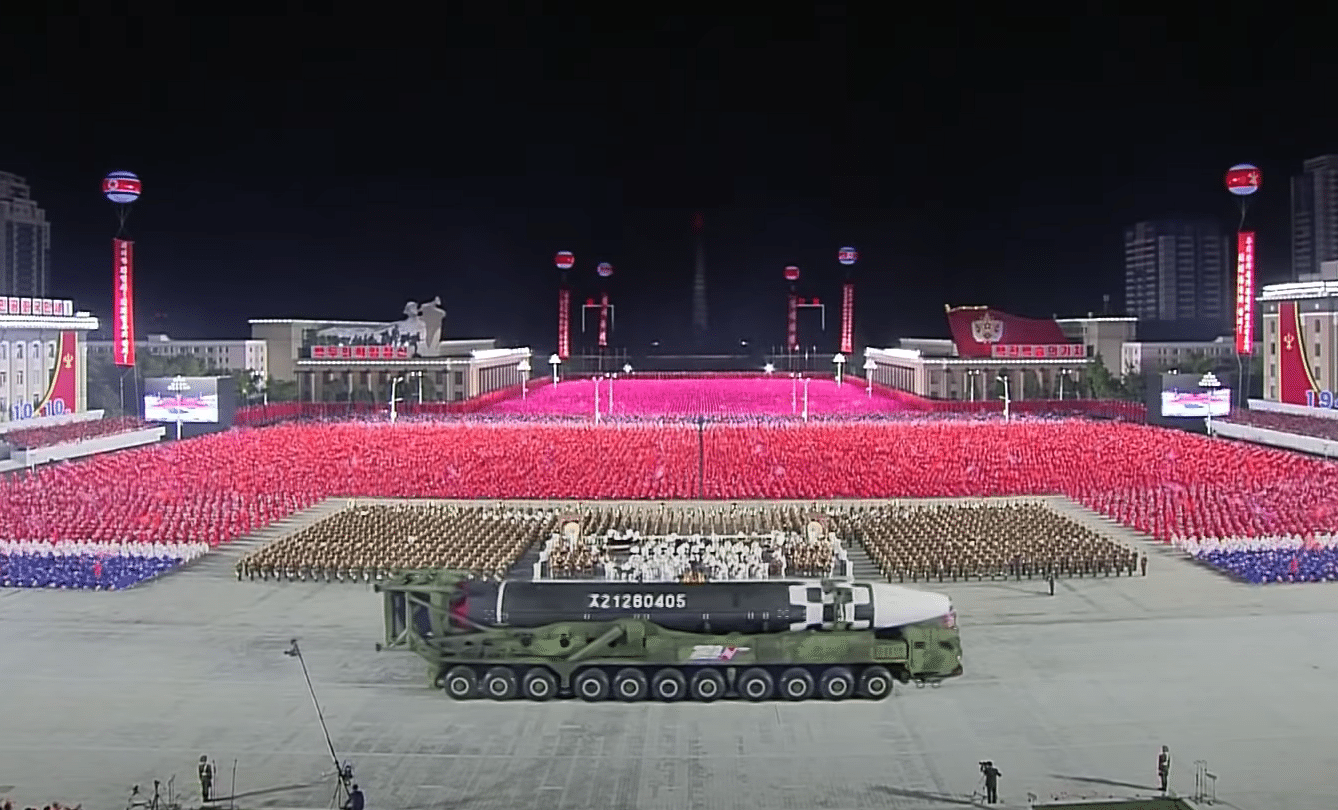

Everyone loves a good parade, North Korea included. And the military parade in Pyongyang on October 10 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the founding of the Workers’ Party of Korea did not disappoint. It included intricate troop formations, an array of military equipment, lights, cameras, drones, and even fireworks. And the middle-of-the-night setting created the perfect dramatic backdrop for Kim Jong Un to show off shiny new things as symbols of the country’s strength and perseverance despite the hardships of 2020.

And show off he did, making good on his earlier promise to reveal a “new strategic weapon.” The stars of the parade were a new larger intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and a new submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). While the reveal may not have happened as “soon” as his original statement last December might have suggested, it certainly was done with flair and stole international headlines, as the world scrambled to assess what to make of these two new missiles.

While the new ICBM is touted as the “largest” road-mobile, liquid-fueled ICBM in the world, that feat is actually not much to brag about. As Vann Van Diepen and Michael Elleman point out in an article published on 38 North, most countries that have ICBMs work to create smaller, solid-fueled systems to make them more mobile, more concealable, and faster to deploy. A liquid-fueled missile of this size makes little strategic sense given the difficulties it would have traversing most of North Korea’s bumpy roads, and because it would likely need to be fueled only after it was erected at a launch site, making it vulnerable to preemptive attacks.

So the potential advantages that such a large missile may have—being able to carry heavier payloads or potentially multiple reentry vehicles down the road—come at a great cost. And the new Pukguksong-4 SLBM, given the limited information about its dimensions and potential range, seems to provide only marginal improvements over the Pukguksong-3 SLBM North Korea tested last year.

But the fixation on the two new ballistic missiles has obscured a far more important story about North Korea’s overall military modernization. While the new ballistic missiles themselves may ultimately bring little in the way of strategic benefits, the level and pace of North Korea’s broader military modernization should compel US policy makers to rethink the current approach to denuclearization.

In an article for NK News, Joost Oliemans and Stijn Mitzer broke down a long list of what else was new during last Saturday’s parade that didn’t make headlines, from camouflage patterns, uniforms, and accessories, to small arms and artillery systems, to main battle tanks and short-range air defense systems, to new aircraft. Importantly, the list also includes new and varied types of transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) for missiles, suggesting that North Korea has overcome earlier shortages and has found a way to make its mobile missile force more robust. Notably missing from the parade lineup was North Korea’s old Scuds and Nodongs, which seemingly have been replaced with newer systems.

Kim Jong Un even drew special attention to the new look of North Korea’s military, noting that compared to even five years ago, “the modernity of our military forces has remarkably improved, and anyone can easily guess the speed of its development.… Our military capability has developed and changed to such an extent that no one can make little of and keep parallel with it.” Although perhaps a bit overstated, these changes do indeed require serious assessment, especially by South Korean and allied forces.

Despite Kim’s emphasis on the defensive nature of North Korea’s military, the parade put a fine point on where North Korea relations stand today with respect to the United States and South Korea. They are a far cry from the optimism and goodwill that existed in 2018 at the beginning of the summit-driven diplomatic process. Even the friendly shoutout to South Korea in the middle of Kim’s speech, expressing hopes for the day to come “when the north and south can take each other’s hand again,” was rather offset by the new short range and combat equipment that improves the North’s capabilities against the South.

Moreover, while Kim’s messaging was largely aimed at a domestic audience—creating the optics that the party is strong, the military is stronger, and the nation will overcome the hardships of 2020—the external message was clear: North Korea is not waiting to see if its relations with the United States will improve, but will continue to advance its military development until it does, regardless of how difficult that may be.

After the dust settles following the US presidential election and a winner is announced, the issue of North Korea’s evolving nuclear threat will remain. A second Trump administration or a new Biden administration will be dealing with a North Korea that has expressed a waning belief that the bilateral relationship will actually change, making the return to negotiations a hard sell.

While both the Trump and Biden camps have expressed a desire to get back to “serious” diplomacy, Saturday’s military parade was a vivid depiction of how the whole US approach—whether summit-driven or working-level talks—is outdated. Long, difficult negotiations for a grand, comprehensive deal may have been the right approach when dealing with a country with a burgeoning nuclear capability. But the level and pace of North Korea’s conventional and strategic weapons development and the deep mistrust on both sides calls for a more agile and incremental approach to curb development now, while still working toward more ambitious long-term goals.

The framework for the range of issues that need to be addressed already exists in the Singapore Joint Statement. Working within that framework, a series of small agreements negotiated step-by-step would create small, early, and potentially frequent wins for both sides and help build trust and momentum for further negotiations. While this might not be politically palatable in Washington, if both sides start to see modest payoffs and gain confidence that this is more than a publicity stunt, more can be on the table in the future. Such an approach also has the advantage of halting North Korea’s advancement now, preventing its further refinement of weapons under development.

This does not mean “giving up” on denuclearization. It means differentiating a denuclearization process from what the United States has done in the past to try to prevent countries from going down the nuclear path in the first place. The tools and steps needed to slow or stop a moving train are not the same as those needed to keep the train parked at the station. As such, the United States needs a new approach that works to curb North Korea’s advancement and buildup of its nuclear capabilities in the short term, but simultaneously works to build the kind of relationship it would take to eventually get Pyongyang to the end of the nuclear disarmament road.

The rate of change North Korea has demonstrated in its military modernization and strategic weapons development over the past five years is telling. Despite “biting” sanctions, Pyongyang has consistently shown a superior ability to adapt to the times and find ways to meet its strategic goals. The question is whether US policy makers can be equally as adept at adjusting their approach to one that will bring about incremental results to prevent a repeat modernization story five years from now.