Sixty years ago, as Southern governors criticized civil rights protests and fought integration, one broke ranks and gave a remarkable inauguration address: He called for equal opportunities for all his state’s residents.

North Carolina’s Terry Sanford, then 43 years old, was one of the first major Southern politicians to endorse John F. Kennedy for president. The two Democrats — energetic World War II veterans born three months apart — campaigned together across North Carolina in the fall of 1960. Sanford won the governor’s race and helped Kennedy carry the state in that nail-biting election.

Eight weeks later, with Kennedy’s brother Robert in the audience, Sanford took to the stage of Raleigh’s crowded Memorial Auditorium, bedecked with red, white and blue bunting, and gave his first address as governor.

“We are not going to forget, as we move into the challenging and demanding years ahead, that no group of our citizens can be denied the right to participate in the opportunities of first-class citizenship,” Sanford said near the end of his speech. He called for North Carolina to extend its spirit of goodwill so that its energy could be “directed toward building a better and more fruitful life for all the people of our state.”

Sanford spoke only a few sentences on issues of race. Yet those sentences were starkly different from the statements of other Southern governors of that era.

Alabama Gov. George Wallace, in his first inauguration address in 1963, with his head cocked to the side on that cold January day outside the state capitol in Montgomery, said passionately: “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw a line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say, segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever!”

In style and substance, Wallace and Sanford represented opposite ends of the Democratic spectrum in the one-party South of that era. Wallace once said of Sanford: “Hell, you ever heard him speak? He’ll bore yo’ ass off.”

Sanford wasn’t an entertaining speaker. But the moral courage and decency of his inaugural address stands out 60 years later and was repeated throughout his four years as governor. Later in his term, Sanford would talk more forcefully, and in more depth, about civil rights.

He said the South needed to set itself free “from hate, from demagoguery.” He called for an end to discrimination in employment (“it is honest and fair for us to give all men and women their best chance in life”). Shortly after John Kennedy died, Sanford supported President Lyndon B. Johnson’s bold stance on civil rights. “The president of a free people cannot condone second-class citizenship,” Sanford said.

Sanford’s statements marked a break with about 250 years of North Carolina history. Since the first enslaved people were brought to the colony in about 1700, its White leaders, with exceptions during Reconstruction, endorsed an intimidating system of apartheid for African Americans.

The violence of the 1898 coup in Wilmington, in which white supremacists overthrew the elected Black local leadership (described in “Wilmington’s Lie” by David Zucchino), gave way to a system of Jim Crow segregation that disenfranchised Black people and made them second-class citizens. It was that system that four Black college students protested when they sat down at a Woolworth’s counter in Greensboro in February 1960 and refused to leave until they were served, sparking a wave of sit-in protests across North Carolina and the South.

Taken together, Sanford’s words as governor created a kind of second Emancipation Proclamation for North Carolina. His inauguration speech and other comments signaled to the state’s Black residents that, as Sam Cooke would sing a few years later, change was on its way.

Sanford’s words “created a climate so you could see a world where equality might exist and was achievable,” said state Sen. Dan Blue (D), who was a student in a rural segregated school in North Carolina in the early 1960s and later became the state’s first Black speaker of the House. Combined with Sanford’s aggressive steps to improve schools, “I started thinking I could do anything I wanted to,” Blue said.

Sanford was the first Southern governor to call for employment without regard to race or creed. While other Southern governors were blocking integration, Sanford started Good Neighbor Councils to encourage businesses to hire Black workers and to advance cooperation between the races. He launched an aggressive campaign to hire more Black men and women in state jobs.

“He was part of this new progressive, Kennedy-esque environment,” Blue said. “We were very aware of what was happening in Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Virginia. The contrast was palpable in North Carolina. Sanford was the cause of that.”

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

Sanford had not campaigned for civil rights. Locked in a tough primary against a strong segregationist, he dodged the issue. If he’d attempted to push for civil rights, “You wouldn’t be sitting here talking to me” because he would have lost, he told me shortly before he died in 1998, when I was working on a book about him.

But with his inauguration address, he pivoted. “The most difficult thing I did was the most invisible thing. That was to turn the attitude on the race issue,” Sanford once told the News & Observer’s Rob Christensen. “I realized that the lines of history were intersecting right there as I took the governorship.”

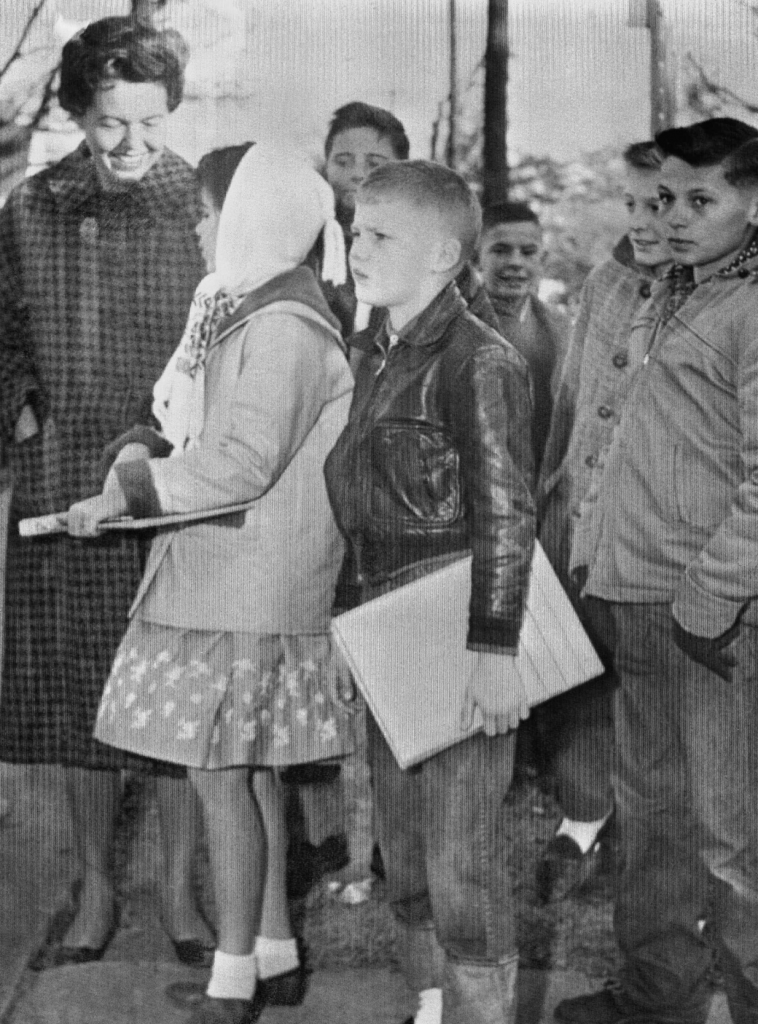

About the time of his inauguration, Sanford and his wife decided to send their two young children to a public elementary school near the governor’s residence that had been integrated the previous fall by 7-year-old William Campbell. It was the first public school in Raleigh in which a Black student attended school with White children.

Sending his children to the school “was an astounding breach of Southern racial protocol,” said Campbell, the former mayor of Atlanta who grew up in Raleigh as the child of civil rights activists. “It was an important symbol for the governor to make that decision. It became a national story. It spoke to where his heart was.”

Sanford’s top issue was improving public schools. Per pupil spending in North Carolina then was well below the national average. As governor, he persuaded the state legislature to raise taxes and use the proceeds to make schools better. His plan added 2,800 teachers, raised teacher pay 22 percent, improved teacher training, doubled library money and increased money for school supplies.

Sanford’s schools program linked together the educational fate of all children — Black and White — and in doing so expanded opportunities for all.

He was a governor of unusual energy, creativity and vision. A Harvard University study in 1981 ranked Sanford as one of the 10 best governors of the century. Campbell considers Sanford one of the greatest governors in American history and the finest Southern governor. “His words and actions and thoughtfulness mattered,” Campbell said. “He stood out as a beacon of hope for African Americans, not just in North Carolina but across the country.”

The NAACP’s Roy Wilkins, one of the “Big Four” civil rights leaders, gave a shout-out to Sanford in his March on Washington speech in 1963 when he called on lawmakers “to be as brave as our sit-ins and our marchers, to be as daring as James Meredith, to be as unafraid as the nine children of Little Rock. And to be as forthright as the governor of North Carolina.”

By law, Sanford could not run for reelection. As his term progressed, his popularity diminished. He’d spent political capital in getting his schools program passed, and his words and actions on race further eroded his support among White voters. At one point, three out of five voters were dissatisfied with his performance as governor. When the 1964 governor’s race became a referendum on his policies, his candidate lost badly.

In 1972, Sanford, then president of Duke University, ran for president of the United States. In the Democratic primary in his home state, he was humiliated by his old antithesis Wallace, who beat him decisively. It seemed Sanford’s political career was over.

But in 1986 he ran for the U.S. Senate and won — only to be turned out of office by voters after one term. North Carolina always was ambivalent about Sanford; he ran in statewide elections four times, winning twice and losing twice.

Sanford believed segregation not only held back Black people but also held back North Carolina and the South from fully joining the rest of the nation. “I want North Carolina to move into the mainstream of America,” he said in his inauguration address.

He thought leaders should lead, and he was willing to take political risks to move his state forward. A former paratrooper who’d fought at the Battle of the Bulge, he showed during his jam-packed life both physical and moral courage. “You’re not elected to be a poll-taker,” Sanford once said. “You’re elected to provide some leadership.” In his inauguration address, he did.

John Drescher is a national politics editor at The Washington Post.