High-risk students in states and districts that have made masks optional are staying home.

When the coronavirus first swept across Florida last year, Angela Gambrel did everything she could to lock down her home in Sumter County, northeast of Tampa.

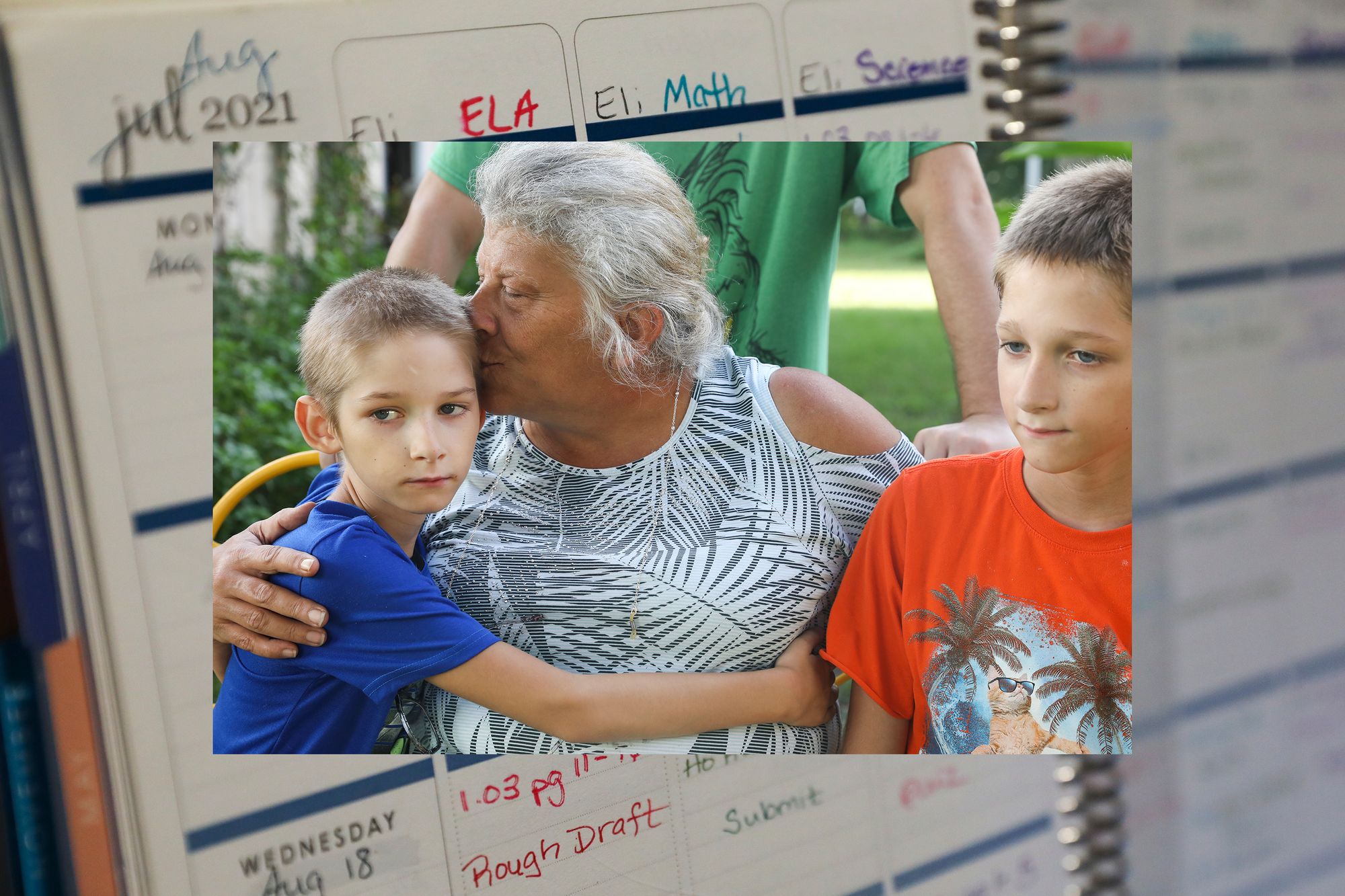

Her 10-year-old grandson Jayden has a rare brain disease that disrupts his immune system and impairs his memory, making it harder for him to process complex tasks. His doctors urged her to take every possible precaution against the virus. No more supermarket runs. No more football scrimmages with his Special Olympics team.

Jayden’s school, like others across the state, halted in-person instruction, distributing worksheets to students to complete at home. The only time Jayden was around other people was when he had bloodwork done or underwent his monthly treatment about an hour away at Tampa General Hospital.

When schools reopened last fall, Gambrel, who’s been Jayden’s guardian since he was a toddler, kept him and his brother home, unwilling to risk exposing Jayden to a virus the world was just beginning to understand.

But without the intensive in-person instruction that he had been receiving for years, Jayden struggled, unable to keep up with his coursework.

Watching him languish, Gambrel knew he needed to go back to school as soon as it was safe, and so she was relieved to hear last month that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was advising school districts to have students and teachers mask and socially distance and to vaccinate staff. Jayden, she thought, could finally go back to school in person.

But a few days later, her plans were scuttled by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, who imposed a statewide ban on mask mandates in schools. Without assurances that all the students in Jayden’s school would be masked, Gambrel decided she could not take the risk of sending him back to the classroom.

“If they could just require masks, then these boys could have a life,” Gambrel said.

As children have begun returning to classes this month in many parts of the country, the delta variant has dashed hopes of restoring something approaching normal life, upendingschool reopening plans everywhere and reigniting bitter fights over masking and other public health precautions.

For families whose children are too young to be eligible for vaccinations, the delta surge has once again left many parents weighing the risks of in-person learning, especially in states that are bucking federal recommendations to impose universal masking in schools. Some families have reluctantly shifted back to virtual instruction. Others have pulled their children out of the public school system altogether, opting for home-schooling.

But for families like the Gambrels, the stakes are exponentially higher. Children like Jayden, with complex health conditions, often are among those most in need of direct, specialized instruction that can only be delivered in person. Those same health conditions can also put children like Jayden at higher risk of infection and illness.

Nationwide, about 7.3 million students have significant disabilities that impact their education. About 15% of these students receive special education services for health conditions that limit their ability to learn, which include common conditions like diabetes, asthma or epilepsy, as well as rare disorders.

COVID-19, of course, is a new disease and researchers are a long way from fully understanding how it affects people with underlying medical conditions, especially children, who in the first waves were less likely to be sickened by the coronavirus. But the CDC says the “evidence suggests that children with medical complexity, with genetic, neurologic, metabolic conditions, or with congenital heart disease can be at increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19.”

Chronic diseases affect millions of children nationwide. For example, more than 6 million kids suffer from asthma, over 200,000 live withType 1 diabetes and more than 14 million are obese.

For medically vulnerable children, schoolwide masking is essential to allow them to safely return to school, health experts say. And being forced to stay at home while other students are able to learn in person could run counter to federal education law, which prohibits children like Jayden from being unnecessarily isolated because of their disabilities.

“All people with disabilities should receive services in the most integrated setting appropriate,” said Ron Hager, managing attorney for education and employment at the National Disability Rights Network. “If not for the mask mandate, these kids could be educated in the most integrated setting.”

With infections surging among children just as they are returning to classes, the fight over mask mandates is intensifying. Parents and civil rights groups have launched legal challenges against mandates in several states. Administrators in some school districts are ignoring state bans and imposing universal masking. And in Washington, President Biden has decried the politicization of public health measures like masking and directed his administration to ensure that state officials are taking the necessary steps for students to safely return to the classroom.

The administration has sent letters to eight states that have blocked mask mandates — Florida, Texas, Tennessee, Iowa, Arizona, Utah, Oklahoma and South Carolina — to tell them their policies violate “science-based strategies for preventing the spread of COVID-19,” and the Department of Education said it may open civil rights investigationsin states that block universal masking.

“We are not going to sit by as governors try to block and intimidate educators protecting our children,” Biden said last week at a White House news conference.