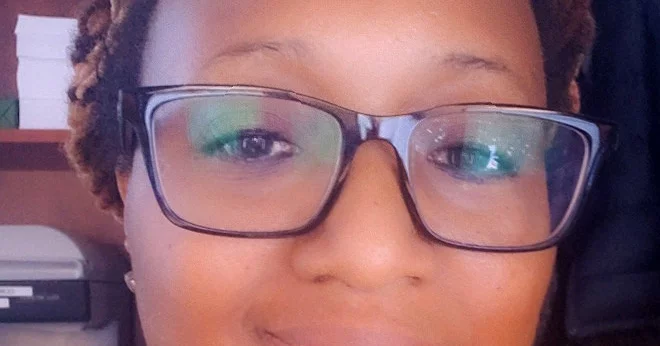

Lakisha Ray benefitted from an advocacy effort that has opened 35 trauma recovery centers across the country

nder attack in her home by an abusive husband, 45-year-old Lakisha Ray says she didn’t realize he’d sliced her chin with a knife. Then she saw “blood, just everywhere.”

“Basically he left me in the house for dead,” she tells PEOPLE of the 2019 assault. She called 911 and was raced by ambulance to the hospital, where she received more than 20 stitches.

Back home the next day, and with her husband on the run, a hospital social worker called to tell her about the Trauma Recovery Center at Cleveland’s Circle Health Services and University Hospitals — a call that Ray says changed her life.

Trauma center staff helped move Ray into a safe house until her attacker was caught. They sent a staff member to the leasing office at Ray’s apartment complex to arrange her move to another facility. They enrolled her in counseling that continued for the next 10 months; they gave her gas cards so she could drive to her sessions, and when Ray’s car broke down, they picked her up to keep her appointments. They sent someone to sit with her in court, where Ray’s husband eventually pleaded guilty and received a 14-year prison sentence for felonious assault.

And they did it all for free.

“They counseled me not just through the trauma, but what led to the trauma. They helped me overcome it,” says Ray. “I honestly cannot tell you where I would be today, mentally or physically, without the Trauma Recovery Center.”

Which is exactly what Robert Rooks envisioned.

Rooks, 45, is co-founder and CEO of the California-based Alliance for Safety and Justice, which after a number of openings this fall and winter has now advocated for local communities to create 35 such trauma centers across the country. Funded with local, state and federal dollars, the centers are a balm to those victimized not only by individuals but also by what Ray describes as ingrained neglect of struggling and violent communities.

“They provide a one-stop shop for people that need help, or need to speak to someone, or need wraparound services as it relates to their trauma or victimization,” Rooks says. “It’s an opportunity to address decades-old trauma for people in communities that may have been forgotten about, or left out of these conversations.”

“We’re moving people from survival mode to living mode; that’s what happens in the trauma center,” he says. “And if people are getting their needs met, their questions answered, then they are less likely to put themselves in high-risk situations.”

A holistic approach

Rooks was an adolescent living in south Dallas as the crack cocaine epidemic ravaged Black neighborhoods, including his own, in the 1980s. His mother moved him out — just 10 miles or so away — but left his father and others among Rook’s friends behind. Several of his friends lost their lives to violence.

At 21 — an age he never thought he’d see — Ray was attending his best friend’s funeral, he says, “when I made a commitment to do something different, to make sure the next generation does not have to experience what me and my friends were experiencing.”

He became a community organizer and activist focused on criminal justice, victim advocacy and sentencing reform. He signed on as criminal justice director for the NAACP. The interactions that informed his work included one in the late 1990s with a young mother in a low-income neighborhood of Hartford, Connecticut, who told her she wouldn’t let her babies play outside for fear of gunshots.

“I wondered, when will this fear be important enough for the government to take action?,” he wrote in an essay after the killing last May of a Black man, George Floyd, by a white Minneapolis police officer.

The government response he’d previously seen was wrongheaded, he says.

“People struggling with addiction? Send in police,” he wrote. “People in need of mental health help, send in police. People struggling economically and with homelessness? Send in police.”

He added: “Police and incarceration were the primary response to nearly every social problem in Black communities in the 80’s, 90’s, 2000’s. These ‘tough on crime’ strategies tore families apart, depleted community resources and led states to build more and more prisons. Sending in police in response to problems turns the community in need of help, of everyday people that just want safety and health, into a community of suspects.”

Trauma recovery centers aspire to a different approach, he says.

The model, launched in 2001 in San Francisco, with a holistic healing center run by the city’s health department, was inspired by research showing that victims often take longer to recover psychologically than physically. The reform advocacy group Californians for Safety and Justice, working with the University of California San Francisco, took the concept statewide in 2013. Rooks’ group spun off from the California effort.

In Peoria, Illinois, where the Wraparound Center that embraced the model advocated by Rooks’ group opened in a middle school in 2019, Tina Rucker found its services invaluable as she recovered from the shooting murder of her nephew, 38-year-old Marshawn Tolliver.

A community college student who’d just earned A’s in his welding course, Tolliver was outside Rucker’s home, where she was on the front porch, in August 2019. She stepped inside just as a man emerged from an alley. “I heard a pop, and my nephew yelled my name,” she says. “I heard four more shots.”

“He was begging me not to leave him, so I just stood there,” Rucker says.

Tolliver died 13 days later. He’d been buried for a week when a friend and community activist working with the new center told Rucker about its upcoming opening, and she went.

“I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t stay in that house knowing my nephew got murdered there,” she says. At the center, she heard, “What if I tell you that we can help you? We can move you and we can make you feel safe and home again.”

“They became like a family to me,” Rucker says. “I went to counseling like two days a week. And then I upped it to three. I used to say I didn’t need it, but yes I did need it. And I needed it tremendously.”

“I’m 55 years old, and I’ve never been through something like this,” she says. “But that Wraparound Center, they are a help.”

‘A public safety system that values everyone’

Rooks says the model is not imposed on a community, but rather the community is urged to create a center around its own needs. “In some cases you’ll see where a trauma center is at a hospital, and another where a trauma center is situated in a homeless center, or a women’s center.”

Staffers include social workers, counselors and therapists drawn from the communities themselves. Financial support also is primarily local, tapping into city, county or state budgets — often through the federal Victim of Crime Act — as well as the budgets of prosecutors who are taking note of the centers’ successes, he says.

Indeed, 69 percent of those who seek help at a trauma recovery center are more likely to work with police to help solve their cases, according to the Alliance for Safety and Justice — reflecting a significant shift among some individuals in how they perceive law enforcement.

Rooks hopes his alliance can work to double the number of centers in the next three to five years, building on their past work advocating in states such as California, Florida and Texas that have the largest jailed populations.

Just consider, Rooks says, how much the unaddressed traumas of addiction and mental health struggles contribute to those numbers, and how they might be reduced with more help.

“To the extent that we can get states to open up their pocketbooks, or counties and cities to open up their pocketbooks and provide support for these trauma centers, I think it will be hugely helpful,” he says. “Hugely helpful.”

“People might think that victims want to lock people up and throw away the key,” Rooks says. “Our experience is that victims want to get at the root causes of crime. They want crime to stop. They’re not wedded to locking someone up.”

“What we’re trying to do,” he says, “is create a public safety system that values everyone.”