After all-too-common acts of police brutality against Black women, the hashtag #SayHerName” now peppers social media timelines. The phrase, codified in 2014 through Kimberlé Crenshaw’s Say Her Name campaign, serves as a long-standing reminder that Black women are often erased as victims of police violence. Following the March 13 shooting death of 26-year-old EMT Breonna Taylor by Louisville police while she slept unarmed in her bed, that’s exactly what her family wanted: for the world to remember her story and know her name.

“I want [people] to say her name,” Taylor’s mother Tamika Palmer told the Washington Post and The 19th in a joint interview in June. When a trio of police officers invaded the apartment Taylor shared with her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, she was little more to police than an excuse for a drug search. They entered her apartment, wearing plainclothes and reportedly without announcing themselves, under a no-knock warrant to search for two drug suspects — neither of whom lived there. When Walker, defending himself against a home invasion, shot once at one of the officers, they returned fire with over 20 rounds, shooting Taylor eight times.

“I’m just getting awareness for my sister, for people to know who she is, what her name is,” Taylor’s younger sister Ju’Niyah Palmer, who’d been tweeting about Taylor, added. While the names of Black men and boys who fall prey to racialized violence are often well known — think Mike Brown, George Floyd, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, Botham Jean, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin — women who suffer similar fates, like Sandra Bland, Shantel Davis, and Mya Hall, are frequently overlooked.

After videos of the deaths of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery went viral in May, arrests and indictments came swiftly for their killers. But Taylor lacked nationwide recognition, and it had already been months since her death. In June, however, amid the national protests against racist police violence, that changed: “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” became a widespread social media cry.

Since then, Taylor has become a household name. Her death and an increased awareness of the no-knock warrant practice that allowed cops to enter her residence unannounced have garnered international media attention and become the subject of a broader conversation about police brutality and social justice — especially when it comes to women who’ve been killed by officers.

And that attention has come with ongoing activism and calls for proper redress for her death. Protests in Louisville are ongoing, with residents demanding justice for Taylor as the investigation into her death grows. Online support has boosted the GoFundMe fundraiser for Taylor’s family to over $6.5 million. Members of the WNBA recently began wearing the names of victims of police brutality on their warm-up outfits, prominently recognizing Breonna Taylor as the woman whose death sparked the change. For the first time in history, Oprah Winfrey removed her own photo from the cover of O magazine and pictured Taylor instead. Winfrey also placed 26 billboards featuring Taylor’s image across Louisville, one billboard for each year of Taylor’s life. Everyone from pundits to politicians is now saying her name.

By any metric of success, Taylor’s family have gotten their wish: Their calls to keep Breonna Taylor’s name alive have been heeded.

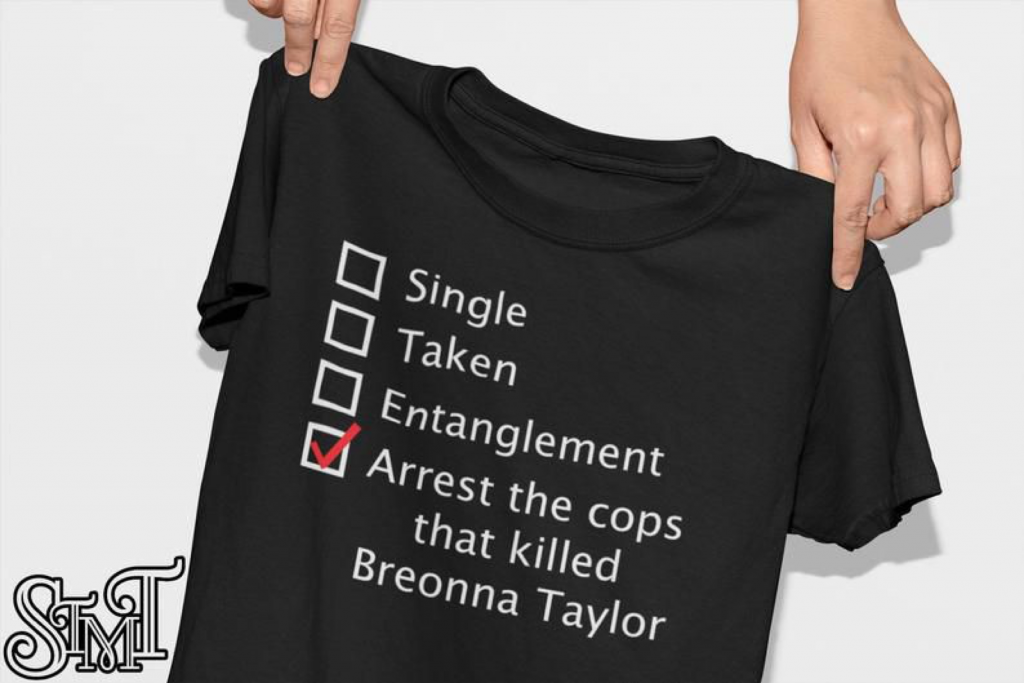

But alongside the prominent spread of “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor,” we have a new, perplexing quandary. On social media, regardless of intent, her supporters often seem to blunt the impact of their message by treating phrases like “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” and “it’s a great day to arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” almost as a punch line. Often, social media posts that start out with unrelated content will suddenly feature Breonna Taylor’s name — like a now-infamous “sideboob” Instagram post by Riverdale actress Lili Reinhart, for which Reinhart swiftly apologized. All the while, the justice these well-meaning supporters want for Taylor has gone undelivered, and authorities continue to encounter hurdles in her investigation due to a lack of police cooperation. This week marks five months since Taylor’s death, and while one of the three officers involved in the incident has been fired, the two others have been placed on administrative assignment and no arrests have been made.

The online agitation over saying Breonna Taylor’s name has clearly been useful as a way of spreading the news about her death, but is saying her name really enough to create real change? What happens when a name becomes the only thing people are saying?

Taylor’s name has partly become a meme

As a call to action, “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” is a ringing demand for justice laid out in perfect iambic pentameter. It’s succinct, angry, and to the point. It became, in no time at all, a ubiquitous slogan for one of the most prominent flashpoints in the energized Black Lives Matter movement.

But almost as soon as Taylor’s name went viral, the call to action became something closer to a meme-fied catchphrase, with many social media users turning calls to arrest Taylor’s killers into a kind of structural gimmick.

The catchphrases and memes based around Breonna Taylor’s name rapidly eclipsed all discussion of the alarming and disturbing circumstances surrounding Taylor’s death — and it didn’t take long for people to notice and begin commenting on them.

Indie merchant platforms like Etsy and Teepublic have seen an explosion of for-profit merchandise exploiting Taylor’s name. Breonna Taylor face masks are a particularly hot item on both websites. Of the 10 random Etsy merchants I browsed, only one promised to donate an unspecified portion of sales proceeds to the Taylor family’s GoFundMe. Another two promised that “some” of the proceeds from sales would support the Black Lives Matter movement or community empowerment in a vague way. One store sold Breonna Taylor and BLM face masks alongside Blue Lives Matter face masks without any acknowledgment of their ideological contradictions.

It’s easy to take in all this commodification and performative social media action and come away feeling jaded. Cate Young would know: She was one of the first people to devise a campaign to raise awareness for Taylor. A freelance culture critic, Young created the wildly successful Birthday for Breonna website, which outlined a hybrid campaign of online action, social media activity, and IRL activism. Actions ranged from donating to the Taylor family’s GoFundMe to sending birthday cards to Kentucky’s Attorney General on June 5 — what would have been Taylor’s 27th birthday.

“My initial worry when I was coming up with this list of items was that no one would care,” Young told me. “That was part of why I decided to do [the website] in the first place, because it was around the time of George Floyd’s murder and the protests in June. And it felt frustrating to see her name not come up in any of the stories and to see the way that she was being erased in real time. And I worried that nothing would come of the campaign, and no one would care and no one would participate.”

But Young’s worries proved unfounded. In fact, social media was initially the boon her campaign needed.

“This is not a case where I can say that people didn’t care or didn’t mobilize, ’cause they did. They absolutely did,” she said. “People sent stacks of letters, got their families involved. People started baking cakes for her birthday and selling slices, donating the proceeds to the Louisville Bail Fund, things of that nature. People started getting creative, which was really encouraging.”

The online agitation seems to have helped people understand what happened to Taylor; in fact, Google Trends shows that searches for “Breonna Taylor” spiked sharply during the first week in June. That’s the week of Taylor’s birthday and the week that “Arrest the cops …” began to gain widespread attention from celebrities and the media.

But Young quickly realized, as the investigation into Taylor’s death lost momentum and continued to encounter roadblocks, that online activism wasn’t enough to effect meaningful change.

“[The campaign] was successful, thankfully,” she said, “but I think despite everyone’s best efforts and involvement, there still has been very little movement. The officers still have not been reprimanded in any real way. It’s since come out that the warrant that was executed on her home was part of a larger gentrification strategy in that area. And not much has changed, unfortunately, despite all the work that went into it.”

In a piece for Jezebel outlining the litany of ways in which Taylor had been meme-fied across social media, Young decried the “Arrest the cops” catchphrase as part of the problem. “Absent any specific call to actions,” she wrote, “‘Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor’ became a clarion call, divorced from Taylor’s life and image—the newest virtue signal of choice, one that defies the current conversation around the abolition of police and prisons.”

If that conversation feels different in Taylor’s case, it may be because it’s being had by new people. Whenever political concerns take over social media, memes are often used as a way to cope with the news and as ways to spread a message to the uninitiated — who then make memes of their own in order to participate in the conversation. It’s likely that many people who are talking about Taylor’s death now have little idea what ideas like “abolish the police” or “defund the police” really even mean.

Nearly a full six months after Taylor’s death, with the investigation into its circumstances seemingly stalled, Young’s frustration seems easy to understand. The online pressure for justice seems to have had little effect on Louisville authorities. And the original reason that the #SayHerName hashtag generated momentum in the first place — to draw attention to violence against Black women — seems to have been drowned out by all the social media noise.

The memeification of Taylor’s name is still serving an important purpose — up to a point

Not everyone is as quick to write off the importance of the call-to-action-turned-catchphrase. “I feel that we’re in a place where we’re crying for help,” Ardre Orie told me. “And so when you get to that place of desperation, [you reach for] any megaphone that can be leveraged.“

Orie is a former educator who runs a vanity press focused on elevating Black voices, so I wanted to ask her about the potential usefulness of social media hashtags and slogans in this case. She told me that tweet-ready phrases can be helpful in terms of awareness-raising, but also just in terms of letting people feel like they’re contributing.

“There are people who are misinformed and miseducated, but they want to do something. And they’re using the hashtag and creating it in ways that are placed behind sentences that start off as, ‘My favorite movie …’ or, ‘Guess what I think about X, Y, and Z,’ that then [end with] “Arrest the cops that killed Breonna Taylor.’”

These lighter messages are probably fine by themselves, Orie indicated. But other uses, such as jokes or “anything that demeans the fact that we’re talking about a life,” she said, were less helpful. “I definitely don’t sit in agreement with that and I don’t condone it, but I also do not fault people for trying to scream from the rooftop to realize justice in an unjust society.”

Young also acknowledged that between the protests, the pandemic, and whatever else 2020 is hitting them with, many people just might not have the energy to devote more of their attention to Taylor outside of an Instagram post or a tweet. Still, she said, “There is part of me that wishes that we could kind of continue the momentum in a way that didn’t lead to dilution of the most radical ideas.”

Orie also told me she recognizes that public discussion of Taylor’s death hasn’t done nearly enough to generate awareness of all aspects of her story, and the way that misogynoir within the justice system contributes to violence against Black women.

“When you think about the implications and the messaging, because of the fact that nothing is being done, that gives a very loud and clear message to Black women in this country about the value of our lives,” Orie says. “If it is possible for you to be lying in bed, minding your business, not doing anything wrong, be a productive member of society … and then for your life to be unjustly taken and nothing to be done about it, it speaks great volumes. So there has to be another way to counter narratives like that so that that does not become what you believe about your life.”

Ideally, hashtags like #SayHerName should have helped to provide such a counter narrative — but their impact has been diluted. In fact, even the hashtag #SayHerName itself was subsequently overlooked after its initial creation, as it became co-opted into broader ongoing social media trends like #SayHisName and #SayTheirNames.

“It’s sad to say but [the] reality [is that] Breonna Taylor was a Black woman,” the Louisville-based poet and racial justice activist Hannah Drake told me. Drake has been active in the protests and the community conversation since Taylor’s death. “Black women will always have to fight to be heard and seen, even in death.”

Still, she told me, “I believe a broader conversation is [starting to] happen. This is much bigger than the three officers. It is how all those in positions of legal power conspired together, from [officer] Joshua Jaynes providing false information to obtain the [no-knock] warrant [to] Judge Mary Shaw signing five no-knock warrants in less than 15 minutes.

“We cannot just look at one thing,” she cautioned. “We must look at how all of these elements worked together to lead to the murder of Breonna Taylor.”

Social media, however, favors short witticisms and attention-grabbing, succinct messaging — not these kinds of lengthier explanations. “Arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor” is pithy and clear. “Breonna Taylor died because of systemic racism and a growing power imbalance between police and civilians” is not. It’s not easy to lay out the entire case in 280 characters on Twitter.

What if arresting the cops is not the best idea?

Perhaps another part of the trouble with figuring out how best to deploy social media in the face of cries for justice is that there’s little consensus on what justice actually looks like. Young told me she’d been second-guessing whether seeing the cops arrested is even the course of action she wants to endorse.

“In the time since that campaign, I’ve kind of been struggling on my own about what justice means in this case, because … fitting with the literature around police and prison abolition, I don’t necessarily know that arrest for her killers is the right course of action. I’m just figuring out for myself what feels just and how that can be achieved.”

Young added that she’d also started to question whether she really believed in abolishing the police, another common protest demand. “I feel like for me, at least moving towards an abolitionist framework feels like excusing her death on an emotional level. But I think on a practical level, if we are really trying to divorce ourselves from the carceral systems that we know are harmful, it means not feeding more people into it. Even people who have harmed us, and even cops.”

Within this conversation, she told me, the people who are calling for Breonna Taylor’s killers to be arrested fall into two camps: the activists and the performers.

“I think there is definitely a distinction between the people who sincerely believe that arrest is the right course of action and people who want to appear to be doing something,” she said. “For the former group, the issue is [less about] discouraging them from using [the catchphrase]. I’m… asking them to consider what arrest accomplishes.”

Orie emphasized that it’s unlikely advocates for justice will ever reach a unified position about what justice looks like. “I don’t think that there will ever be full agreement,” she said. “I think we have to acknowledge that this is chaotic, and so you won’t have everyone in agreement with how to bring about justice, with how to make it right, with how to change the narrative or control the narrative at all.”

Still, despite not being sure what proper justice will ultimately look like, she cautioned, that’s no reason to jettison the social media push to remember Taylor. “I think that the bottom line is that in this instance, when we are saying her name and are keeping it at the forefront, I don’t see it to be a negative thing because there have been many scenarios where the names are forgotten … I don’t think that it’s a bad thing that we are saying the name because in that space, that is how more people learn about what has actually happened.”

Undoubtedly, the best way to support Breonna Taylor and other victims of police brutality is to take your support offline. “You tweeting [‘Arrest the cops …’] to me doesn’t get them arrested,” Young stressed. “That doesn’t actually make a material difference in that case or increase the likelihood that those men will be arrested.”

That’s why her campaign emphasized real-world actions. “I specifically wanted physical letters sent to those offices,” she said, “because it’s very easy for these officials to get off Twitter for a day and block a hashtag or filter their tweets. That stuff is easy to do. … They don’t have to see that stuff if they don’t want to.”

A write-in letter campaign to local authorities handling the investigation, she said, was much harder to ignore. “[State and local officials] may never have read any of the thousands of letters that arrived to them, but they still have to physically deal with them. That’s an inconvenience that makes us an issue that they have to think about because it’s a physical thing in their space.”

Drake, who’s been in Louisville working with community advocates for justice, has a far more localized perspective. She and other activists are focused on specific concrete steps that seem far removed from the online conversation. “Locally, I think people are saying ‘arrest the cops that killed Breonna Taylor’ and that’s the statement,” she said. “There is no meme. There is no list of mundane activities. That’s the message. Even more so, arrest Joshua Jaynes, Brett Hankison, Myles Cosgrove, and Jonathan Mattingly. They don’t get to hide behind ‘arrest the cops.’ These are their names. They are the ones responsible for the death of Breonna Taylor. That is the message and we will not shift from that. Justice for Breonna isn’t a meme. We want it to be reality.”

It’s through the efforts of local activists, Drake noted, that no-knock warrants were swiftly banned in Louisville after Taylor’s death; now they’re figuring out what’s next. “We are just starting to really ask, ‘how did this happen?’” she said. Meanwhile, the protests for Taylor continue.

Drake has simple advice for those who actually care about justice for Taylor — and it goes right back to the beginning of the conversation: “Share Breonna’s story. Say her name. Keep her trending. Do not let her be forgotten.”