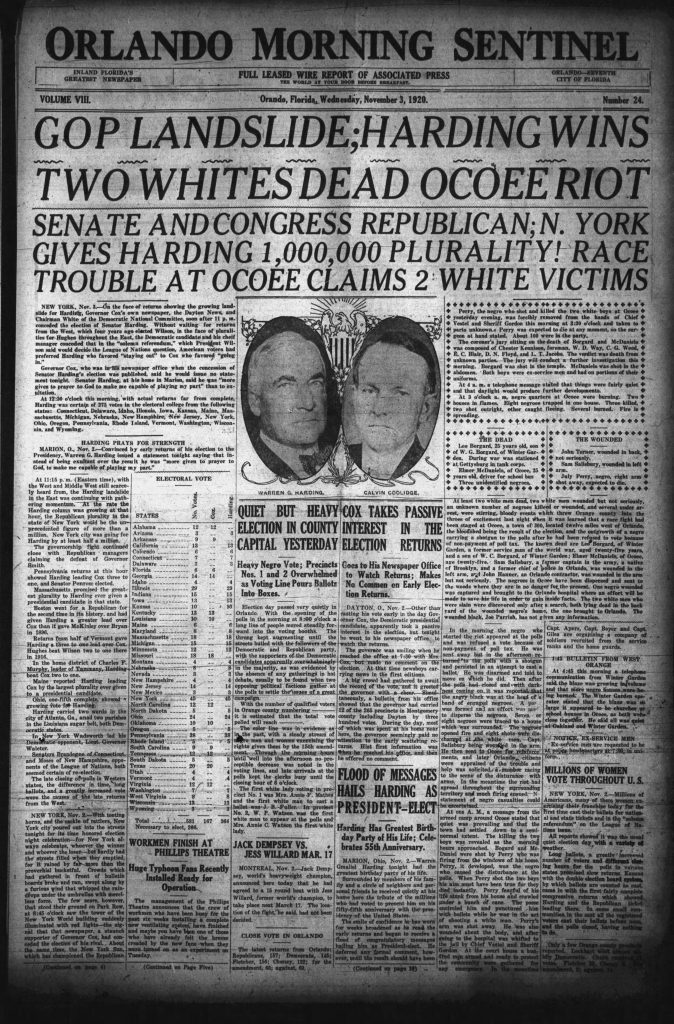

As was generally the case with lynching, the medium itself was the message. And if that wasn’t enough, there was also a sign. The note that the white mob attached to the dead body of Julius “July” Perry reportedly read:

“This is what we do to n****** who try to vote.”

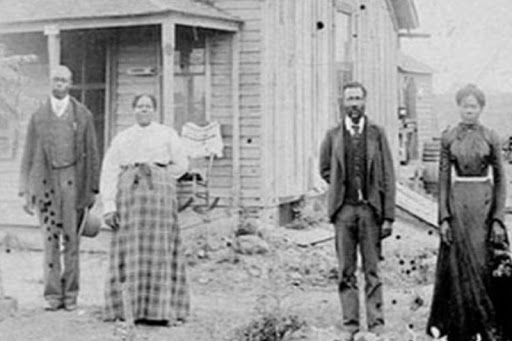

Hours before, Perry had been a prosperous Black landowner, a labor leader, a church deacon and a respected member of his community living out the American Dream amid the orange tree groves and sugar cane fields of Central Florida. Then, a century ago on Nov. 2, 1920, Election Day, Perry’s prosperity and the thriving existence of the Black neighborhoods of his hometown of Ocoee came to an abrupt halt.

Perry’s lynching was just the start: the white men responsible for it shot, injured and killed dozens of other Black residents, including children. They burned their houses and churches to the ground. Almost the entire Black population, up to 500 people, fled the town, abandoning their homes and possessions, never to return. The Ocoee massacre remains the worst incident of election violence in U.S. history, and the forgotten — and intentionally buried — story of how one small-town community’s exercise of its constitutional rights transformed into an episode of unthinkable racial cleansing still has the power to shock a century later.*****

Ocoee, now a town of almost 50,000 people located approximately 10 miles west of Orlando, was founded in the 1850s. But today its Southern charms, and tranquil locale, alongside the pristine Starke Lake, conceal a horror that the area is still coming to terms with today.

Florida was once a sanctuary for African Americans. Way back in 1693, King Charles II of Spain freed the nation’s ex-slaves, and the St. Augustine area became a haven for runaway slaves from the British colonies. Eventually Spain relinquished Florida to the British, those colonies came under the United States and slavery returned to Florida — the federal government under Thomas Jefferson deploying its own soldiers to return many of the area’s Blacks to bondage.

Following the Civil War, slavery was abolished, but segregation, white supremacy and voter suppression reigned. In addition to acts and threats of violence, Florida’s white leaders used poll taxes, grandfather clauses and voter “qualification tests” containing absurd questions like “How many bubbles are there in a bar of soap?” to render Black suffrage as meaningless as possible.

But in 1920, empowered and inspired by the 19th Amendment’s recognition of women’s right to vote, Black Floridians began to organize as never before — voter registration drives, marches, secret voter education workshops at churches and lodges. The grassroots democratic effort formed what Paul Oritz, historian and author of Emancipation Betrayed, calls “the first statewide civil rights movement in U.S. history.” But the powers that be did not care for it. “There is a statewide reactionary movement against the Black struggle to regain the right to vote,” says Ortiz. “And the Ku Klux Klan was one part of that movement.”

The KKK staged large marches in Jacksonville, Daytona and Orlando designed to intimidate voters. They even turned up in what was then a small citrus town of about 1,000 people, Ocoee, on the evening before the Nov. 2 election, shouting into megaphones that “not a single Negro will be permitted to vote.” And that was not hyperbole. On Election Day in Ocoee and elsewhere in Central Florida, armed white deputies stood guard as self-declared poll monitors. Poll workers routinely challenged Black voters, who could only contest those challenges before the local justice of the peace, who had — conveniently, and by design — gone fishing that day.

One of the Black citizens who was turned away from the polls that day was Mose Norman, a 59-year-old farmer and businessman who owned a 100-acre family orange grove and a six-cylinder Columbia convertible. Like his friend July Perry, he was a pillar of the Black community in Ocoee, and one of its most politically active leaders. With no means of redressing the voter suppression in Ocoee, Norman traveled to Orlando to seek the help of Judge John Cheney, a white Republican running for the U.S. Senate and a supporter of Black voting rights. Cheney asked Norman to return to the polls in Ocoee and start gathering information, including the names of the individuals who were preventing Blacks from voting. This was likely for the purpose of filing a complaint or a lawsuit, but it proved to be a very dangerous errand.*****

Norman returned to Ocoee. There are conflicting accounts of exactly what happened next, but it appears that armed men drove Norman from the polls and he fled to the nearby home of July Perry. Rumors then began to swirl among whites in Ocoee that Blacks with guns were assembling in Perry’s home, and a group of 20 or more heavily armed white men led by Sam Salisbury, a former Army colonel and former Orlando Chief of Police, were deputized by the Orange County Deputy Sheriff to investigate.

Salisbury, with the mob behind him, knocked on July Perry’s front door and demanded his surrender. A scuffle ensued during which Perry’s daughter fired a shot that hit Salisbury in the arm. This set off a shootout at the house in which at least two white men were killed. The mob would later claim that “37 armed Negroes” participated in the shootout, but it is more likely that it was Perry, his wife, daughter, sons and a couple of hired hands that held off the large mob. Mose Norman had already fled Ocoee in his convertible and was never seen again.

The mob set Perry’s house and barn on fire and his family escaped into the woods. July Perry was captured in a sugar cane field near his house and shot several times. He was taken to the local jail as news of the shootout spread. Alerted by an electronic signboard in Orlando that was being used for the first time to broadcast election returns, hundreds more white vigilantes from across the county descended on Ocoee. Perry was taken from the jailhouse at 3:30 a.m. by a mob of around a hundred white men. They drove him to Orlando and lynched him from a big oak tree outside the entrance to the Orlando Country Club, a tree visible from the home of Judge John Cheney.