A National Truth Commission for Native Americans, similar to efforts in other countries to examine historical legacies of abuse and discrimination, can help restore dignity to indigenous populations in the U.S., according to a paper in the Wisconsin Journal of Law, Gender and Society.

The commission would open “a significant pathway towards healing for centuries of genocide committed against one of the most disenfranchised groups in the United States,” wrote the author of the paper, Sara Ochs, an assistant professor at the University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law.

It would be designed to lay a foundation for addressing the ongoing harms that have been a consequence of both government and individual actions since the settling of the North American continent, Ochs wrote.

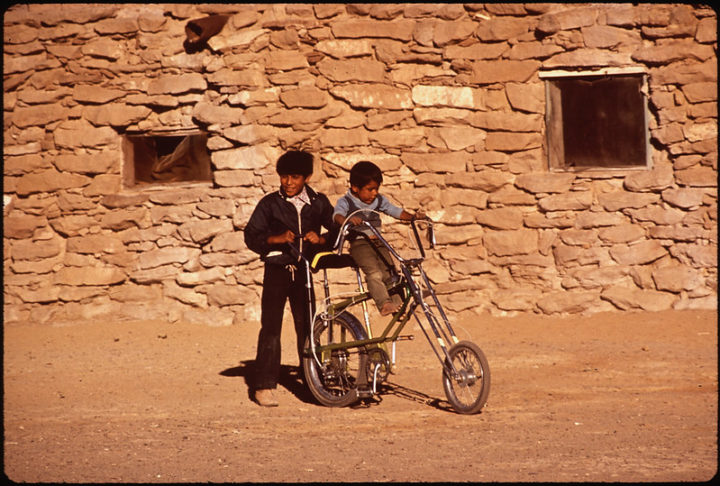

Those harms stretch from the historical legacy of forcing native children into government schools where they were prohibited from speaking their language to the present day’s litany of physiological and psychological damage that has led to high rates of poverty, as well as alcohol and drug abuse.

“A national truth commission could bring the dark history of human rights abuses against Native Americans into the public realm,” Ochs wrote.

Citing Laurel Fletcher, a clinical professor of law at UC Berkeley and an authority on truth commissions, Ochs said such bodies offered a form of transitional justice that allows the descendants of victims and perpetrators to start a healthy dialogue.

One recent example in the U.S. was the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, created in 2012. The three-year-long commission documented abuses against indigenous Wabanaki people who were forcibly removed from their lands and whose children were sent to boarding schools to “kill the Indian in them to save the man.”

Canada, Greenland and Norway have held similar truth commissions on a national stage, which resulted in both reconciliation and government funding of new programs focusing on helping the descendants of aboriginal peoples reassert a dignified place in their societies.

Post-apartheid South Africa conducted a similar Truth and Reconciliation Commission that ended in 1998 and received mixed reviews. Although many welcomed the opportunity to air the abuses suffered under 43 years of apartheid, others criticized the decision to provide amnesty to individuals who had committed abuses in return for their testimony. Some 2,000 people testified at often-emotional hearings conducted in various cities.

Ochs said her proposal similarly would not seek criminal accountability of “traditional justice” for acts committed against indigenous peoples, partly because many of the perpetrators had long since passed from the scene and also because many of the harms were the result of direct government policies since the settling of the North American continent.

Instead it would serve as a channel for Indigenous voices that have been long silenced, she wrote.

“Providing this level of healing and trauma relief at a national level could produce profound results in Native American communities throughout the country,” Ochs added.

Federal support and funding would be required for a U.S. commission, not only to support the cost of mounting hearings in often-hard-to-access regions of the country, but to ensure participation of members of the multiple Native American tribes at all levels of the Commission, Ochs said.

Ochs said full participation of indigenous people was critical.

“Victims must not only participate in transitional justice, but also help to create, craft, and operate the initiative, so as to ensure it aligns with their expectations,” the report states.

The report says it is essential for people to provide testimonies and witness statements in public because it holds enormous potential for healing and trauma recovery, both on an individual and community level. Public hearings will be a huge factor in the success of the commissions, the report states. Fact-finding objectives also benefit from a public commission.

Ochs’ paper comes as the country confronts an epidemic of missing indigenous women, many of them the presumed victims of sex crimes and sex trafficking, and calls for authorities to devote more resources to a problem that many native critics charge has been neglected.

Indigenous communities across the American Southwest, top government officials, family members and advocates gathered last week to issue a “call to action” to address the ongoing problem of violence against Indigenous women and children.

1,500 Missing Native Women

Federal statistics that show at least 1,500 Native Americans and Alaska Natives are missing and Native women are at an increased risk of violence. While federal figures show that Indigenous women — along with non-Hispanic Black women — have experienced the highest homicide rates, an Associated Press investigation in 2018 found that nobody knows the precise number of cases of missing and murdered Native Americans nationwide because many go unreported, others aren’t well documented, and no government database specifically tracks them.

Over the past year, advocacy groups report that cases of domestic violence against Indigenous women and children and instances of sexual assault increased as nonprofit groups and social workers struggled to meet the added challenges stemming from the coronavirus pandemic.

In response, President Joe Biden promised to bolster resources to address the crisis and better consult with tribes to hold perpetrators accountable and keep communities safe.

The paper also coincides with the landmark appointment of former New Mexico Sen. Deb Halland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo, as the first U.S. Secretary of the Interior of indigenous origins. end .

In her first weeks in the post, Haaland created a Missing & Murdered Unit (MMU) within the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Justice Services to investigate the epidemic of missing women.

Ochs said a truth commission would be able to draw all the various strands together to provide an unblemished portrait of the history of U.S. relations with indigenous peoples.

“It will serve as a vital step towards obtaining healing and justice for centuries of genocide,” she wrote.

Editor’s Note: Last month, scholars and tribal leaders, including Alfred Lopez Urbina, Attorney General of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe; Addie Rolnick, UNLV School of Law; Lauren van Schilfgaarde, Director of the Tribal Legal Development Clinic at the San Manuel Band of Missions, participated in a panel organized by the Center on Media, Crime and Justice on tribal justice issues. Watch the panel on YouTube here.