Russian President Vladimir Putin’s threats of possible use of nuclear weapons against any state that might interfere with Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine have reawakened the world to the dangers of nuclear war. The possibility of military conflict between Russian and NATO forces has significantly increased the risk of nuclear weapons use. Because Russian and U.S.-NATO military strategies reserve the option to use nuclear weapons first against non-nuclear threats, fighting could quickly go nuclear.

Photo Credit: International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear WeaponsPutin’s threats violate foundational understandings designed to reduce the dangers of nuclear deterrence, including the 1973 Agreement on the Prevention of Nuclear War, in which the United States and Russia pledged to “refrain from the threat or use of force against the other party, against the allies of the other party and against other countries, in circumstances which may endanger international peace and security.”

As egregious, worrisome, and risky as Putin’s nuclear antics are, the reaction of the international community until recently has been far too mild. The U.S. response to Putin’s nuclear threats, as well as those of Western governments that also embrace nuclear deterrence ideologies and rely on the credible threat of nuclear use, has been particularly underwhelming.

At the outset of the Russian invasion, U.S. President Joe Biden, answering a question about whether U.S. citizens should be concerned with a nuclear war breaking out, said, “No.” Then, in a May 31 essay in The New York Times, Biden referred to Russia’s “occasional nuclear rhetoric” as “dangerous and extremely irresponsible,” implying that some nuclear threats are more responsible.

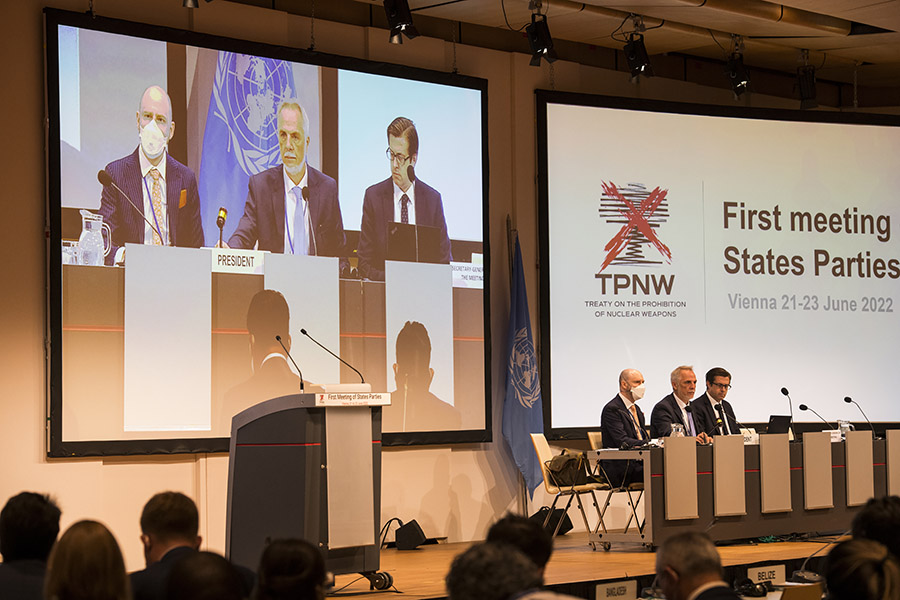

Fortunately, a much needed, more forceful rejection of nuclear weapons and threats of use emerged from the first meeting of states-parties to the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) held in Vienna June 21–23. Citing “increasingly strident nuclear rhetoric,” the TPNW states-parties issued the Vienna Declaration, which condemns all threats to use nuclear weapons as violations of international law, including the UN Charter. The declaration demands “that all nuclear-armed states never use or threaten to use nuclear weapons under any circumstances.”

The TPNW states-parties condemned “unequivocally any and all nuclear threats, whether they be explicit or implicit and irrespective of the circumstances.” Far from preserving peace and security, “nuclear weapons are used to coerce and intimidate; to facilitate aggression and inflame tensions. This highlights the fallacy of nuclear deterrence doctrines, which are based and rely on the threat of the actual use of nuclear weapons and, hence, the risks of the destruction of countless lives, of societies, of nations, and of inflicting global catastrophic consequences,” they added.

The declaration underscores that, for the majority of states, outdated nuclear deterrence policies create unacceptable risks. The only way to eliminate the danger is to reinforce the norms against nuclear use and the threat of use and to accelerate stalled progress toward verifiably eliminating these weapons.

Nevertheless, NATO leaders insist that the alliance must double down on its dangerous nuclear deterrence posture to prevent a Russian attack on NATO member states. In reality, U.S. and NATO nuclear weapons have proven useless in preventing Russia’s brutal war against Ukraine. At the same time, Russia’s brazen nuclear threats have failed to deter NATO efforts to supply Ukraine with weapons needed to repel the Russian onslaught.

Instead, Ukraine’s partners have responded with political, economic, and diplomatic means to help Ukraine defend its territory. The conflict has demonstrated that even for a state or alliance possessing a robust nuclear arsenal, such as NATO, conventional military capabilities are the key to deterring military attacks and to ensuring battlefield success.

The more NATO rhetoric emphasizes the value of nuclear deterrence and of possessing nuclear weapons, the more legitimacy it lends to Putin’s nuclear threats and to the mistaken, dangerous belief that nuclear weapons are necessary for self-defense.

The next global gathering concerning nuclear weapons will take place in August at the 10th review conference of the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). All states must seek to rise above their differences and work together to reverse today’s dangerous nuclear trends.

Non-nuclear-weapon states can build on the TPNW meeting by encouraging wider support for the norms against nuclear weapons. Rather than simply criticize Russian nuclear threats as “irresponsible,” NPT states-parties should condemn unambiguously all threats of nuclear weapons use. They must unite in demanding that the nuclear-weapon states undertake specific actions to fulfill the NPT’s Article VI disarmament provisions. This should include an explicit call for the United States and Russia to begin negotiations on new disarmament arrangements and for all NPT nuclear-armed states to freeze their nuclear stockpiles and engage in disarmament negotiations before the next NPT review conference, in 2025.

Given the growing risk of nuclear war, the first meeting of TPNW states-parties and the NPT review conference must become a turning point away from dangerous nuclear policies and arms racing that threaten global nuclear catastrophe.