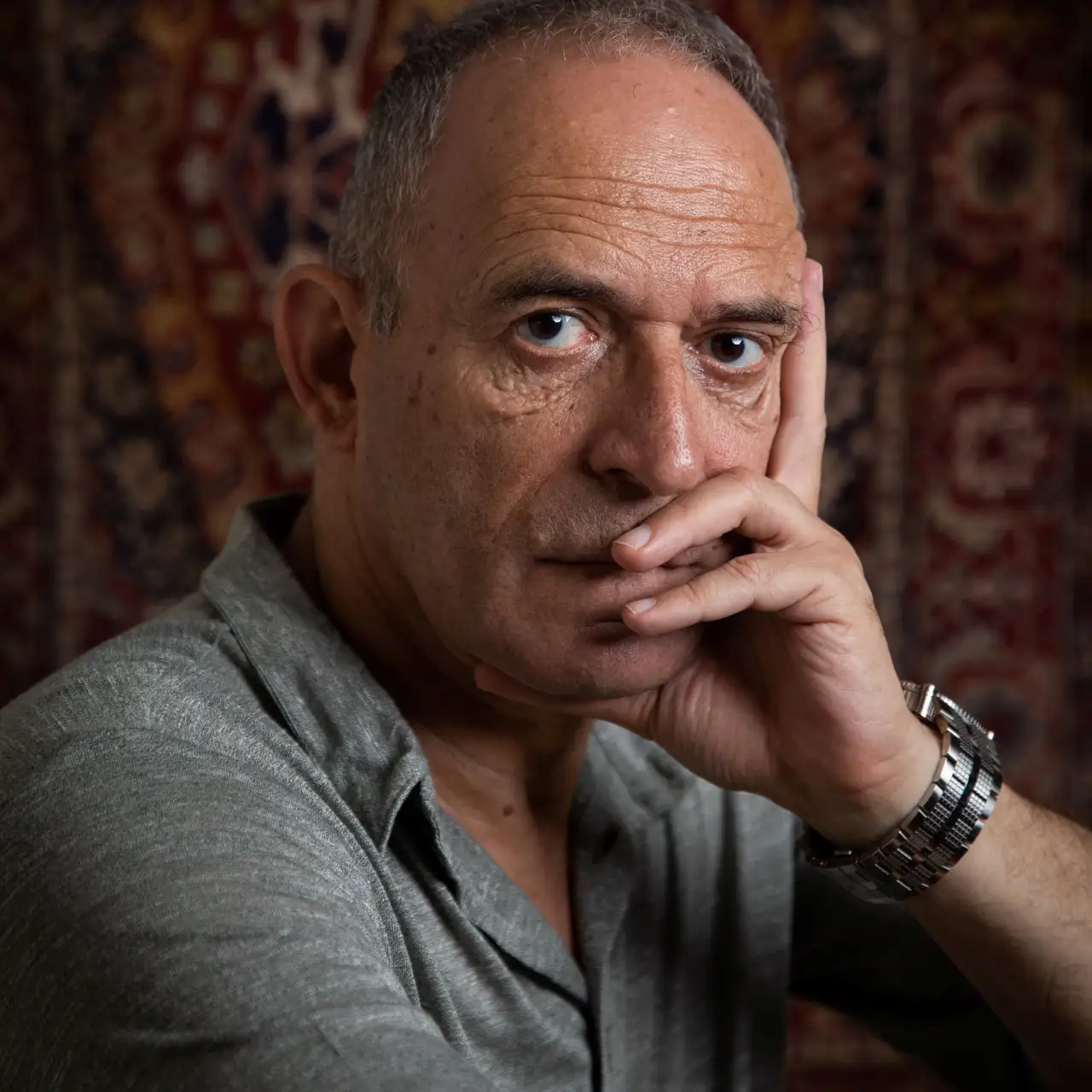

Suddenly in midlife Israeli poet Tamir Greenberg found himself taking care of three young Palestinian men. He wrote a disturbing book about one of them, who died of an overdose

On a rainy winter day in central Tel Aviv, as Tamir Greenberg was strolling down Allenby Street, a barefoot young man garbed in shorts asked him to buy him something to eat.

“He didn’t ask for money. He just wanted me to buy him food, and that really grabbed me,” says Greenberg, a poet, playwright and architect, who is now the CEO of the Shenkar College of Engineering, Design and Art. “I bought food for him of course and asked how he had ended up in the street. I was completely unaware of how that happens. He said he was from East Jerusalem, that his name is Alaa a-Din Shweike, and he told me his life story. It amazed me.”

Greenberg asked to meet with Shweike, then 20, the next day at the Tel Aviv municipal welfare department. “I was sure he wouldn’t show up, but he did. We met with Yoav Ben Artzi, head of the municipality’s department for homeless people. There, he related that he’s a drug addict, so is his father, and his mother isn’t in the picture. I was in shock.”

Ben Artzi suggested a referral to a free rehab program. “He asked, ‘And who will drive me there?’ I said I would,” says Greenberg. “Alaa said ‘But I don’t have any clothes.’ I said – ‘Okay, I’ll buy some for you.’ Ben Artzi said, ‘You’ll also have to be in contact when he’s in rehab.’ I said all right, I’ll stay in touch,’” smiles Greenberg.

Most people would have ignored him, I suggest. “I know that it’s not to be taken for granted,” says Greenberg, downplaying the heroic dimension of his action. “At first I thought the episode would be short. I figured that I would be helping someone in great distress like any decent person would. When you see someone trampled by life, you don’t just walk on, you help. I thought there would be very clear boundaries to what I was doing. But as time passed – I discovered that addicts are the world champions in breaking boundaries.”

When Shweike was in rehab, his two younger brothers Diaa and Baha ran away from boarding school and knocked on Greenberg’s door. He told them he had no intention of putting them up in his home and brought them back to the school. Meanwhile Alaa successfully completed his rehab and Greenberg helped him to rent an apartment in Jaffa with his girlfriend, and helped his two younger brothers move there too.

But soon the brothers told Greenberg that Alaa was using drugs again. Greenberg found himself drawn in and taking responsibility for the three Palestinian brothers. “Every time a problem arose, I was the address. If he had a problem with drug dealers – they turned to me. The same applied regarding the police, detentions, prison.”

When Shweike was in rehab, his two younger brothers Diaa and Baha ran away from boarding school and knocked on Greenberg’s door. He told them he had no intention of putting them up in his home and brought them back to the school. Meanwhile Alaa successfully completed his rehab and Greenberg helped him to rent an apartment in Jaffa with his girlfriend, and helped his two younger brothers move there too.

But soon the brothers told Greenberg that Alaa was using drugs again. Greenberg found himself drawn in and taking responsibility for the three Palestinian brothers. “Every time a problem arose, I was the address. If he had a problem with drug dealers – they turned to me. The same applied regarding the police, detentions, prison.”

Alaa was in and out of rehab centers with Greenberg by his side, helping as much as he could, for 15 years. “In the rehab center, when I came to visit him, I saw the universe in all its beauty,” says Greenberg. “There I saw divine grace. Those are the places where lovingkindness prevails.”

There was an unwritten agreement between Greenberg and Alaa that when he was actively addicted Greenberg wouldn’t let him sleep in his home. “I explained to him that if he uses drugs he can’t come to me,” says Greenberg. “There was something noble about him. He would say: ‘Just take care of my brothers.’”

In 2014 Alaa came to him high on drugs and Greenberg refused to let him into the house but scheduled to drive him to rehab. Alaa meanwhile went to visit his father in East Jerusalem and died there of an overdose.

“I’m still trying to grasp his death,” Greenberg admits. “I have guilt feelings for closing the door on him. I know that I did the right thing, but that didn’t stop me from feeling guilty.”

Human beings in the street

The two brothers, Diaa and Baha, now 34 and 32 respectively, are married with children, and consider Greenberg a father for all intents and purposes. Their pictures adorn his living room and he proudly displays the photos of his Palestinian grandchildren, who call him grandpa. Recently he even helped them to open a restaurant-bar in Haifa’s lower city, Bibo Bar. “I never thought that I would take three Palestinian teenagers under my wing,” explains Greenberg. “I saw them as human beings who had ended up on the street and were in serious trouble.”

In the book “Heroin, the Immortality of the Soul” you see the name of an Arab and think that it’s political, but good God, we’re talking about human beings. The fact that he’s an Arab isn’t the issue. That was never the issue for me. Every ideology ends badly.”

His book of poems “B’Hesed” (With Lovingkindness), which was published by Erez Schweitzer through Hakibbutz Hameuhad has just been released. It compiles three separate poetry books Greenberg, 62, published: “Self Portrait with Quant and a Dead Cat (Am Oved, 1993) “Thirsty Soul” (Am Oved, 2000) and “Heroin, the Immortality of the Soul” (Hakibbutz Hameuhad, 2017).

The new release also contains an essay about Greenberg’s poetry written by Prof. Dan Miron. “This word, ‘b’hesed,’ which was chosen as the book’s title profoundly says what I wanted to express: That in spite of the pain there is lovingkindness in the world. Really, there’s terrible pain in this book, but there is also lovingkindness in this world,” Greenberg says.

Miron’s efforts to do justice to Greenberg’s poetry show in the rear book jacket. “When his first collection of poetry was published, it seemed that Tamir Greenberg was destined to be one of the leading Hebrew poets of his generation,” Miron wrote. “His next two books kept the promise and together presented a sophisticated, precise and beautiful body of work, exceptional in its character and its quality.”

Greenberg, who received the Prime Minister’s Prize for Hebrew Literary Works in 2000 and 2009, has been lauded by critics for years. Upon publishing “B’Hesed,” poet Bacol Serlui wrote, “Tamir Greenberg is one of the great, sophisticated poets living today, with a marvelous command of the work of poetry.” Ruth Almog wrote about his book “Heroin, the Immortality of the Soul”: Today, there are very few great poets. I know two or three of them, and one of them is Tamir Greenberg.”

Smoke inhalation

Greenberg was born in Netanya to parents who immigrated from Romania. His mother, who died recently at the age of 89, was a housewife, and his father never held a steady job. “At one time he was a handyman, and later he was an antiques dealer and hung around the flea market in Jaffa. He was a very bad salesman,” says Greenberg. “We were very poor. When I was young we lived in a 20-square meter hut. There was no electricity and the bathroom was a pit in the yard, which as a child I was afraid to use. When I was 9 we moved to a more spacious apartment in Netanya. I remember that I felt that I was in a palace. I kept turning the switch on and off.”

Greenberg has an older brother who is now a rabbi in New Jersey, and three sisters. In the poem, “There, in an attractive cemetery” one can find allusions to the family’s tragedy when his younger brother, Eliezer, died of pneumonia. “There, in an attractive cemetery in the south of the city, the cold body of the child was placed. Nobody delivered a eulogy. Kaddish was not said. Two to three pats of a shovel and a tiny wooden plank was placed as a tombstone.”

At the age of 14 Greenberg was sent to the Steinberg Boarding School in Kfar Saba. “My home wasn’t doing well and it was a boarding school for gifted children. So it provided a very good solution. Those were marvelous years for me. In that place I was shaped as a poet. I had wonderful teachers of literature. One of them was Mina Steinitz, the mother of Knesset member Steinitz. I started to devour modern and classical poetry.”

In the army he served as a paramedic. “One day when we were in the Golan Heights a shy, goodhearted, smart and introverted guy named David Bitan joined the team of paramedics,” he says, with a broad smile. “On a very cold Friday afternoon I fell asleep in a room with a gas heater. The flue was clogged and soon the room was filled with smoke. Bitan, who was on duty in the clinic, ran to the smoke-filled room and found me unconscious. He rescued me, administered artificial respiration and called for help. I was sent to a hospital. When he came to visit, I was happy and I thanked him, and he smiled dismissively and said, ‘Forget it, I brought you a candy bar.’”

Bitan was indicted this month for taking bribes, fraud and money laundering in seven cases. Greenberg sighs and says: “I remember his goodness. He saved my life.”

During his military service, his father died at the age of 51 from a stroke. “I don’t recall that my father took any interest in my welfare or my needs. He was a unique person who was fluent in many languages, he was a kind of Rami Saari (a poet who translates poetry and prose from esoteric languages), but not a person who used his talent. He wasn’t an easy person, very self-centered, childish. As children we were afraid of his anger. He wasn’t physically violent but he created a bad mood in the house the moment he walked in.”

Censored in Acre

Greenberg published poetry for the first time after his army service. His venues were the literary section of Maariv, edited by the poet Moshe Ben-Shaul, and the periodical Achshav, edited by Gabriel Moked. “I wrote poetry from an early age,” he says. “But I didn’t think I’d be a poet. I only dared to call myself a ‘poet’ after that book was published. After my discharge I thought I’d be an artist. I spent a lot of time in galleries,” he smiles, pointing to his paintings that hang in his apartment in Tel Aviv.

Although he was accepted to the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem, he decided to forgo becoming an artist. “I ran into a Bezalel student and asked what it’s like to study here. He said it’s very expensive and the materials cost a lot. I got scared. My financial situation was terrible. I supported myself from an early age and after my father’s death I helped my mother. I decided to give up on studying art.”

Because he was preoccupied with making a living, he postponed academic studies, and only at age 26 began studying architecture and city planning at the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa. He didn’t neglect his writing. He wrote his first play, “Mizmor Le’David” (Hymn to David), which described the lives of gay men in Israel after the discovery of AIDS, as a student, and staged it at the Acre Fringe Theater Festival in 1986, starring Moshe Ivgy. The drama caused by the play outside the theater, when one of the monologues was rejected by the censors, is documented. “With hindsight I think that they were right in artistic terms,” he says forgivingly. “I wrote my life there,” is how he sums up his attitude to that play.

At age 34, a year after finishing his studies, his first book of poetry, “Self Portrait with Quant and a Dead Cat” was published, for which he received the Luria Prize for poetry.

“Greenberg deals obsessively with death,” writes Ketzia Alon in Hamusach, a literary supplement. “This preoccupation is evident in the name of his first book of poems, and the lyrical treatment of death is the underpinning of the entire book – the first poem, which opens the book, is called ‘Elegy,’ and the five following poems come under the fraught title ‘Mourning,’ and are numbered in sequential order.”

In 2008 the play “Hebron,” written by Greenberg and directed by Oded Kotler, was staged, and sparked an uproar. There were protests and a Knesset debate on it. “The reactions amazed me,” says Greenberg. “In terms of public relations it helped the play, but as a playwright it was very sad for me to be so radically misunderstood. My play was not anti-settler. Rabbi Menachem Froman came to see it and came to talk with me afterwards. He introduced himself and embraced me. Nobody understood the play the way he did. It’s a religious play, which deals with belief in God.” The play was also staged in London and Frankfurt and appeared as a book in the United States and France.

Greenberg rejects any political interpretation of his work. “Israel Hameiri wrote in an article entitled ‘The Drama of the Mythical Other’ that in ‘Hebron’ there is no ‘other.’ The Arab is not ‘the other’ and the Jew is not ‘the other.’ They are people in themselves,” he quotes and adds: “I think that ‘Hebron’ deals with a fraught political situation but that’s the starting point. In my third book, ‘Heroin, the Immortality of the Soul,’ you see an Arab and think that it’s political, but good God – we’re talking about human beings, the fact that he’s an Arab or a Palestinian isn’t the issue. It was never the issue as far as I’m concerned. There’s no ideology here, it’s the most natural thing in the world. At an ideological level I’m opposed to ideology. Every ideology ends badly. I write for the individual. I don’t write about groups or about communities. I write about my life, about people I know, about my world, about the street I live on.”

“Heroin, the Immortality of the Soul,’ was published about 17 years after his second book of poetry. “I write when I have something to write and I publish what I think is worthy,” he says about the long time intervals. “I’m not one of those people who get up in the morning and say, ‘Okay, I’m going to sit and write a poem.’ I’m not capable of that. I have to feel that there’s something inside me that wants to be said, something that wants to emerge and express itself.”

Abandoning the weak

“B’Hesed,” an anthology of his work, also sketches Greenberg’s development as a poet. “Each one of my books is very different,” he says. “The first was shy and restrained, one could say, the second was very solid in form and very complete, and the third book is the one in which I take the most freedom for myself, both emotionally and in terms of form. I’m more liberated.”

“Heroin, and the Immortality of the Soul” has the following dedication: “May this book be a memorial / to Alaa a-din Schweike / for whom the doors of the world were slammed in his face even before he saw the light of day / and who has yet to enter the World to Come.”Open gallery viewMK David Bitan.Credit: Ofer Vaknin

The book, which mourns Alaa’s death, is suffused with pain. Yotam Reuveni wrote in a critique published in the Haaretz books supplement Sfarim in 2018: “It’s a book that’s hard to read (although it’s very readable), one finds no rest or any optimism, but nobody who picks is up will put it down before finishing it. It’s a heartbreaking book.”

How did the relationship with Alaa cause him to look at drug addicts? “People think that drug addicts are people without emotions. It’s exactly the opposite. They are people who are flooded with emotions who need large quantities of drugs in order to dull that emotion. Beforehand, I frankly admit, I saw them as inhuman creatures, as though their humanity had been lost. I didn’t even feel sorry for them. When you see them crouching, descending into the influence of a drug, it’s hard to see the human being within. Because of Alaa, I started to see the person behind the addict, and it’s heartbreaking. These are the most sensitive, the most fragile, the most delicate people, who simply don’t fit into this world, this rat race, and don’t know how to deal with it.”

And what does he think of the homeless now, after meeting Alaa? “That people don’t understand the significance of being homeless,” he answers. “The poem ‘For you, the sleeping ones’ was written for them. I think that a society that abandons the weak is a society that has no moral right to exist. Here, the State of Israel has deteriorated badly. This has become more prevalent in Israel as of the 1990s. It tells us about the rejection of the weak in society. Today elderly people die at home alone, hungry, childless. For the past 30 years the State of Israel has served the wealthy and abandoned the weakened populations.”