Jacques Mosseri, a proud Egyptian and Zionist, would have wanted his collection to be in Israel, but his heirs will decide where it ends up

In 1970, Israel Adler, then the director of Israel’s Jewish National and University Library, visited the Paris home of Rachel Mosseri, a Jewish exile from Nasser’s Egypt. Adler had a big mission, and limited time to carry it out – just 10 days to catalog and photograph the roughly 7,000 documents from the Cairo Genizah that constituted the collection assembled by Mosseri’s late husband, Jacques Mosseri, some six decades earlier.

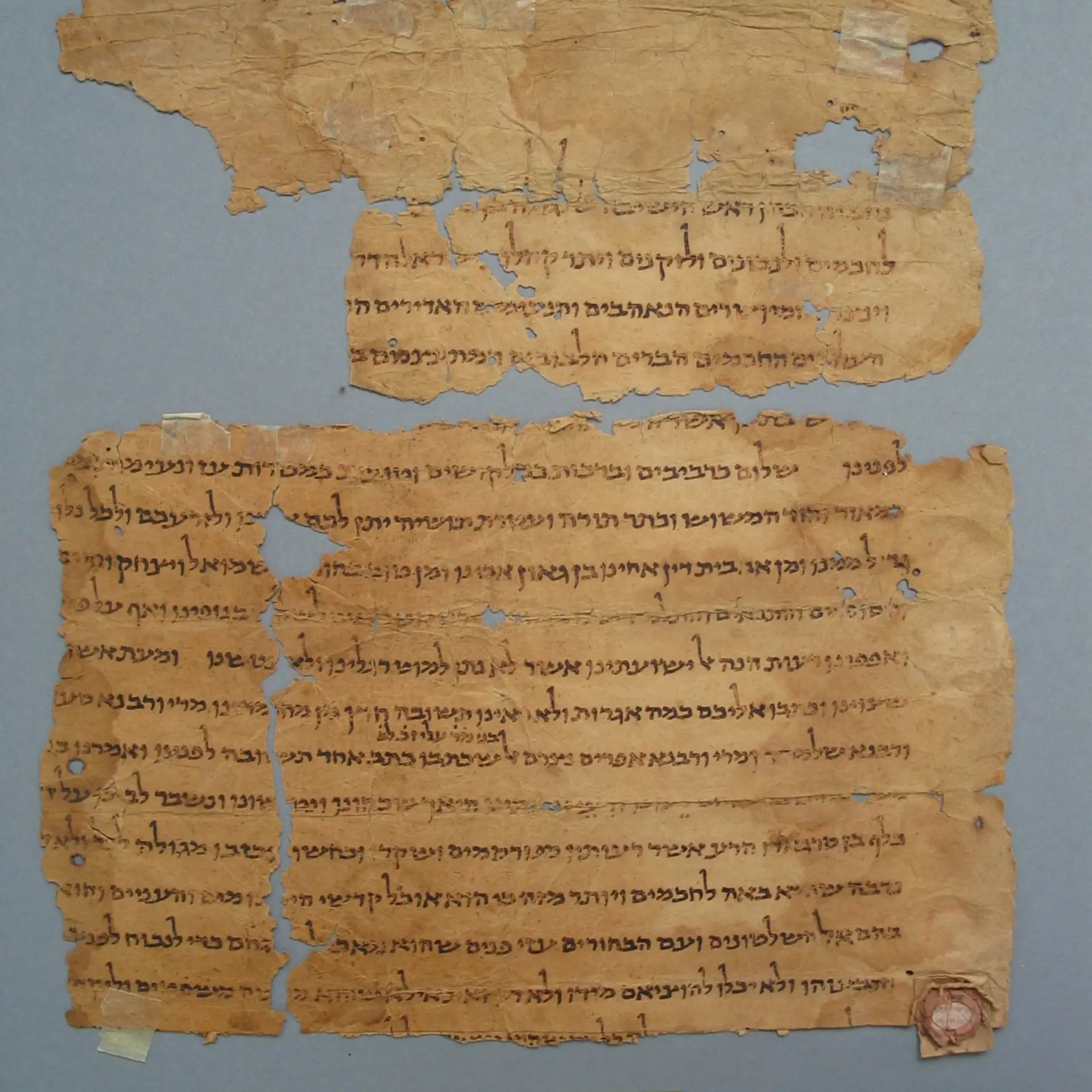

From other caches, most notably that assembled by Solomon Schechter, the world of Jewish scholarship already recognized the long-concealed storage space of Cairo’s Ben Ezra Synagogue as an incomparable source of Jewish books, documents and fragments that dated back at least 1,000 years. Not all of them were sacred texts; some were just “sacred trash,” as Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole titled their superb 2011 book about the genizah: letters, contracts, shipping manifests, even shopping lists that could not be destroyed because they contained the name of God – and they were written in a number of different languages, and not only Hebrew. It was in fact the diversity of the material found in and around the medieval-era synagogue (which in its first incarnation, in the 9th century, was constructed on a site that local Jewish lore said was where Pharaoh’s daughter found Baby Moses) that made it such a valuable source for understanding the lives – and not just the texts – of Jews in the medieval Islamic world. In the case of Jacques Mosseri’s collection, both its whereabouts and an inventory of its precise contents had been lost after his family left their native Egypt for Paris in the 1950s.

Adler’s entrée for access to the Mosseri collection came during a visit by Rachel Mosseri to the National and University Library in 1970. It was there, in Jerusalem, that the scholar, a musicologist by training, learned that the collection was still extant and in Paris – apparently being stored in Mrs. Mosseri’s kitchen – and obtained her agreement for him to microfilm it. (In an article about the collection, former University of Cambridge research associate Rebecca Jefferson writes that a friend of Adler’s told her that the Israeli won over Mrs. Mosseri with a bouquet of violets.)

If you’ve heard of the Cairo Genizah (the Hebrew word, meaning “hiding place,” refers to the spaces traditionally used by Jewish communities around the world to dispose of old books and papers that may have held the ineffable name), it’s likely in connection with the legendary trip of Cambridge University Talmud scholar Solomon Schechter to the Egyptian capital in 1897, when he scooped up roughly half of the 400,000 volumes, documents and fragments that had been stored in and around the synagogue in the Fustat neighborhood and brought them back to England. That was an act of cultural imperialism that many would frown upon today, but it must be said that it was at Cambridge that the artifacts eventually underwent conservation, cataloging and digitization, which is why today they are available for study by scholars and anyone else who has an interest in Jewish history.

Although the Taylor-Schechter collection, as it is called, is by far the largest holding from the Cairo Genizah, it is only one of 84 different such collections, held by both institutions and private individuals worldwide, according to Yitzchack Gila of Israel’s National Library, the successor to Adler’s Jerusalem institution.

Shelomo Dov Goitein, though he died in 1985, remains the historian most associated with the study of the Cairo Genizah, in part because he recognized the capacity of its contents to reveal a complex image of Jewish life in its many aspects in the medieval Mediterranean world and beyond. Aside from the holy books that ended up in the genizah, it also encompassed a vast variety of documents both secular and religious in nature, all of which Goitein employed as a window into the social and cultural history of Jews in the eastern Mediterranean, principally around the turn of the first millennium C.E. Comparing the genizah’s holdings to the collection unearthed in and around Qumran in Israel in the mid-20th century, Goitein once referred to the finds from Cairo as the “Living Sea Scrolls.”

The Mosseri Collection, though far smaller than Schechter’s, is today seen as “holding its own” in quality, according to Marina Rustow, professor of Near Eastern studies and history at Princeton University and director of its Geniza Lab. In fact, she says, it “boggles the mind.” Notes Rustow: “The Mosseri Collection may be small, 6000 pieces – Oxford has double that – but there’s stuff you don’t see in other collections, pieces that caused us to rethink what we knew.”

Asked for some examples, Rustow mentions a letter written in Baghdad prior to 960 C.E. Its author, Nehemia ben Kohen Tzedek, was a breakaway scholar from the Babylonian Talmudic academy at Pumbedita. The letter, a polemic against Nehemia’s predecessor Aaron ibn Sargado, still contains the geonic bulla – clay impression – of Nehemia, making it, says Rustow, the only such seal to have turned up in the genizah.

At the other end of the timeline, Rustow describes a sharia court document dated to 1798 C.E. “It’s not uncommon to find Ottoman-era documents from the genizah,” she says,“but it’s striking that this one was from the same year as Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt.”

It would be another 35 years after Israel Adler’s trip to Rachel Mosseri’s Paris kitchen before the Mosseri family decided to deliver the collection to the same Cambridge University Library where the Taylor-Schechter documents are held. Even then, it wasn’t an outright gift, but rather a 20-year loan, made with the hope that the library, together with the Mosseris, would succeed in raising the money to conserve the items in the collection, many of which were in dire condition, and to store and begin digitizing them. At the end of 20 years, the family was to decide on the permanent disposition of the collection, which Jacques had apparently hoped would end up in Jerusalem. That period will expire in another five years.

If it sounds odd that Mosseri was thinking about the National Library of Israel prior to his death in 1934, 14 years before the state was even founded, itisn’t really. Rebecca Jefferson, who worked on the cataloging of Cambridge’s genizah collections, and who since 2010 has been head of the University of Florida’s Isser and Rae Price Judaica Library, notes that Mosseri“was a strong Zionist, as equally passionate about Zionism as he was about Jewish heritage in Egypt.” From her encounters with members of the Mosseri family, Jefferson says she was left with a “strong feeling” that Jacques and Rachel’s son Claude wants it to end up in Israel, “as long as conditions allow that.”

It’s the “conditions” that make the question of the final home of the Mosseri Collection a tricky one.

The lost catalog

Jacques, or Jack, Mosseri was born in 1884, one of 11 children of Nessim Haim Youssef Mosseri and Elena Cattaoui, scions of two distinguished Jewish banking families in the Egyptian capital. At age 13, Jack was sent to England for a classical secondary education, but as his granddaughter Anne Mosseri-Marlio told the Dubai-produced podcast Kerning Cultures earlier this year, upon his return to Egypt, once his family recognized that “he was not preoccupied with the family business,” he was encouraged to follow his own interests, which included Jewish culture and archaeology as well as philanthropy.

In an interview he gave to the Jewish Chronicle, in London, during a visit there in 1911, Mosseri talked with great pride and extensive detail about the social-welfare and educational institutions that existed in Cairo’s Jewish community. (Unlike Alexandria’s Jews, he said, “We endeavour to deal with our own poor without adopting the convenient but unscientific method of giving them a railway ticket to the next Jewish settlement.”) His obituary in that same paper 23 years later described his efforts as a liaison between the Cairo community and General Allenby’s forces during World War I, and his involvement in Zionist institutions in Palestine (not a given for many Egyptian Jews).

But it is also clear is that Mosseri’s interest in the efforts to build the Jewish homeland were matched with a pride in the rich heritage of Egyptian Jewry, which had a history extending back to the seventh century B.C.E. – if not to the time of Moses, some six centuries earlier – and which was actually growing in the early 20th century, reaching a peak of an estimated 80,000 by 1948. By 1911, Mosseri had begun to feel that the transfer of the contents of the Cairo Genizah out of the country constituted a significant loss to his community, although having been given a proper education in England, he called the loss “somewhat unfortunate,” adding, “We did not at the time appreciate the nature of the hoard with which we so light-heartedly parted.”

In fact, by 1911, Mosseri, convinced that there were still genizah treasures to be unearthed, was exploring both in the vicinity of Fustat’s synagogues and the Bassantine cemetery, where the contents of Ben Ezra genizah had apparently been interred while the synagogue underwent a thorough reconstruction in 1890. Working with an archaeologist, a Semitics scholar and a librarian, Mosseri amassed what was later discovered to be some 7,000 pieces, which were cataloged in 1913 by the librarian, Bernard Chapira – the catalog that was lost after Mosseri’s death.

It was apparently Mosseri’s intention to establish a Jewish museum and library in Cairo, but his untimely death at age 50 prevented the realization of that dream, and the subsequent dramatic decline in the fortunes of Egypt’s Jews made it irrelevant for his heirs, who had left in the decade following the founding of the State of Israel in 1948.

Antisemitism began to rise in Egypt years earlier, in 1930s, in response to clashes in Palestine between the pre-state Jewish community and the land’s indigenous Arabs. During the War of Independence, there were significant attacks on Egyptian Jews, so that even before Gamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the monarchy in 1952 and subsequently became president, nearly half of the country’s Jews had gone into exile. Following the exposure of a series of 1954 terror attacks in Cairo and Alexandria as an Israeli false flag operation intended to destabilize the Nasser regime (in which Israel relied on Jewish Egyptian nationals) and the Suez war two years later, the Egyptian government declared that “all Jews are Zionists and enemies of the state,” and effectively expelled them, forcing them to leave their property behind, and nationalizing their businesses.

Egyptian fascination

Today, there are fewer than 20 Jews left in Egypt, which is fewer than the number of synagogues in Cairo and Alexandria combined. And though there’s not much President Abdel Fattah al-Sissi can do to increase the size of a Jewish population that is dying off, he – and also Hosni Mubarak before him – has been lavish with state assistance for the restoration of those synagogues and other Jewish landmarks.

At the same time, Rustow tells Haaretz, Egyptian scholars have shown definite interest in the country’s Jewish history generally, and in the genizah specifically.

“In 2017,” reports Rustow– winner of a 2015 MacArthur Fellowship and author most recently of the book “The Lost Archive: Traces of a Caliphate in a Medieval Synagogue” – “I was invited by the American University of Cairo to give lectures and seminars on how to use Cairo Genizah documents. And the room was full. There are plenty of scholars interested in the medieval history of Egypt, which is already saying a lot, because it’s not pharaonic, and it’s not 19th century.” According to Rustow, who weighs her words carefully, “attitudes toward Zionism – whether pro or contra – once complicated the study of the Jewish past.” Today, however, she notes, “there are people in Egypt who are fascinated by Jewish history.”

Which raises the question of whether the Egyptians have shown any interest in repatriating the contents of the Cairo Genizah. Dr. Ben Outhwaite, who since 2006 has directed the Genizah Research Unit at Cambridge University Library, says that he’s not aware of the Egyptian government having approached any genizah collection anywhere to propose such a return. In fact, he said, at his library, the closest they ever came to that was a “visit by a deputy of some kind from embassy [in London], who came to see the library on another matter. And while here, someone mentioned the genizah to him, and he said: ‘Oh, I assume of course that you stole it from us.’ But that’s it.”

By all accounts, Jacques Mosseri’s heirs understood that he would have wanted the collection to find a permanent home in Israel. According to Outhwaite, his son “Claude wants to do what his father wanted him to do. If it were Jacques who was now deciding, he’d give the collection to the National Library of Israel in a flash.” But the decision regarding the disposition of the Mosseri Collection will be in the hands of a committee, which will include both family representation and professionals in the field. They need to be convinced that the collection will be safe and secure, wherever it is. And as Anne Mosseri-Marlio told Kerning Cultures producer Nadeen Shaker, it’s her understanding that for the committee to send the collection back to the region, and specifically to Israel, it will need to be convinced that there “will be longstanding peace in the Middle East, including in Israel.”

As the Middle East is a large region, however, and not an especially stable one politically, and Israel itself doesn’t appear to be on the brink of “peace” with its Palestinian neighbors, one could be forgiven for wondering if the arrival of the Messiah might predate the required state of peace.

Haaretz spoke with David Blumberg, the chairman of the NLI, which is currently constructing its new home across from the Knesset building in Jerusalem, a mammoth project that he has overseen since 2007. Blumberg said he has met with members of the Mosseri family as well as their advisors, and that he is “not optimistic.”

“The desire of the father, Jack, was to have it in Jerusalem. But Jack had three sons,” one of whom is deceased. Of the surviving two, according to Blumberg, “One of the sons said it wasn’t safe to bring it to Jerusalem, and that when there is peace with the Palestinians, let’s talk. The second son was more enthusiastic, but he was subject to [outside] influences” who were not enthusiastic about sending the collection to Jerusalem.

Blumberg said he hopes to renew discussions with the Mosseris in person when that again is possible. “We need personal contact with them. I hope that the coronavirus will subside so that we can meet with them again by the end of the year.”

Game changer

The story of the Cairo Genizah is of endless fascination – not only from the historical point of view (and every scrap of paper removed from the Genizah has its own story to tell), but also in terms of the legal, ethical and personal facets related to its removal from Egypt. In the case of the Mosseri Collection, there will also be the next chapter in the story.

On a practical level, however, the actual physical location of this or any other collection declines in significance as the digital technology that allow individual documents to be shared remotely becomes more widespread and sophisticated. Probably the biggest game changer in terms of digitization was the establishment in 1999 of the Friedberg Genizah Project by Canadian businessman Albert D. Friedberg. In addition to running an investment firm and chairing the biotech company Vaccinex, Friedberg also had a doctorate in Jewish studies. With the technical assistance of the late Yaakov Choueka, the FGP has tracked down virtually every artifact from the Cairo Genizah and made it accessible online in color to anyone in the world. The website not only allows viewers to enlarge images, but has a number of other features that greatly simplify genizah research, including artificial intelligence that makes it possible to make “joins” – matches between two fragments from the same document that may have become separated over the centuries, and that today could be on opposite sides of the globe. Digital technology makes it possible to reunite such disparate pieces virtually.

Particularly during a period of international pandemic, when few scholars or anyone else is traveling, it’s of immeasurable value to researchers to be able to continue their work online. And digital technology also allows for examining actual fragments with different frequencies of ultraviolet light, for example. Three-dimensional photography will eventually be another tool that will allow researchers to manipulate manuscripts and documents without needing to handle them in person.

At the same time, everyone in the field agrees, as Rebecca Jefferson tells Haaretz, that although digitization is “90 percent wonderful,” it has its disadvantages. “The manuscripts are unique objects,” says Jefferson, whose book “The Cairo Genizah and the Age of Discovery in Egypt” is scheduled for publication next year, “and there’s nothing like seeing, touching, and even smelling a manuscript.”