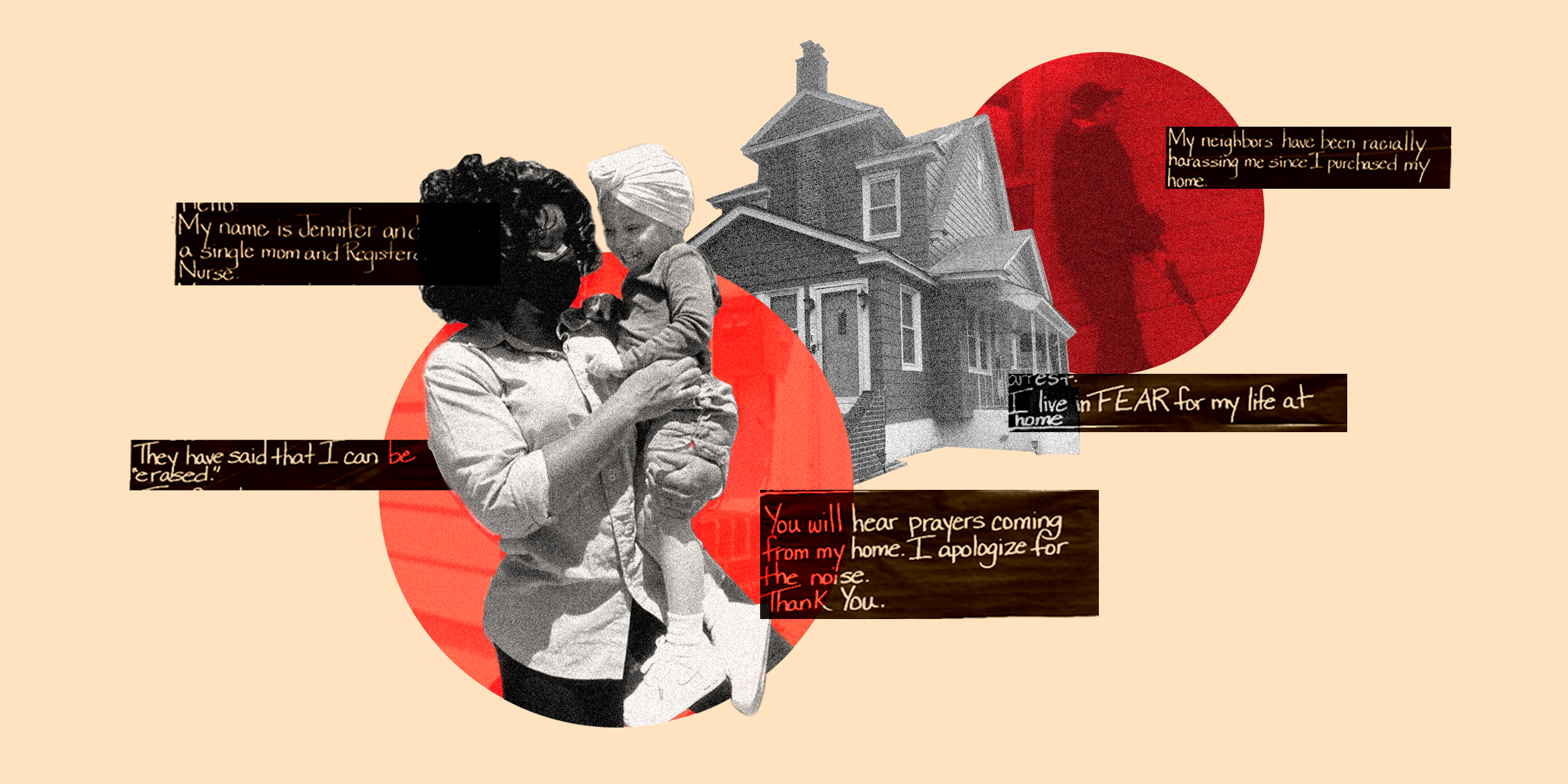

Jennifer McLeggan said her neighbors told her she could be “erased.” When she called police in her suburban New York town, she said they told her to stop calling 911.

Jennifer McLeggan, a registered nurse and single mother, worked around the clock to be able to buy a home.

“It’s hard to pay rent in New York City and come up with a down payment,” said McLeggan, who lived in a small one-bedroom apartment in Jamaica, Queens, while saving for a down payment.

“It’s not easy. I had a lot of Top Ramen nights.”

Then she happened upon the colonial-style house that she purchased in Valley Stream, a Long Island suburb of about 37,000 residents that is 27.6 percent Black. McLeggan, who is Black, was attracted in part to the town’s diversity, and she looked forward to raising her daughter in a home with a backyard.

But from the time she moved in in 2017, she said, she was racially harassed by three next-door neighbors who she said threw feces and dead squirrels in her yard. One of them also told her that she could be “erased.” She called the Nassau County police, but she said they didn’t take her complaints seriously.

In July, however, McLeggan gained national attention after she hung a handwritten sign several feet long on her front door detailing the allegations against her neighbors, who are white, and posted home surveillance video on social media corroborating some of her claims.

That captured the interest of the civil rights lawyer Benjamin Crump, who is now representing McLeggan. Crump tweeted July 14: “This type of behavior happened in the 50s and 60s to force Black families away from ‘white neighborhoods.’ It should NOT still happen in 2020.”

McLeggan’s sign also sparked a large protest in her neighborhood, inspired the hashtag #StandWithJennifer and motivated volunteers to stand guard outside her home for months. A GoFundMe campaign raised $51,000 for her. And in August, two of her neighbors, John McEneaney, 57, and his live-in girlfriend, Mindy Canarick, 53, were charged with harassing her.

Many people have questioned why it took so long for arrests to be made. McLeggan and her attorneys are among those who believe it is because she is Black. They credit the racial reckoning spurred by the death of George Floyd while in police custody in Minneapolis in May with the case’s going viral.

“The national attention that social injustices have received made it much easier for us to now bring what has been simmering for so long to the forefront,” said McLeggan’s other attorney, Heather Palmore, 49, who has lived on Long Island her entire life. “I think her courageousness literally ripped the covers off of what we already knew: that this has been going on for way too long.”

McLeggan, 39, said that the harassment from McEneaney has continued and that she feels unsafe.

She attributed the time it took for arrests to be made to the status of Black women in America.

“There’s nothing you could do to tell the truth and have the truth believed,” she said in a recent interview from Georgia, where she has retreated, about 900 miles from her home on Long Island.

A police spokesman, Detective Lt. Richard LeBrun, declined to answer any questions about the case, saying it is under the authority of the district attorney’s office “and it would be inappropriate” for him to discuss it.

‘A pattern of harassing conduct’

At a news conference July 14, the county’s police commissioner, Patrick Ryder, said that since 2017, police have received close to 50 calls from both the McLeggan and the McEneaney families, divided “almost equally,” and that all of the complaints were unfounded. He said that the dispute between the neighbors had gotten “way out of control from what it is” and that the sign on McLeggan’s door prompted police to take statements from her and her neighbors.

County Executive Laura Curran said in a statement at the time, “We take these allegations seriously, and Nassau County Police Department is conducting a thorough investigation into the matter.”

About a month later, Nassau County District Attorney Madeline Singas announced that her office had “found a pattern of harassing conduct” against McLeggan but didn’t find evidence to support a hate crime charge. The investigation “involved many interviews and a comprehensive assessment of available evidence, including video and pellet damage” to a street sign from a gun, said Miriam Sholder, a spokeswoman for Singas. A judge issued an order of protection against McEneaney and Canarick at Singas’ request to prevent future contact and harassment.

“This conduct crossed the line between being a bad neighbor and into the realm of criminality,” Singas said in a statement Aug. 17. “I was heartbroken when I saw the sign on Ms. McLeggan’s door. Nassau County is a very safe place to live, and no one should feel threatened in their own home.”

McEneaney was charged with criminal mischief and harassment. He is accused of repeatedly shooting a pellet gun in “a dangerous way” across McLeggan’s lawn from April 2017 until July 2020, striking a nearby street sign at least 20 times, “allegedly as a form of harassment to annoy or alarm her,” the district attorney’s office said. At least four pellets were found on McLeggan’s lawn.

Canarick is accused of dropping feces on McLeggan’s lawn and was charged with criminal tampering. All three charges are misdemeanors. Both have pleaded not guilty. McEneaney’s attorney, Joseph Megale, and the Nassau County Legal Aid Society, which is representing Canarick, declined to comment.

Before his arrest, McEneaney told NBC News that he isn’t racist and denied any wrongdoing. His attorney at the time, Jason Kolodny, said he felt that McEneaney was a victim “of this country’s long history of racism against African Americans.”

McLeggan, who installed her first home surveillance camera in 2018, provided authorities with videos that Singas alleged showed feces being thrown on McLeggan’s lawn, among other things.

Valley Stream, just east of New York City, is among the more diverse communities on Long Island, with a population that is 41.8 percent white, 27.6 percent Black, 22.9 percent Hispanic and 15.4 percent Asian. (Some residents identify as more than one race.) The Nassau County police force is predominantly white. Of the county’s 2,290 officers, 1,979, or 86 percent, are white. According to the most recent census data, nearly 1.36 million people live in Nassau County, 73.1 percent of whom are white.

McLeggan said the harassment started when she moved into the home on Sapir Street in the spring of 2017. Her neighbors asked her what her plans were for cleaning up the property and requested that she cut down trees, she said.

“I did feel overwhelmed, because I was working full time and I was pregnant,” she said. She hadn’t even begun unpacking, and around the same time, her boiler broke. “So I was just trying to focus on the inside of the house first and then get to the outside,” McLeggan said.

The harassment began when litter, feces and dead squirrels were thrown on her property, and it escalated to racist threats and to McEneaney’s shooting targets in his backyard, she said.

McLeggan said that McEneaney told her she could be “erased” and that his father, Michael, told her to go back where she came from, which she interpreted to be racist. “What would that mean if it was not related to race?” she asked.

McLeggan said that in the summer of 2019, she called the police after she heard loud popping noises, which she described as a regular occurrence, from McEneaney’s shooting what she would later learn was a pellet gun in his backyard and onto her property. She said that she believed the gun was a long rifle and that she feared for her safety and that of her 2-year-old daughter, Immaculate. She said they didn’t use their yard for months. McLeggan said that when she told all this to a responding officer, she was instructed to stop calling 911 and to try to get along with the McEneaneys because they had lived in the neighborhood for decades.

“So I stopped calling,” McLeggan said.

McLeggan said police also told her that she couldn’t obtain a restraining order against her neighbors unless she had been harmed. Typically, obtaining an order of protection requires an offending person and a victim, or a district attorney can request one from a judge. Police declined requests for comment about McLeggan’s account of events.

In 2019, McLeggan said she provided a judge with video evidence of Canarick’s throwing dog feces on her property and won a judgment in small claims court against Canarick for $5,036.24, which went unpaid.

“I never pressed Mindy for that judgment,” McLeggan said. “Because I just wanted her to get the message to leave me alone. But it got worse after that judgment.”

The previous owner of McLeggan’s home, who is West Indian, said that she had minimal interactions with John McEneaney and Canarick in the 25 years she lived there but that she did observe Michael McEneaney trapping and drowning squirrels on his property. The previous owner, who asked not to be identified out of concern for her job, said that while she never saw him throw any on her lawn, she did often find dead squirrels buried or otherwise visible on her property.

The former owner said that for many years, she had a great relationship with the elder McEneaney but that their friendship soured in 2011 after Hurricane Irene, because he claimed that branches from a tree from her yard had scratched his vehicle and demanded that she give him $500. After she asked him to show her evidence of the damage, he refused, she said, so she didn’t pay him.

She then began to find long nails in her tires, and the sideview mirrors on her cars were broken on separate occasions. She said that while she suspected that the elder McEneaney was responsible, she could never prove it, and that when she called the police, they told her there was nothing they could do without evidence. Nassau police didn’t return a request for comment about her account.

Attempts to reach Michael McEneaney by phone and at his home were unsuccessful.

‘We know now that there is a big problem’

Palmore, a former prosecutor who previously worked for the Queens district attorney’s office with Singas, said, “Long Island is that place where people come to live out the American Dream.”

Many people leave the city to live in the suburbs to have access to beaches, good schools and parks, she said, but they lack an understanding of the divisive racial history behind Long Island.

The school district in Malverne, which is near Valley Stream, was the first in New York to come under a desegregation order, Palmore said.

Elaine Gross, president of the Long Island organization ERASE Racism, which offers educational workshops on unraveling racism, said students aren’t taught about Long Island’s racist history. For example, the initial leases in Levittown in Nassau County, widely recognized as one of the first post-World War II suburbs, explicitly stated that its homes were to be used or occupied only by Caucasians.

“They don’t learn about the federal government and its redlining policies and its policies of having racial covenants in the deeds,” Gross said.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants couldn’t be enforced, but such covenants continued. To date, Black people account for 1.2 percent of Levittown’s population.

A three-year investigation of Long Island real estate agents published last year by Newsday revealed widespread housing discrimination against Black people and other minority groups. The newspaper’s investigation showed that “Long Island’s dominant residential brokering firms help solidify racial separations” by steering minority customers to majority-minority areas and by directing white customers toward mostly white neighborhoods, the newspaper reported.

Gross said she believes the Newsday investigation made it hard to deny that racial discrimination persists on Long Island.

“No one could with a straight face say, ‘Oh well, it was just a couple of bad apples,'” she said. “It really showed what was going on in the industry. We know now that there is a big problem.”

What McLeggan experienced “has been going on for decades,” said Palmore, who is Black, adding that many Black people have been silent because they’re so used to it. She credited the Black Lives Matter movement with emboldening people to speak out against injustices.

Gross said it can’t be overlooked that President Donald Trump has been accused of stoking hatred, divisiveness and racism over the last four years. “And that creates an atmosphere where you can have white people feel that they can do whatever they want to do and get away with it,” she said.

(Trump has denied being racist. During the final presidential debate last week, he claimed to be “the least racist person in the room.”)

Gross mentioned Amy Cooper, a white woman who called police and falsely claimed that she was being threatened by a Black bird-watcher in Central Park who had asked her to leash her dog in an area where it was required. A video of the encounter, recorded by the bird-watcher, has been viewed more than 44 million times. Cooper has been charged with filing a false police report. A day after the incident, she issued a public apology.

Gross said people need to treat racism like the cancer it is.

“We know that racism is a vicious and deadly thing. But it is not treated like that. It’s treated as if it’s benign. And it’s never benign,” she said. “Maybe it doesn’t go to the extremes of what Jennifer had to undergo, but it’s never benign. It’s always harmful. And it’s harmful to the individual and to their families. But it’s also harmful the way that it poisons society.”

McLeggan said she is deeply hurt by everything that has happened and that she is uncertain whether she wants to return to Valley Stream.

“The sign went up, and I didn’t expect for it to go viral,” she said. “I just said, ‘What else was I going to do at this point?’ You can’t call the police. No one is really helping you. So what can you do?”