A 96-year-old veteran was near death. Then he met his social worker.

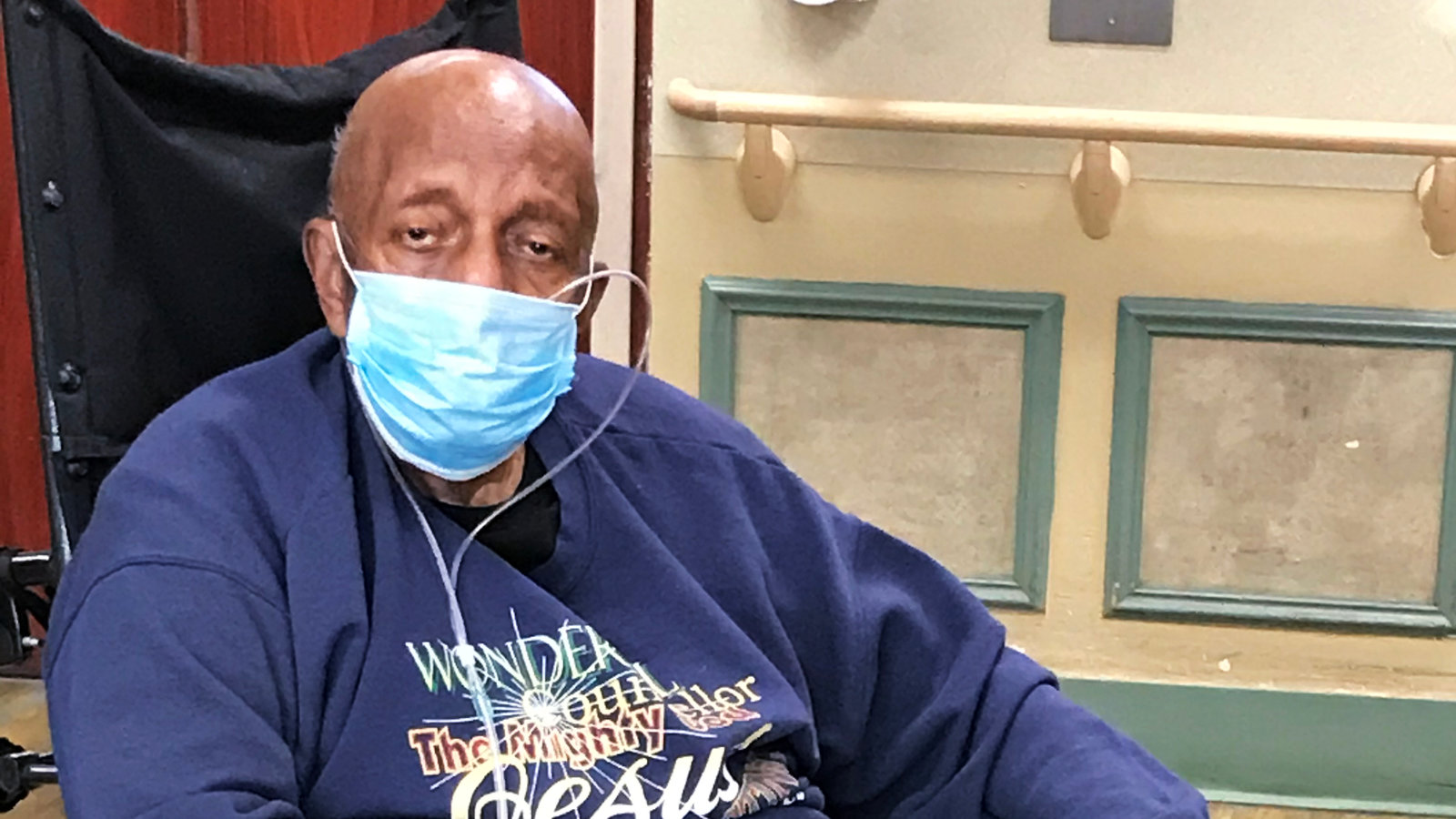

NEW YORK — The outlook for the patient assigned to Capt. Eric Dungan on May 1 was bleak: George Crouch , 96, seemed to have given up on life.His beloved wife had died of COVID-19, and Crouch was also battling the illness in the hospital. Since his wife’s death in late April, he was refusing medical

His beloved wife had died of COVID-19, and Crouch was also battling the illness in the hospital. Since his wife’s death in late April, he was refusing medical care and would not eat.Dungan, a trained social worker in the U.S. Army Reserves, had been deployed from Indiana to New York City to help hospitals counsel the sick during the coronavirus crisis. Many of his patients at Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx had already died of the illness, and given Crouch’s age, condition and temperament, Dungan braced for the worst.

A nurse stopped him on his way to visit Crouch for the first time. Did Dungan know, the nurse asked, that Crouch was a veteran of World War II?“I always see World War II vets as national treasures,” Dungan said. “He did not disappoint.”The soldiers’ disparate paths had collided at that hospital bedside.

Crouch was decades out of the Army; Dungan, 46, had only just signed up for the reserves, driven to enlist after the death of his own father, a veteran.Crouch had lived in New York City for most of his life. Dungan, from Muncie, Indiana, had never been to the city. His deployment to Jacobi was his first ever in uniform, part of the same military-backed effort that brought the USNS Comfort hospital ship to the Hudson River.

But bonded by their time in the service, the two men connected. Through their friendship, Crouch found something to live for, his family believes.“Captain Eric Dungan had immense impact on him. And on us, we really love him,” said Kai Adwoa-Thomas, Crouch’s daughter.

Crouch had faced fierce enemies before. He had served in the Army for both the Second World War and the Korean War, rising to the rank of sergeant. Deployed to the South Pacific for eight months during World War II, he injured his feet in Okinawa. For days he huddled in trenches, guarding artillery stores.

Story continuesBut in a solitary hospital bed at Jacobi, with his wife gone and his own overwhelmingly bad odds, Crouch seemed to have met a battle he couldn’t fight.Before he was stricken with COVID-19, he had lived a full life. Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Crouch first came to the city at 15 years old. He made money washing windows for a lawyer in the Williamsbridge section of the Bronx. After the war, he bought a row home in that neighborhood, and had lived there since — first alone, and later with his wife, Gail, whom he married in 1975.

They became pillars of their community. Crouch had a career as a lab technician with the City College of New York, where he taught chemistry. In the 1980s, he was voted the honorary mayor of Williamsbridge by civic leaders and worked closely with the NAACP.

“He’s always been politically active and very social,” said Adwoa-Thomas, one of Crouch’s four children.In the last week in April, Crouch’s wife became severely ill, Adowa-Thomas said, and started shaking and vomiting. George Crouch also said he did not feel well; both were transported to Jacobi Medical Center by ambulance on April 24. By April 30, Gail Crouch had died.

George Crouch became despondent after her death, and with increasingly dismal updates, his family prepared for the worst. Because of safety precautions at the hospital, they were unable to visit him. Cut off from his family, Crouch was growing isolated and dejected. The weekend after meeting Dungan, Crouch was moved to a room where he could be closely monitored and hooked up to an oxygen bag.

He was hardly sleeping and refused to eat. But Crouch brightened whenever Dungan came to visit, the captain recalled. He would pull off his oxygen mask to whisper, and they shared stories about their families and their military experience and joked about Crouch’s baldness.

“I tried to hit his room two or three times a day,” Dungan said. Often, he just sat by Crouch’s bedside as he slept.On May 5, as Dungan left their morning visit for his rounds, Crouch gave him a directive: “Rock steady,” he told him.“That term became our little thing,” said Dungan. From that morning, they greeted each other with those words and said them in parting.

Even as Crouch opened up to Dungan, he resisted medical care. He at times pulled out his IV and would not eat. He missed his wife, he told Dungan; they had been married for 44 years.When Dungan came to visit one afternoon, he nudged Crouch toward a plate of untouched food. Crouch ignored him, but Dungan persisted, he recalled.

Exasperated, Crouch pulled off his mask and glared at Dungan.“What do you want me to do?” Crouch asked.“I want you to live,” Dungan said.Crouch paused and seemed to consider the idea.“All right then,” he said, and began eating, Dungan said.Dungan, sensing a breakthrough, encouraged other military personnel working at the hospital to visit Crouch’s room over the next week. Several stopped by — lieutenant colonels, specialists, captains — and sat with Crouch.

“They helped fill in the gap for a fellow soldier,” Dungan said.The soldiers brought Crouch patches from their home units, which he began to collect. One Marine sent Crouch a “World War II Veteran” hat.The gifts raised her father’s spirit immensely, Adwoa-Thomas said. That week, he began receiving fluids and allowed nurses to insert an IV.

A week after Crouch’s condition first began improving, Dungan was alarmed when another social worker asked him to accompany her to Crouch’s room. She feared he was at the end of his life.“Once I came in there with her, he pepped back up, said ‘Rock steady,’ ” Dungan said.

He asked Crouch what he wanted to do when he got home from the hospital; Crouch told him he would “have a beer, praise God and eat some black-eyed peas.”On May 15, Crouch tested negative for the coronavirus and was released to an acute rehabilitation center, where his condition continues to improve. His family hopes he can be home soon.

On the day of his discharge from the hospital, he was wheeled through the Jacobi Medical Center lobby to raucous applause. He wore his “World War II Veteran” cap.This article originally appeared in The New York Times.