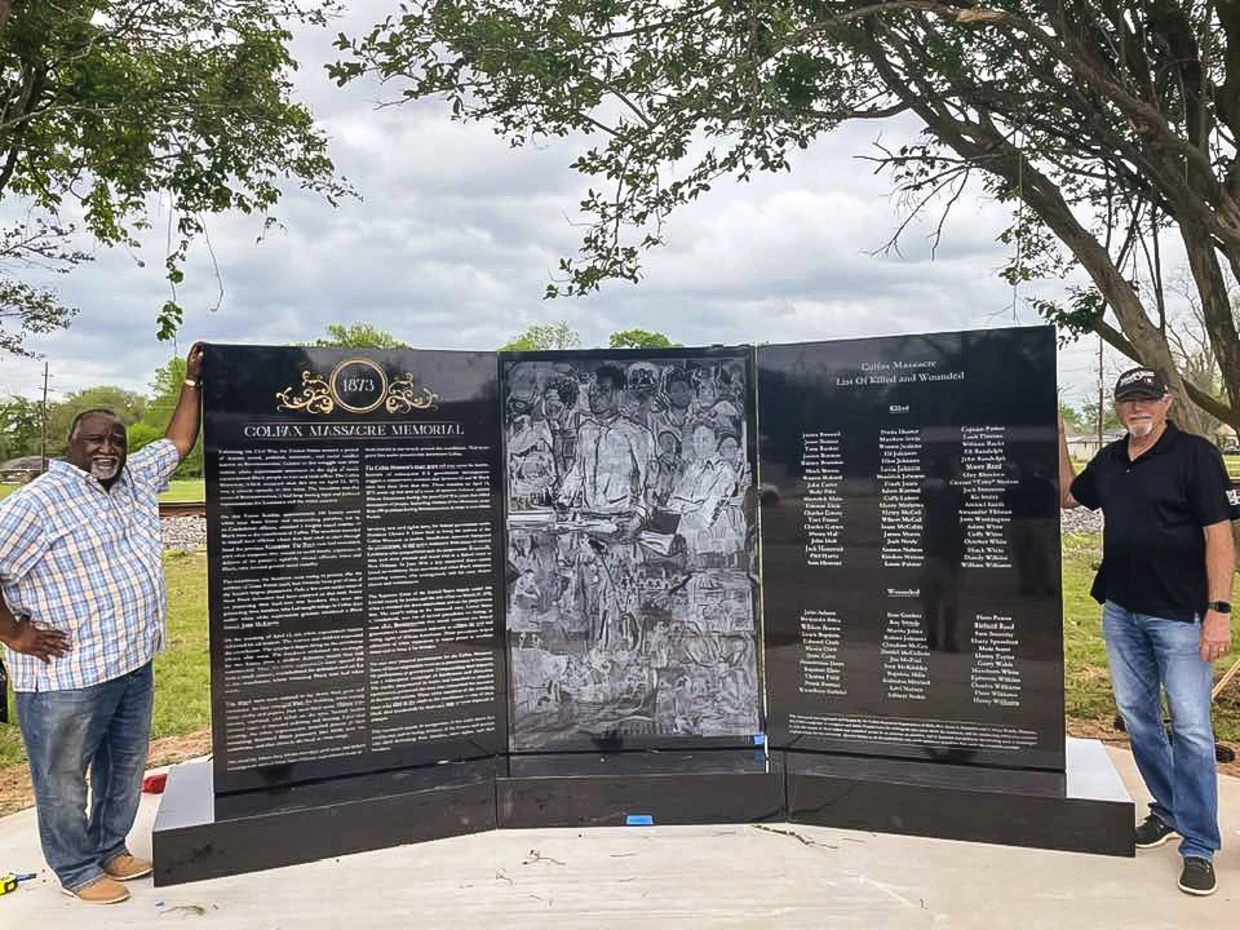

The new memorial lists the names of 57 Black people killed in the Colfax Massacre in 1873.

Exactly 150 years after a violent massacre left dozens of Black people dead, the small Louisiana town where it happened is honoring its victims with a new memorial replacing a racist historical marker.

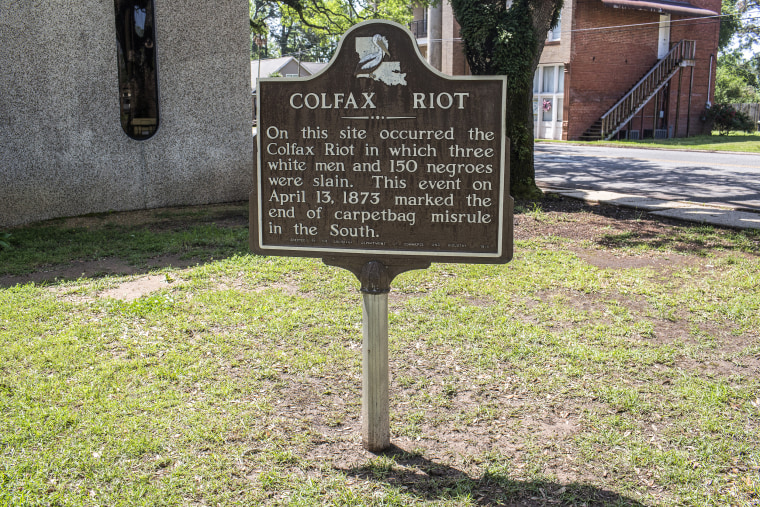

The original marker was placed near the Grant Parish Courthouse in Colfax, Louisiana, in 1951 to document a violent confrontation between newly emancipated Black voters and white Confederate sympathizers in the town. It called the killing of dozens of Black people a “riot” that “marked the end” of misrule in the South. That marker, which also honored three white men who died, was torn down in 2021 and was replaced Thursday with a 7-foot granite monument on the 150th anniversary of the Colfax Massacre.

Avery Hamilton and Charles Dean Woods, leaders of the Colfax Memorial Organization, led an initiative to erect the monument, which lists 57 Black people identified in the mass killing by the racist mob on April 13, 1873. It also features artwork reflecting the Black experience during Reconstruction by Jazzmen Lee-Johnson, a Black visual artist.

Woods said he felt both shocked and ashamed after learning about his great-grandfather Bedford E. Woods’ involvement in the massacre. This prompted him to work with city officials to get the original sign removed in May 2021.

“I was just like, ‘What do I do about this?’” Woods, who lives in Houston, said. “And when I finally found out about the marker being there, I went to Colfax and saw it in person and just, you know, tried to figure out what to do.”

Hamilton and Woods said outsiders and many residents have little knowledge of the massacre, which is why they aim to use the monument to educate others about what happened that day.

“It’s never too late to tell the truth,” Hamilton, a Colfax resident, said.

The truth begins with the killing of Hamilton’s ancestor, Jesse McKinney, on April 5, 1873.

“There was a band of whites, 10 to 15, rode up on my great-great-great-grandfather who was on his farm, mending his fences,” Hamilton, 57, said. “And they rode up on him without a word or warning and just shot him. And his wife and their children witnessed this.”

The unprovoked killing aroused fear in Colfax’s Black residents, prompting them to seek refuge together at the courthouse.

At the same time, white residents spread rumors accusing Black people of rioting. On April 13, 1873, Easter Sunday, Black men guarding the Grant Parish Courthouse were attacked by a mob of white men, who ultimately killed an estimated 57 to 80 Black people.

Federal troops arrested several white men in connection with the massacre, and nine were charged in the case U.S. v. Cruikshank. Ultimately the Supreme Court ruled in the men’s favor in 1876.

The massacre was one of many instances of racial terror that tore through the South to continue the oppressive hierarchy established by slavery, which had only been abolished seven years prior, Woods said.

“The impact on Black Americans was much more than those 57 to 80 people that were killed,” he said. “It was on millions and millions of African Americans who were denied their rights until the early ‘60s. And even now, we still have struggles in America with people who don’t provide equal rights to all men.”

The Colfax Massacre also resulted in the continued disenfranchisement of many Black residents, further preventing them from having a political voice, said Hamilton, who is the pastor of the First Baptist Church in Colfax. Hamilton’s father, Tom Hamilton Jr., was the first Black person in Colfax to run for mayor, in 1978, he said. While his father lost that election, Hamilton said he did eventually become the first Black person elected to the municipal board known as the Police Jury in Grant Parish, where Colfax is based, in 1982. Hamilton’s brother, Gerald Hamilton, became Colfax’s first Black mayor in 2014.

Before his father, “there were absolutely no Blacks in any political position in Colfax, ever,” Hamilton said.

Donors raised approximately $65,000 to build the new monument, Woods said. While there is a memorial in town honoring the white mob members, there was nothing that honored the memories of the Black men who were “fighting for their right to exist,” Hamilton said — until now. The new memorial names 57 Black men who were confirmed fatalities from the massacre, but Hamilton said there is “no doubt” more were killed.

With the new memorial, Hamilton said he wanted to honor the men and what they died for. Upon learning of his efforts to build the new memorial, some people have asked him, “Why not leave it alone?” His response: because “now is the time.”

“‘Why now’ is because my grandmother couldn’t do it,” Hamilton said. “My great-grandmother couldn’t do it. They didn’t have the political power. They didn’t have the means, the money, the muscle to do what we are doing now. What we are doing today couldn’t have been done 50 years ago.”

For Woods, this new memorial not only inspires him but future generations, including his Black 7-year-old granddaughter, whom he wants to have the opportunity to excel and be treated equally, he said.

“We can’t just sit back and talk about things; we have to act and move the needle forward on justice for all people,” Woods said, “regardless of race or ethnicity or national origin. And these are things that I want people who hear about this story to recognize and to examine in their own lives and their own hearts.”