked in the blood of Native Americans or built on the backs of slavery, the humble, bloodless story of the 102 Pilgrims forging a path in the New World in search of religious freedom was just what they needed, according to Silverman. Regardless of whether it was rooted in historical fact, it became accepted as such.

In 1963, these two tracks crossed when President John F. Kennedy, whose family frolicked in the home of the native Nauset and Aquinnah people on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, immortalized them in his own Thanksgiving Day proclamation, baking the plaits together like the bread broken and shared in the mythic first Thanksgiving feast.

The historically accurate story of the Pilgrims and the founding of Plymouth Colony 400 years ago this month is not in most school history books. It also is not the one you’ll find at Pilgrim Memorial Park in Plymouth, home of the famed Plymouth Rock and the Mayflower II, a replica of the cargo ship turned people carrier the Pilgrims crammed into to cross the Atlantic.

The more historically accurate telling is gaining a foothold in small circles, as members of the Herring Pond, Mashpee and AquinnahWampanoag tribes; Michele Pecoraro, executive director of Plymouth 400, who is helping lead the anniversary commemoration; and Silverman bring the documented facts to light.

“How are we supposed to improve on this sorry record if we don’t understand the sorry record?” asked Silverman, a George Washington University professor.

“I think the only way forward is to understand the history the way that it happened,” Steven Peters, a spokesman for the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, said. He and other Mashpee and Herring Pond Wampanoag tribe members have been working with museums and on platforms such as Vimeo to elevate the history of the indigenous people who lived in the region for thousands of years before the Pilgrims arrived.

“At that point, it really changes your perspective.”

Hostility, slavery and pandemic

Tradition dictates the Pilgrims’ story starts in September 1620, with the departure of the Mayflower, packed with colonists and sailors, leaving England to set sail for the New World.

But starting there ignores years of European contact with the Native people of New England, and paints the Wampanoag and their neighbors in the broad stroke of simplicity, ignoring the complex regional relationships and politicking at play.

The story could start a century earlier, in 1524, at the first known contact between Native Americans in southern New England and Europeans, in Narragansett Bay near Aquidneck Island.

Or it could start in 1602, when Bartholomew Gosnold visited Cape Cod and what’s now known as Martha’s Vineyard, where contact with the Wampanoag started with trading and ended in violence. As Silverman writes in his book, future annual encounters between the two would follow this same high-tension pattern.

Or in 1614, when a Nauset (Cape Cod) tribe member named Epenow was captured by Europeans and kept in bondage for three years. He engineered an escape and returned to his people on Martha’s Vineyard. That same year, Tisquantum, later known as Squanto, and 19 other Wampanoag men were lured on to an English ship, taken captive and sold into slavery.

Tisquantum, who spent time in Spain and London, would later return to Patuxet, and he and Epenow would play important roles in burgeoning Wampanoag-Pilgrim relations. Only Squanto was immortalized in the Pilgrim story.

But perhaps the best starting point, according to Peters and other historians, is 1616, when a lethal pandemic tore through many Wampanoag villages. In three years, once populous villages like Patuxet, where the Pilgrims would eventually settle, were “utterly void” of people, as English explorer Thomas Dermer wrote. Further threatening the existence of the Wampanoag, the Narragansett Tribe, their powerful western rivals, were left largely untouched.

“We weren’t used to diseases here,” said Hazel Currence, an elder with the Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe, which lived in Patuxet. “Our systems were not used to the illnesses that came with the Europeans and the Pilgrims.”

So by 1620, the Wampanoag, as Peters describes, were in a “difficult spot,” shaped by years of volatile contact with Europeans, slavery, regional threats to their power and a mysterious, devastating illness.

“For me, that’s a really important place to start, because you understand the big decisions that were made,” Peters said. “It would have been a hugely complex situation.”

Why Massasoit helped the Pilgrims

When the Mayflower anchored off what is now known as Provincetown, the Pilgrims found themselves not in a vast, untouched land held for them by divine providence, but amid indigenous people wary and distrustful of Europeans, and the complex politics of rival tribes.

It’s hard to separate the Pilgrims from what the United States would eventually become, Silverman said. It’s easy to believe they arrived here seeking religious freedom and intending to eventually form their own country based on those ideals, he said.

“Many white Americans hold it very dear, the idea that the main impetus for colonization was the search for religious freedom,” Silverman said. “If you ask the general public, even educated people, that’s the most common explanation. It’s not right.”

The congregation of Puritans within the Pilgrims did break off from the Church of England for religious reasons, but that brought them to Holland, where they were free to practice their religion. After a decade of struggling to find jobs and fearing the Dutch influence on their children, the congregants sought a charter from The London Company to start a colony in America, although it was originally granted for land around the mouth of the Hudson River.

The Pilgrims’ main concerns were their own survival in the New World and turning a profit for those who backed the venture. That survival was made possible with help from the Wampanoag, the piece left unsaid at the feast that would become Thanksgiving.

The decision to help the Pilgrims, whose ilk had been raiding Native villages and enslaving their people for nearly a century, came after they stole Native food and seed stores and dug up Native graves, pocketing funerary offerings, as described by Pilgrim leader Edward Winslow in “Mourt’s Relation: A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth,” published in 1622.

That decision was made by Ousamequin, more commonly known as Massasoit, which means “great sachem.” In a structure that Peters says was far closer to a democratic government than the Pilgrim government, Wampanoag territory was organized into sachemships, each with a sachem — a leader — who would oversee that particular village. Sachems ruled by the will of the people. Each sachemship was independent but had relationships with the other sachemships, all coming under the purview of the great sachem.

Massasoit has gone through a bit of a rebrand in the ensuing centuries to be painted as the “protector and preserver” of the Pilgrims — as it says on the statue dedicated to him overlooking Plymouth Rock. But his decision to allow the Pilgrims to stay at Patuxet and eventually provide them aid after they were driven off the Cape, Peters said, had less to do with a sense of dutiful benevolence and more to do with a careful weighing of circumstances and outcomes.

Driving off or killing the Pilgrims, as many tribes, including the Nauset and specifically Epenow, wanted, was a valid option. From their point of view, whatever benefit they might gain would not be worth the threat of betrayal, violence and enslavement that seemed to follow contact with the Europeans. But it would cost valuable warriors, in short supply after the pandemic, and there was the risk of Europeans returning in overwhelming numbers or, worse, sailing around the Outer Cape to take their guns, knives and armor to the Narragansett, according to Silverman.

Allowing the Pilgrims to settle and establishing diplomatic relations with them, even providing aid, brought risks but also reward. The guns, knives and armor the Pilgrims carried would intimidate enemies threatening Wampanoag territory. And, after generations of trading secondhand and thirdhand for coveted European goods from neighboring Native peoples, the Wampanoag would finally gain a firsthand source and considerable trading power.

Massasoit weighed the risks and concluded it was better to have the danger on his side than have to face it.

“We needed a friend,” Peters said. “We needed an ally. That would have been a really difficult decision for them to make.”

Wampanoag and Pilgrims: A deal and a meal

As these debates were happening among the Wampanoag, the Pilgrims, most of whom were still living on the cramped and creaking Mayflower, struggled to survive the winter. Half of them died of illness, cold, starvation or a combination of the three.

Throughout the season, the Wampanoag made their presence known but did not approach until February, when Samoset, a visiting Abenaki tribesman from Maine, approached Pilgrim leaders. He spoke English and carried a subtle message — the Wampanoag were ready for peace or war with their new neighbors, and the Pilgrims needed to make their intentions clear.

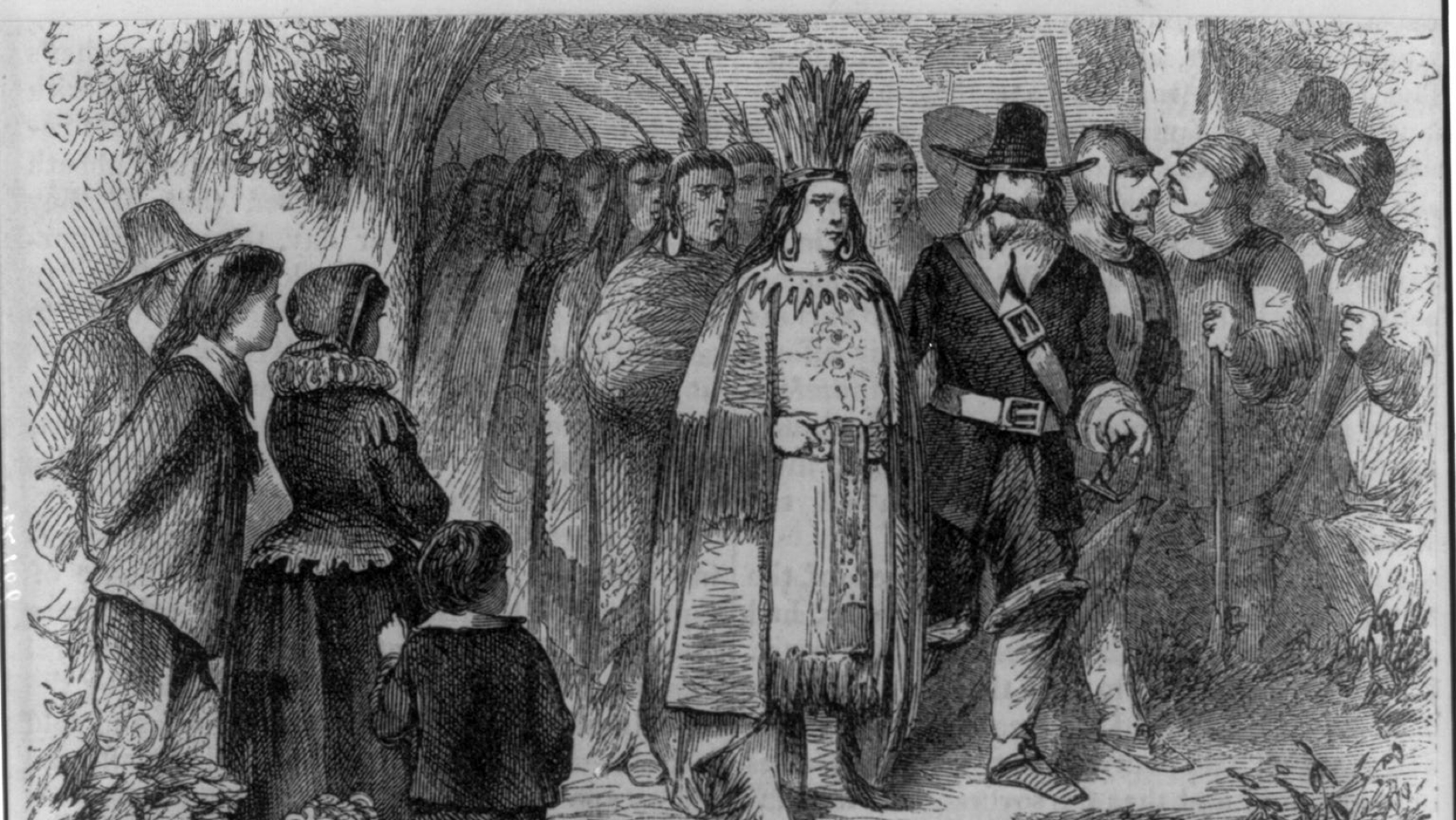

Several weeks later, in late March, diplomatic relations between the two groups formally opened when Massasoit arrived in Plymouth, his face painted deep red, and flanked by about 60 intimidating warriors. With Tisquantum acting as a broker, the two groups worked out a kind of alliance through a series of visits, exchanges and the belief, at least on the part of the Wampanoag, that this small band of Pilgrims would stay just that: small.

“I don’t think anyone at that point would have gone into an agreement with the Pilgrims if they knew how quickly they would multiply and start arriving,” Peters said.

Several months later, after receiving help and protection from the Wampanoag, the Pilgrims held the harvest feast that would form the crux of the Thanksgiving myth centuries later. Wampanoag members were not even invited, but they showed up. A group of about 100 men and Massasoit came not to celebrate but, according to Peters, mostly as a reminder that they controlled the land the Pilgrims were staying on and they vastly outnumbered their new European neighbors.

This is where the traditional telling of the Pilgrims and the Thanksgiving myth ends, with the two groups sitting down to dinner, celebrating their partnership and, for the Pilgrims, celebrating their successful colony and toasting to a future to come. But in the same way the real story stretches back before the arrival of the Pilgrims, it stretches forward.

In a little more than 50 years, European settlers would vastly outnumber the indigenous people, with growing settlements such as the Massachusetts Bay Colony to the north and Rhode Island to the south.

By the 1670s Massasoit was dead and his son Wamsutta had died after he was imprisoned in Plymouth for negotiating a land sale to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. At the same time, colonists were pressing deeper and deeper across the region. Relations between the settlers and the Native people would deteriorate into the devastating King Philip’s War, which ended with death, enslavement or displacement for the majority of the Native people living in southern New England.

The head of another of Massasoit’s sons, Metacomet, better known as King Philip, was mounted on a pike outside Plymouth Colony as a warning, and the descendants of Massasoit, the Pilgrims’ great “protector and preserver,” were captured and sold into slavery in the West Indies.

There’s a reason this part of the story did not make it into school history books and pageants or get remembered on Thanksgiving.

“It’s not a fun story,” Peters said, but its telling brings the focus away from the white Europeans, the Pilgrims, and shifts the balance back to the people who were harmed. Its telling builds the empathy that has been sorely lacking when it comes to Native American lives.

Raising up Native voices

Trying to move that focus, as Michele Pecoraro and Plymouth 400 have done for their commemoration, comes with pushback — people saying they shouldn’t use their organization and the 400th anniversary to disparage the Pilgrims. But when you’ve been telling a story one way for four centuries, any change feels like a monumental one, she said.

“I do believe that the way we’ve gone about it is as balanced as we could make it,” Pecoraro said. “In order to balance something like this, you have to swing the pendulum a little more to one side.”

To bring the commemorations into the 21st century, Pecoraro and her group worked to elevate the voices of the Wampanoag, who still live in southern New England.

The Wampanoag have survived and clung to their culture despite centuries of systemic removal from their land, destruction of their culture and denial of their rights. More recently, the Trump administration has been working to revoke reservation status for hundreds of acres of previously recognized Mashpee Wampanoag tribal lands.

“Out of the 69 tribes of just Wampanoag people who lived here pre-contact, only three — the Herring Pond, the Aquinnah and the Mashpee, plus a band of Assonet peoples, are still here,” said Troy Currence, a medicine man with the Herring Pond Tribe. “We’re lucky to be one of them. We survived. We’re still here. We have a chance to reclaim our language and our history and re-educate people. We didn’t go away, we adapted.”

At the same time, Peters does not think Thanksgiving should go the way of Confederate statues and names of slaveholders on buildings as the nation reckons with its history.

He will continue to celebrate Thanksgiving — something he and his family do every year, after the National Day of Mourning in Plymouth. But it is important to bring the other side of history to light, he said, correcting inaccuracies and adding context to monuments and museums.

“Even though it’s inaccurate, we can’t just bury it,” he said. “There’s a place where those things do belong, as a point that we don’t make that mistake ever again.”