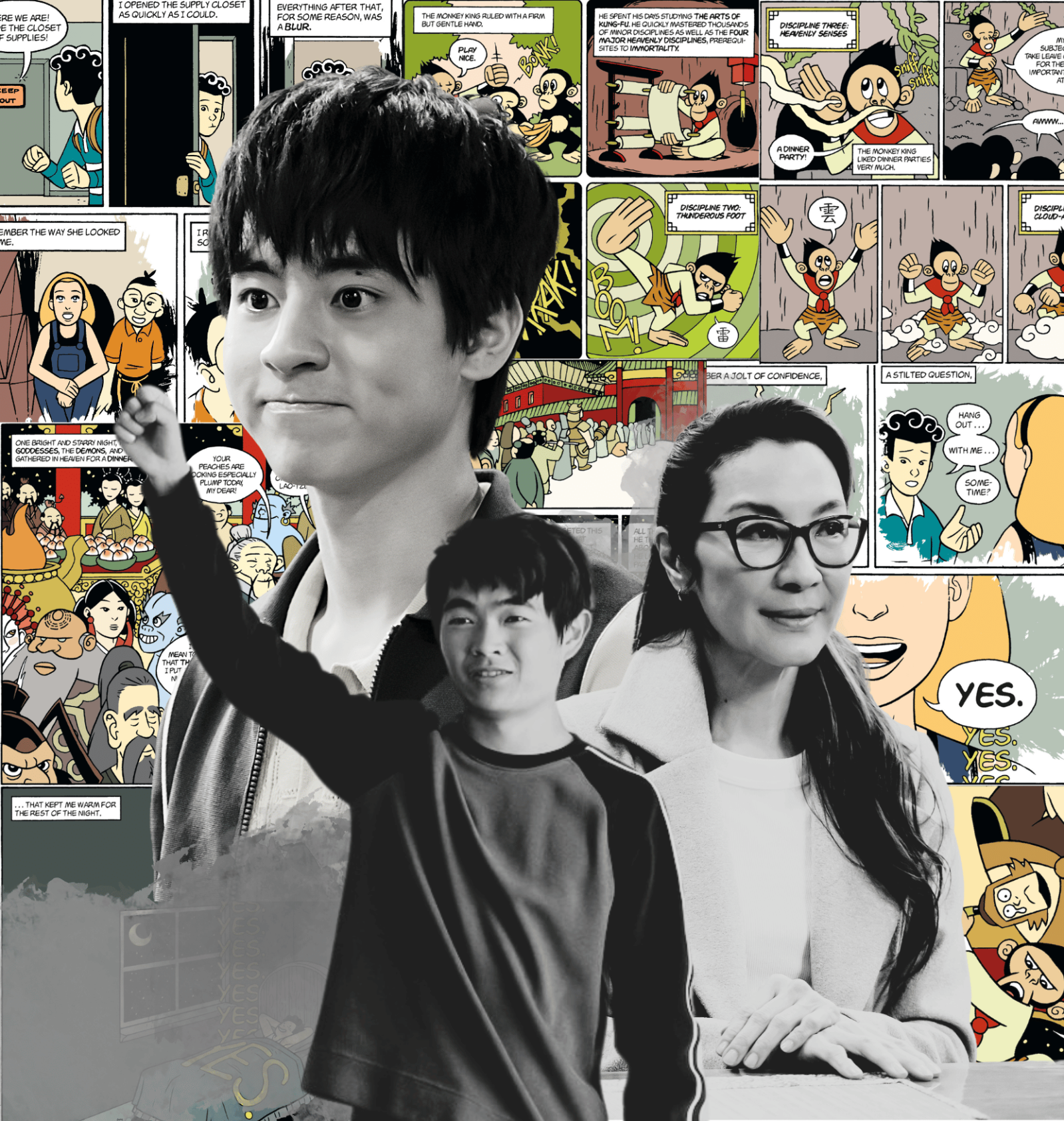

After years of printing comics at Kinko’s and selling them at conventions and local shops, Gene Luen Yang didn’t expect his 2006 graphic novel American Born Chinese to get the attention it did. Blending the coming-of-age journey of Jin Wang, the son of Chinese American immigrants, with the adventures of characters from the Chinese epic Journey to the West, the best-selling book was a National Book Award finalist and won the American Library Association’s Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature. Yet despite its success, a screen adaptation wasn’t a goal for the author.

“I don’t think there was a lot of interest in shows with Asian American protagonists back then,” Yang tells me. The Margaret Cho–led All-American Girlhad been canceled in 1995 after one season, and networks had hardly rushed to pursue other shows centering the experiences of Asian Americans. Plus, he had his own doubts: he thought it would be hard to effectively adapt and translate the edgiest of the book’s three storylines—in which he has a character called “Chin-Kee” embody various racist anti-Asian stereotypes in an attempt to illustrate how harmful they are—for a TV audience. Then, a few years ago, he met Melvin Mar, a producer whose credits include the ABC sitcom Fresh Off the Boat, who in turn introduced him to Kelvin Yu, a producer and writer (Bob’s Burgers) who also appeared on Aziz Ansari’s Netflix series Master of None.Yang says Yu understood the challenges of bringing the graphic novel to life onscreen, and also had ideas about how to expand the story and the cast, address the difficult plotline, and make sure the show could resonate with a new generation.

Mar, Yu, and Yang are now among the executive producers on American Born Chinese, a new family-friendly series that premieres May 24 on Disney+ and is directed by Lucy Liu and Destin Daniel Cretton (Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings). Yu, the showrunner, explains that both the television-production landscape and viewers’ expectations have shifted over the years. “When I was growing up, it was a few networks trying to appeal to tens of millions of viewers, but that’s not where we are now,” he says. “Look at what’s popular on streaming—it tends to be things that aren’t straight down the middle. People are more willing and able to dive in.”

American Born Chinese features what Yu refers to as “an embarrassment of riches of Asian and Asian American talent.” Ben Wang, whom Yu jokingly calls “the Asian American Michael J. Fox” because “you can’t help but root for him,” stars as teenage everyman and emerging hero Jin Wang. Daniel Wu and Jim Liu portray Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, and his son, Wei-Chen, while Yeo Yann Yann and Chin Han give two of the show’s most emotionally resonant performances as Jin’s parents Christine and Simon Wang. And there’s a mini-reunion of cast members from Best Picture winner Everything Everywhere All at Once, as Academy Award winners Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan and Academy Award nominee Stephanie Hsu lend additional star power. Once “the only Asian face” on sets, Quan tells me it was a joy to collaborate with so many fellow Asians and Asian Americans: “It warmed my heart to see how far we’ve come.”

While the book’s three distinct storylines—all focused on individuals grappling with questions of identity and belonging—come together toward the end, the new series allows its many arcs and characters (human and divine) to interact from the beginning. It also brings the story from the ’90s into the present and spends more time at home with the Wang family than the book, in which Jin’s parents are minor characters. When you turn a self-contained 240-page graphic novel into an eight-episode series, you’re going to have to add some material. But far from feeling extraneous, the family scenes are among the funniest and most moving in the show: Christine taking Jin shopping and striking out with every suggestion; Simon realizing that he has let his wife down by giving up on some of their shared dreams; Jin unhappily listening to his parents argue in a language he struggles with from the other side of the wall. Many of the challenges Jin faces, his questions about who he is and where he belongs, are mirrored in his immigrant parents’ lives.

Chin Han points out that in their scenes together, he and Yeo Yann Yann performed “over 90%” of their dialogue in Mandarin, with subtitles: “And the writers trusted it would land, and trusted the audience to follow the story and the emotional beats.” Both said they appreciated the show’s portrayal of an Asian American family. “An Asian family is often seen in a particular way, focused on achievement, but my experience of being within an Asian family is much more interesting and varied,” says Chin Han. Yeo Yann Yann loved that her character was “trying so hard to understand her son. She’s not the typical Tiger Mom we see on some shows.”

In the series, there is no cousin “Chin-Kee”; instead, we meet Freddy Wong, a character, played by Quan, on a ’90s show within the show. Jin is humiliated when a classmate compares him to the accident-prone Wong, the butt of every joke on the old sitcom. Quan initially turned down the role because he feared it was “exactly the kind of portrayal of Asian characters that we don’t want to see in 2023,” but changed his mind when he learned more about the character’s journey.

“We actually get to meet the actor who played the character later on,” Quan says, referring to an episode in which viewers learn what it felt like to always be the punch line, not the hero. “It was us bringing a mirror, showing the audience what it was like being an Asian actor in the ’80s and ’90s. Those were the kind of roles I was auditioning for, left and right. They were trying to show how representation like this trickles down and affects a regular kid like Jin—what it does to his self-esteem, his sense of identity.”

Full of stunts and jokes and mythological figures, anchored by a realistic and heartfelt family story, American Born Chinese plunges readers into worlds both like and unlike our own and resists easy categorization. It also doesn’t seem to have to grapple with the question of whether a sizable American audience will watch or understand a show about an Asian American family—perhaps because that question has been answered by shows like Fresh Off the Boat, which ran for six seasons. “Some previous shows about Asian Americans—and there aren’t many, right?—were sort of forced to deal with certain aspects of the experience because nobody had ever done it before,” Wang says. “Ours is one of the first shows about an Asian American experience that feels like it can just have fun.”

American Born Chinese is nothing like Everything Everywhere All at Once, yet the projects share more than cast members—a sense of playfulness and creative freedom permeates both. Yu says one of the lessons he took from working on Master of None is that an audience will respond when creators are “laser-specific” about an experience. American Born Chinese is a product of many individuals’ experiences—Yu based Jin’s parents on his own and the character of Freddy Wong on one of his first acting roles; the set designers took inspiration from their families’ homes for the Wangs’ house. “If you make something true, something you like, something that makes you laugh—if you do all that, and other people don’t like it, you can sleep at night,” Yu says. “What you couldn’t live with is if you pandered to what you thought an audience wanted.”

I was in my 20s when I first encountered American Born Chinese. It was only the third or fourth graphic novel I’d read at the time, and I remember being first charmed and then drawn into the imaginative world of the book, though I was outside its target age range and my upbringing as a Korean American adoptee bore little resemblance to Jin’s. Asian American characters were scarce in the books I’d read growing up—when I did find us, we were often stereotypes or sidekicks—but I’d always wanted to believe that there was an audience for stories focused on our lives, our families, our histories. I wanted to help write those stories, and I also wanted to read more and more of them. I still do. If it is slightly easier to find them now, it is in part because readers—and viewers—continue to demand more.

“It’s a privilege to get to elevate so many talented people. It’s a time for us to flex,” Yu tells me. “The door has cracked open, and the responsibility is now ours—what are we going to do with it?”

Yang is gratified to know the comics he once drew and stapled by hand have become a foundation on which others can build their own Asian American stories. Now that his book is a show, the collective work of so many, his creation is “no longer a ‘me’ story,” he says, but “an ‘us’ story.” He hopes viewers will reflect on “whatever part of their lives makes them feel like an outsider, [and] learn to see that as a gift.” It’s a point echoed by Quan: “We all work so hard to find ourselves, our identity, and sometimes we want to be like others. But there’s beauty in being who we are. We all need to give ourselves a little more love.”