At the age of 6 and 36, Duana Johnson’s disappearances — attempts by predators to traffic and prostitute her in the Washington state area — could’ve led to her being an unfortunate and all-too-common statistic of missing BIPOC women who end up murdered.

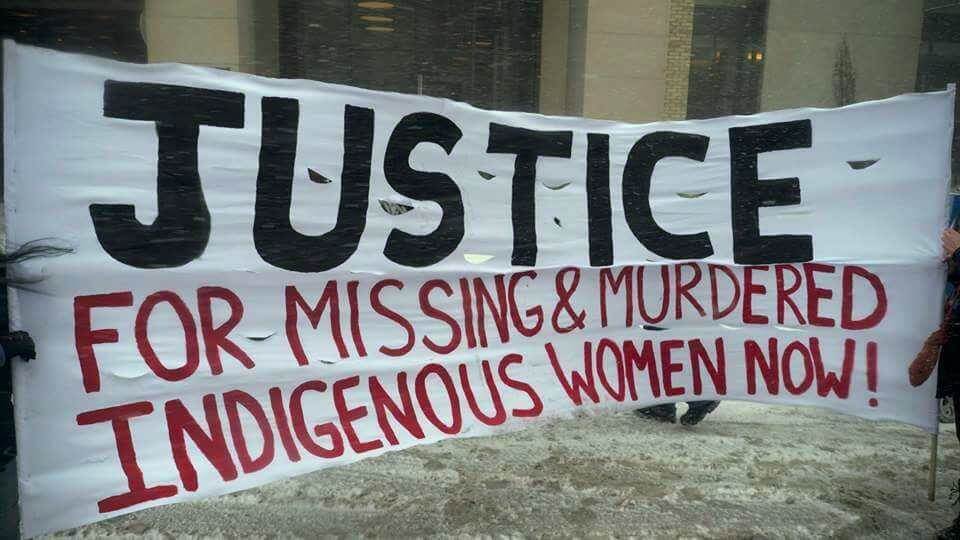

Johnson says sometimes it feels like no one, including law enforcement, bats an eye or raises a flag when an Indigenous woman or girl goes missing.

“How many of them have asked ‘are they looking for me’ or does my life matter if I’m missing,” said Johnson. “This isn’t new. This has been happening to our women for decades, centuries — but now we’re starting to see people pay attention.”

In February, Congress held a two-hour hearing to address what they call a “silent epidemic” of missing Black, Indigenous and women of color (BIPOC) and their overrepresentation in the nation’s missing person cases.

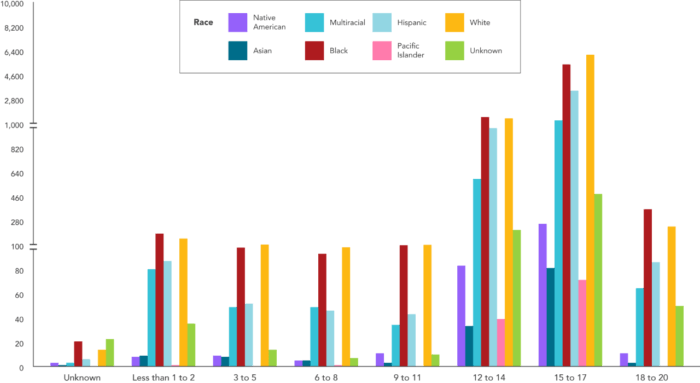

According to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database, there are more than 424,000 missing children in America. In 2020, 40% of all women and girls reported missing were people of color — 100,000 out of 250,000 — despite making up just 16% of the population.

“I spoke to sheriffs’ departments about my situation, about others and you feel invisible, forgotten, ashamed and blamed,” Johnson told the Bronx Times. “We are conditioned to act and not bring attention to ourselves when you’re being trafficked like that. And when you’re so beat down to the point of where you want to make yourself small and invisible, it’s hard to unlearn that and find your voice.”

Johnson, now 57, dedicates her life to the missing and murdered Indigenous women — like Amy Lynn Hanson and Sherry Ann — whose stories are either untold or have been largely neglected and ignored by law enforcement and the media.

“We have seen so many of our sisters go missing. So many of our stories (when we go missing) end in violence, and mine luckily didn’t. It took me a while to realize that our lives weren’t a priority,” said Johnson. “There’s crickets when women of color go missing, and I know how scary it is for these women and girls, and I want to … keep them safe and find those who are still missing.”

There is no definitive estimate of the number of adults who go missing, because some adults are not known to be missing or are not reported to databases that compile data on missing persons. And advocates for organizations dedicated to addressing the disparities in missing BIPOC women and girls, say that federal data can often be unreliable and undercounted.

In 2016, the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center noted that 5,712 cases of missing Indigenous women and girls were reported, but only 116 of them were logged into the Department of Justice’s database.

Advocates say law enforcement has long misunderstood and failed to track tribal missing-women cases, as well as misidentifying victims whose ethnicity isn’t obvious and whose family names may be confusing or misleading. In some cases, according to testimonies in Congress, there is little to no data on missing Hispanic or Latino women, as their cases are captured under the “white” demographic.

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), a national task force established by Congress in 1984 gathers data directly from law enforcement as children go missing, while FBI data is reported annually via NCIC.

Sherri Jefferson, the executive director of the African American Juvenile Justice Project (AAJJP), says that data on the nation’s missing and murdered Black girls and women is also unreliable.

Jefferson believes systemic inequalities and lack of transparency and accountability by law enforcement and prosecutors in cases involving Black children plays a part in this silent epidemic.

“Our children and young adults are often adulterated and are less likely seen as victims,” said Jefferson in a November 2021 interview. “Black, African American and Afro Latinas are less likely seen as victims of kidnapping or missing by force or coercion. Instead, they are perceived as willing participants engaged in sex for profit or runaway.”

Lawmakers like Illinois U.S. Rep. Robin Kelly, a Democrat, warned that implicit bias and misconceptions of hyper-sexuality and truancy among Black girls downplay instances when they are sexual assaulted, trafficked and prostituted.

According to the FBI, 53% of all “juvenile prostitution” arrests are Black children, but Kelly notes that there is no such thing as “juvenile prostitution” — juveniles cannot consent to sell sex — therefore it is not being treated as sex trafficking by law enforcement and federal agencies.

Invisibility from law enforcement and missing white women syndrome

When Gabby Petito went missing in July 2021 — and was ultimately killed by her fiancé, Brian Laundrie, while they were traveling together on a cross-country van trip — it galvanized the national media. Her story has also been the subject of several documentary series, a nighttime special and even a Lifetime movie.

The Petito case — and widely-publicized missing persons cases such as the 2005 disappearance and death of Natalee Holloway — highlights the disparity in police resources and media attention often focused on missing white women compared to missing people of color.

“The big national media outlets, you know, when a white girl goes missing, it’s on every day pretty much, and the troops are rallied and they say ‘let’s go find her,” said Johnson. “When a Black or Indigenous woman is missing, it’s never treated with that same urgency or care.”

In Wyoming, the state where Petito went missing, 710 Indigenous people were reported missing in the past decade, according to a report this year by the University of Wyoming. The report also found that 85% of the missing were minors — 57% women and girls — and that Indigenous people were about 100% more likely than their white counterparts to still be missing after 30 days.

For a host of reasons, the problem is vastly underreported, said Johnson, the victim of two instances of kidnapping. Reservations and rural areas can be internet and telephone service deserts which greatly impact timely crime reporting and data gathering.

At the Feb. 28 congressional hearing, Pamela Foster, a member of the Navajo tribe in New Mexico, detailed the tragic events that led to the brutal abduction and murder of her children, 11-year-old Ashlynne Mike and nine-year-old Ian. Her testimony grippingly singled-out the slow response and lack of preparation from tribal law enforcement as failings in any effort toward her children’s recovery.

BIPOC women also experience higher rates of intimate partner violence than white women, and Indigenous and Black women experience the highest rates of sexual and physical violence of any demographic group.

In HBO’s documentary series “Black and Missing,” produced by Geeta Gandbhir and longtime journalist-activist Soledad O’Brien, missing cases involving Black people take four times longer to resolve, with that additional time also increasing the difficulty in conducting adequate investigations.

Advocates say crucial mistakes by law enforcement such as labeling these disappearances as runaways exacerbate this silent epidemic.

According to Natalie Wilson, the founder of the Black and Missing Foundation, 9 out of 10 children of color reported missing are classified as a runaway by law enforcement which prevents an AMBER Alert from being issued thus providing little to no media coverage and less police and government resources.

“A lot of minority children are initially classified as runaways, and as a result do not receive the Amber Alert, which is a crucial life-saving tool,” said Jefferson, the executive director of AAJJP. “Harmful attitudes that believe that because these missing minorities live in impoverished conditions and crime is a regular part of their lives, they are criminal and runaways, desensitizes us to their disappearances.”

What needs to be done

When John Bischoff — vice president for the Missing Children Division at NCMEC — testified in front of Congress, he was surprised yet optimistic about lawmakers’ interest in addressing this troubling trend.

“It was just amazing that they wanted to hear about this issue. It’s big enough in Congress’ eyes that they were having a hearing about it to just get more information, to figure out what route we need to go to fix this.” said Bischoff. “Every state is taking a look at this issue. What I’m hoping to see is which piece of legislation is gonna be most impactful for the issues that we’re seeing today as a society.”

There’s a slew of action, advocates say, that Congress can take to make headway into addressing disparities for missing BIPOC women and girls.

Among those, Congress could reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act and Frederick Douglass Trafficking Victims Prevention and Protection Reauthorization Act of 2021, pass the Protect Black Women and Girls Act and fund the full implementation of the Ashanti Alert Act.

Of New York state’s 606 current list of missing persons, 11 reside in the Bronx, with nine being BIPOC girls. And according to the most recent state data on missing persons, the largest single group of missing children cases involves Black females, ages 13 and older (29.2% of all cases reported).

Bronx City Councilmember Althea Stevens has proposed legislation to create a task force to look into the city’s missing BIPOC women and girls. A similar bill in the state Senate says a statewide task force is necessary to prompt more urgency among law enforcement when BIPOC women and girls go missing and to prevent those cases from being labeled as runaways.

Bischoff said that local task forces will need to be proactive in their approach, such as debunking long-held myths about missing persons cases such as families have to wait 24 hours for someone to be missing before law enforcement can act.

“That’s an older misconception by many families across the United States that they have to wait 24 hours or 36 hours or a certain hour range before they can report someone missing — and that’s not true,” said Bischoff. “Every missing persons case is unique and individual but every second counts, and it takes every bit of effort on a local level to help find them.”

Reach Robbie Sequeira at rsequeira@schnepsmedia.com or (718) 260-4599. For more coverage, follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @bronxtimes