As I eagerly await Spotify’s year-end report on my most-played songs of 2021, I wonder which ones will remind me of my summer in New York City—of off-pitch Karaoke Television with friends, or the distinct “popping” sound of a pigeon being run over by a taxi not more than two feet in front of me. Though I thrived amid the frenzied surprises of the city, I also found sudden moments of quiet solemnity while sketching inside the many art museums of the Big Apple. One of those museums was the Noguchi Museum, established in 1985 by its namesake Isamu Noguchi, a Japanese-American sculptor who is also well known for his landscape architecture and modern furniture designs such as the iconic Noguchi table.

Although my primary motivation for going to New York was to study art and how it intersects with nuclear weapons history and policy, as part of a fellowship from Rice University and the Prospect Hill Foundation, I did not expect to see nuclear issues front and center in any of the major museums or galleries. But the Noguchi Museum, with its special exhibit Memorial to the Atomic Dead, proved to be a pleasant surprise. Before the show closed in mid-August, I had several prolonged conversations with museum staff, including senior curator Dakin Hart and assistant curator Kate Wiener, about Noguchi’s life and legacy.

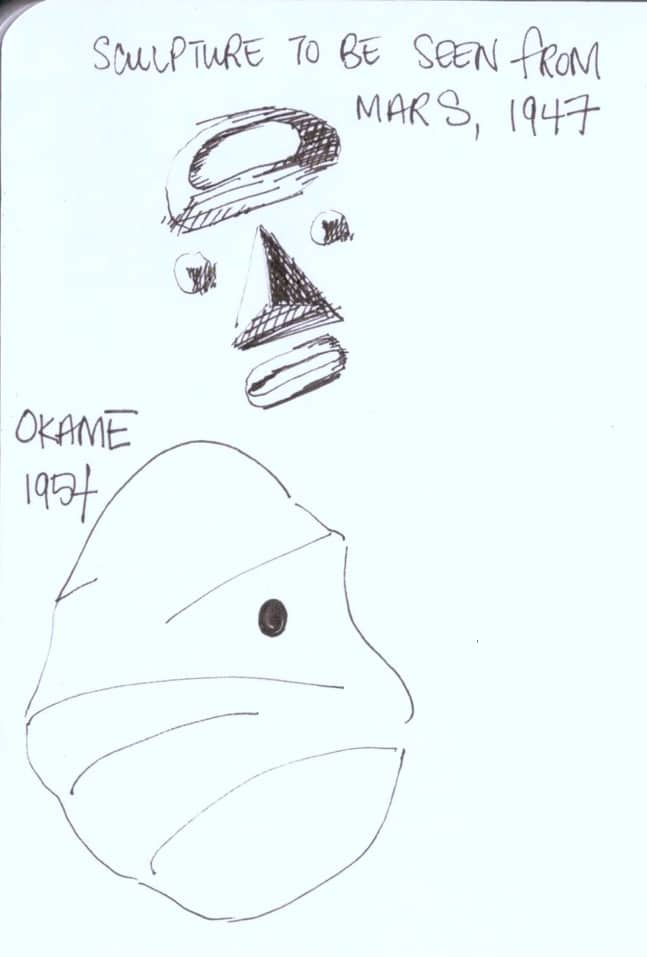

I strolled through the museum five times within a single month, sketched some of the pieces from the exhibit that held my attention most captive, and bought multiple books about Noguchi and his work as I confronted an important question facing those of us studying nuclear weapons today: How will the victims of atomic warfare continue to be remembered and honored in the future? Perhaps “art” is an obvious answer from an art student, but my time in the Noguchi Museum, combined with my first semester in a Master of Fine Arts program, has helped me appreciate how art can help people “un-forget” the legacies of the hibakusha (or “bomb-affected people”) of Japan.

“Not quite belonging.” Isamu Noguchi was born in the United States in 1904 to a white, American mother and Japanese father. His father, Yone Noguchi, was a well-known Japanese poet who moved back to Japan before Isamu was born. His mother soon followed in 1907, taking Isamu with her and raising him in Japan until he was 13, when he moved back to the United States to finish school. After graduating from high school, he entered Columbia University with the intention of studying medicine, but dropped out after just one year to pursue artmaking professionally.

During his career, Noguchi studied under renowned sculptors, including Constantin Brancusi and Gutzon Borglum, won a Guggenheim Fellowship, and traveled the world to further his artistic studies. Over the years, his works slowly gained acclaim.

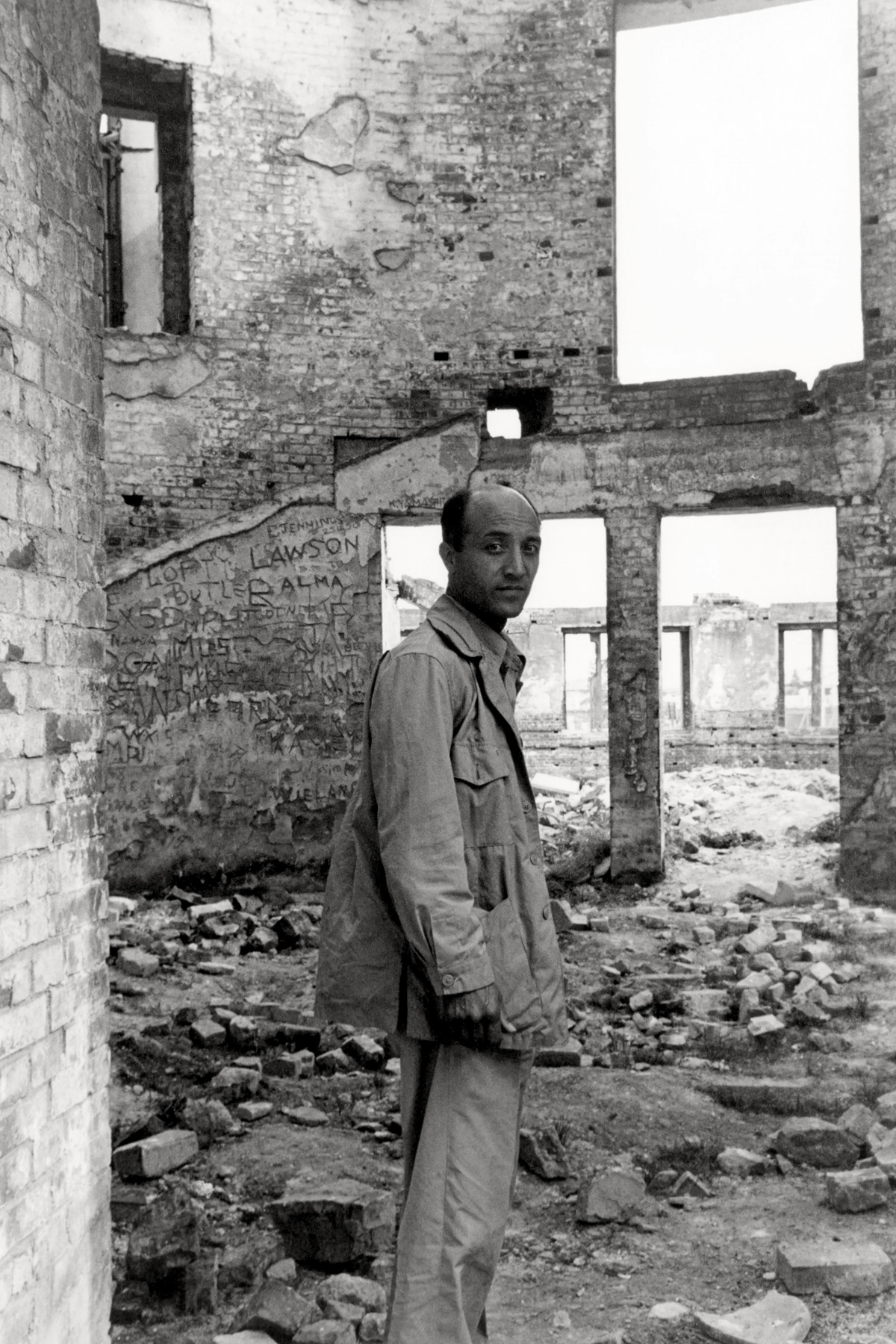

Though he was mixed-race, Noguchi often seemed to have found himself a “seat at the table,” as Hart put it. He spoke before Congress after President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the internment of many Japanese-Americans, most of whom were American citizens, in 1942. Noguchi then traveled to Poston, Arizona, in May of that year to voluntarily enter one of the Japanese internment camps, with the hope of turning it into a thriving center for arts and culture. He was shocked to find himself treated like any other Japanese prisoner.

In an essay for Reader’s Digest that was never published, Noguchi wrote that “a haunting sense of unreality, of not quite belonging, which has always bothered me, made me seek for an answer among the Nisei.” (Nisei are the American-born children of Japanese-born immigrants.) At the camp, though, he felt isolated from other Nisei who believed him to be a government spy. The alienation Noguchi faced continues to be a common experience for many Asian-Americans and is now referred to as the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype.

Noguchi left Poston in November 1942, deeply affected by what he experienced. Though he was outwardly disillusioned and claimed to want little to do with politics from then on, it’s clear from his work that he found it nearly impossible to separate art and politics. After the atomic bombings of Japan, he explored his personal relationship with weapons of mass destruction, as someone whose identity was tied to both the perpetrators of violence and its victims.

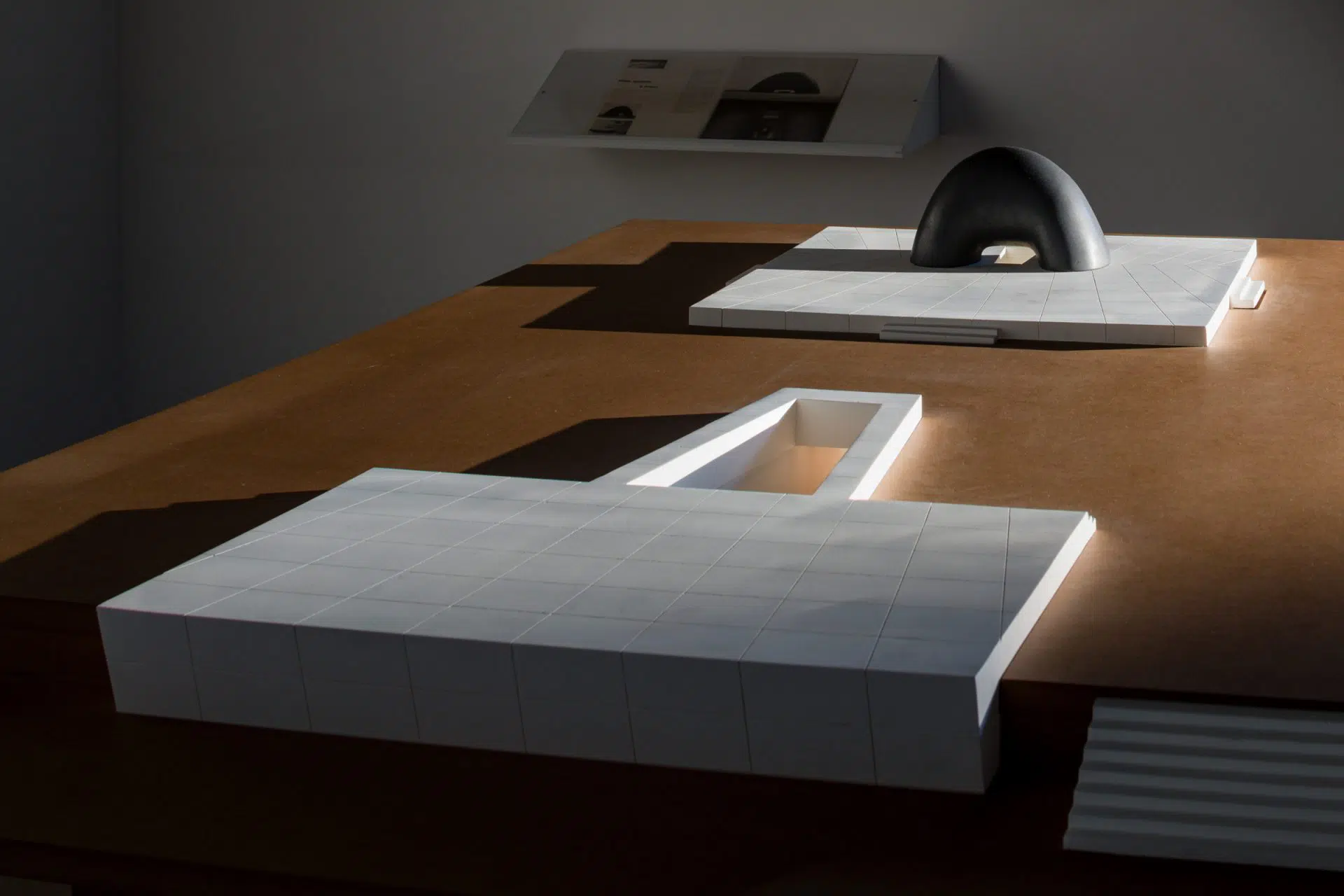

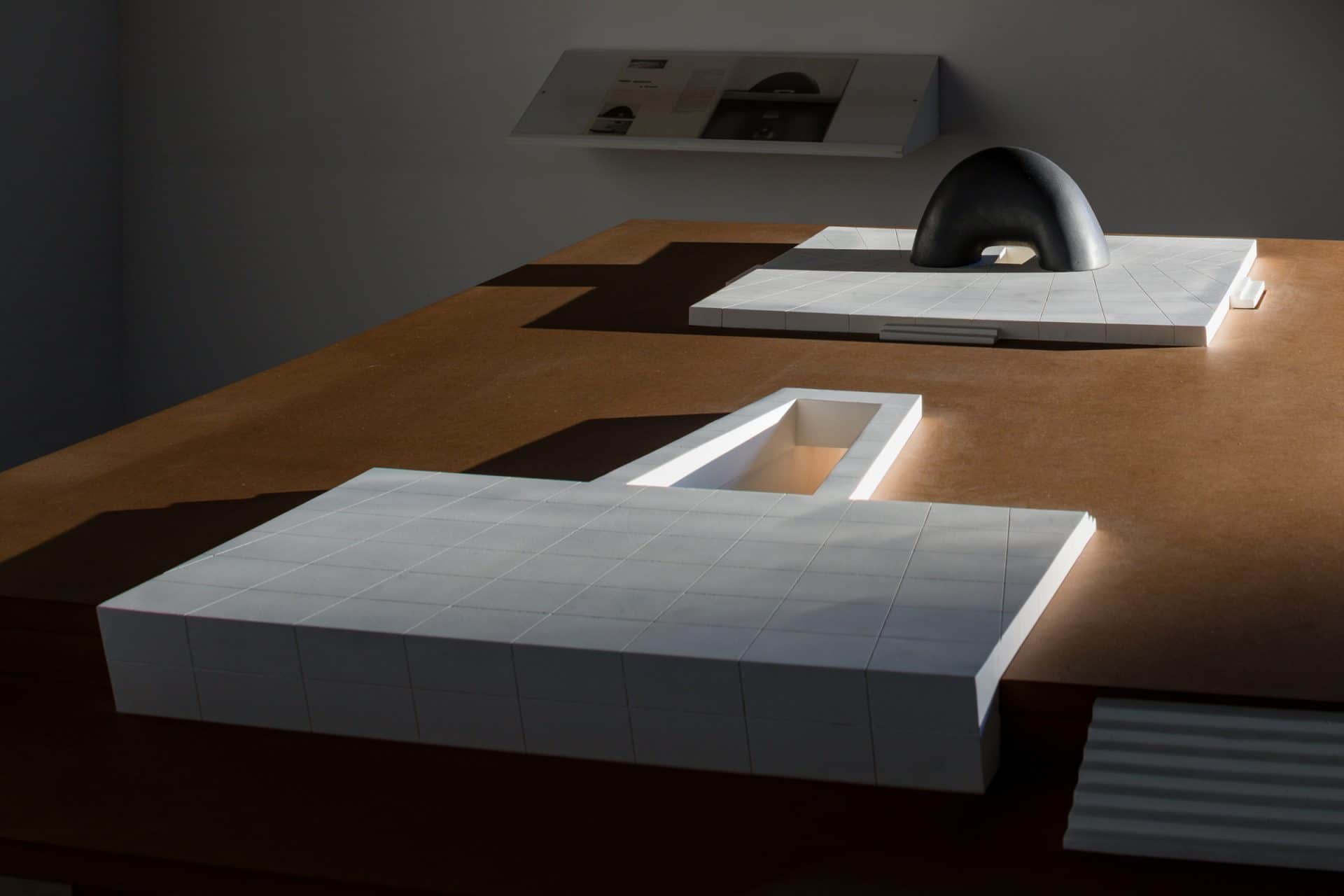

In 1951 he submitted a proposal, later to become the centerpiece of the exhibit Memorial to the Atomic Dead, for a memorial to be built in Hiroshima to honor those who died in the blast in 1945. Though the city rejected Noguchi and instead chose a design hastily drawn up by his close friend and colleague Kenzō Tange, Noguchi continued to revisit his own proposed model and once was even in talks about erecting his structure on the National Mall in Washington, DC.

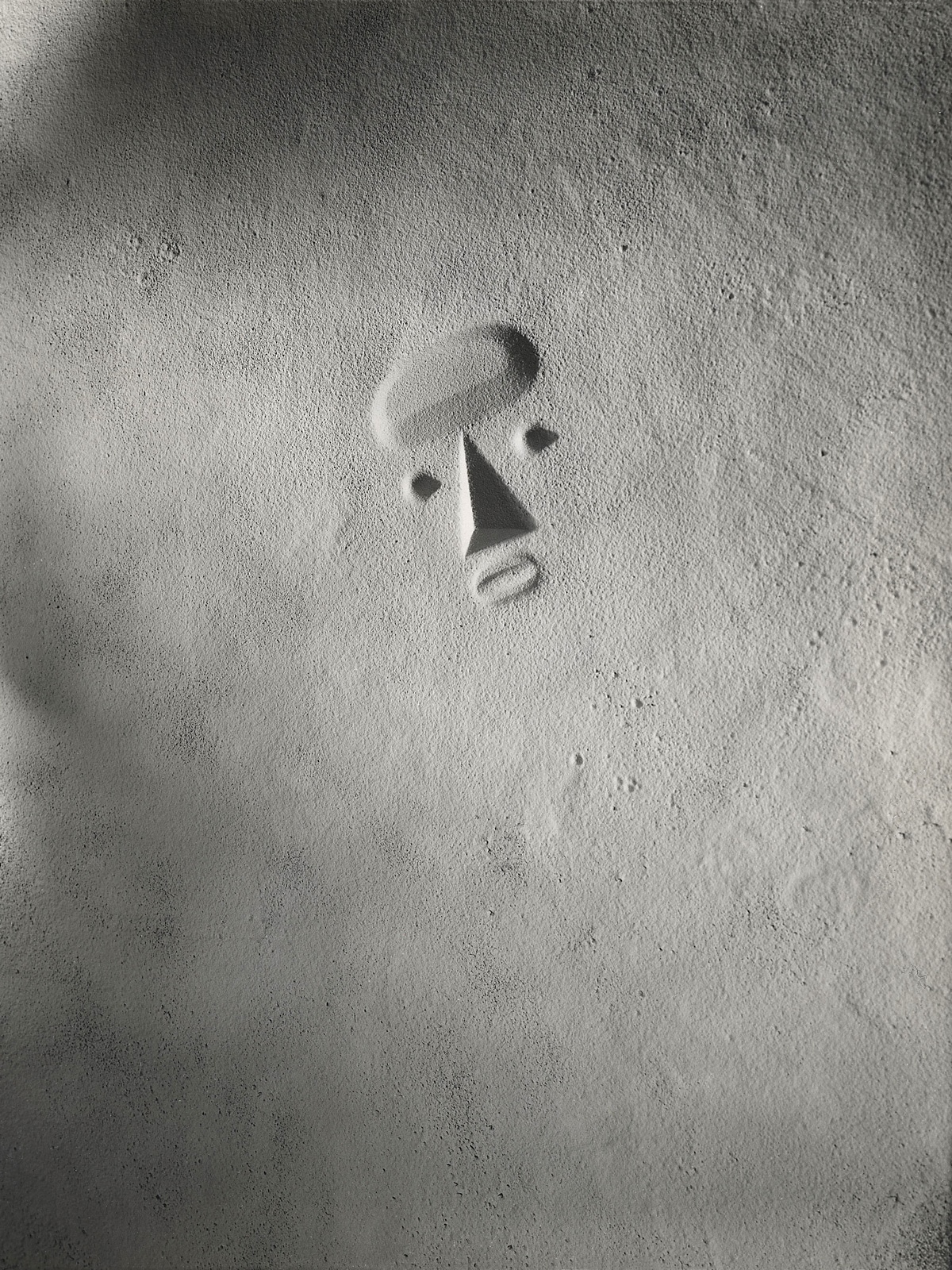

Before he passed away in 1988, just three years after opening his museum, Noguchi made a variety of other works that explored the concept of legacies—and specifically those of nuclear weapons and its victims—many of which were featured in the recent exhibit. One piece that stood out was Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars (1947). The original concept of a 10-mile-long earthwork with an almost geometric configuration of a human face was never fully realized, but a photograph of the model formed in sand lives on. It was meant to be “an eternal reminder to the rest of the solar system that the planet Earth, seemingly bent on self-destruction, once had its civilizations,” according to the catalog for a traveling Noguchi exhibition. This idea for a memorial was a response not only to Noguchi’s deep fear of nuclear annihilation but also perhaps to the death of his father that same year.

It remains a highlight for me because of its cosmic scale and because it is dedicated to people with whom Noguchi both is and is not intimate. To memorialize and carry on the legacies of those we knew deeply and personally is one thing, but to do so for people we have never met, such as the hibakusha, requires recognizing a universal humanness. Easier said than done at times, no?

Connections across time and space. As an activist with a special focus on nuclear weapons policies seen through a social justice lens, and as an artist currently pursuing an MFA in Community Arts from the Maryland Institute College of Art, I find myself lost in a near-existential spiral when I recall my experiences at the Noguchi Museum’s exhibit, the conversations with its curators, and how they combine with my own idiosyncratic hyperfixations. I often return to the same two questions: What kind of legacy do I hope to leave as an activist and artist? And how might I and others best cultivate and honor the legacies of the hibakusha?

Noguchi very much took matters into his own hands by creating his art and erecting his museum. But because he is no longer with us, the responsibility for his legacy now lies almost entirely in the hands of the museum staff. And so we begin to see connections across continents and generations. Almost like a game of “telephone,” Noguchi’s experiences as a mixed-race Nisei who lived during extreme anti-Japanese sentiment are shared through his art, through his museum and its staff, and now through me to you. Noguchi’s work serves as a link in this chain between his own experiences and those of the people he met throughout his life, such as the hibakusha.

Thinking about all of this, I once again became acutely aware of my presence in a majority-white America as a Chinese-American during a time of extreme anti-Chinese sentiment. Thus far the legacy of COVID-19 is one of worldwide upheaval, and I am processing my experiences, and the experiences of others shared with me online or in real life, through my art.

I’d never go so far as to say I can make a name for myself as big as Noguchi’s by the time of my own death, but if my work could contribute even marginally to helping my society reconcile with its history of colonization and exploitation, sugar-coated by the US compulsory-education system, I’ll feel my choice to abandon a potentially lucrative medical career for that of a “starving artist” was well worth it.

The legacy of hibakusha. Art is a powerful form of communication. It’s something that can be both visceral and cerebral, and sometimes so complex and subtle for both the creators and viewers that neither may necessarily be fully aware of its effects.

In 1945, Japanese photographers worked to document the raw brutality of nuclear detonations, despite heavy censorship by both the Japanese and US governments. Many of these photos were later collected in various exhibits and in the 2020 book Flash of Light, Wall of Fire. Hibakusha themselves have used a vast array of artmaking techniques to assist in their own recovery from traumas, such as those depicted in the photographs, and Japanese schoolchildren today sometimes make their own art as a medium through which to process the collective pain and resiliency lingering over Japan since 1945. All of these works then outwardly function to support educational efforts the world over on the inhumanity of using a nuclear weapon.

The hibakusha narrative has expanded over time to include victims beyond the city limits of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—and as far away as the Navajo Nation, which still suffers the radiation effects of uranium mining; the Marshall Islands, where the United States conducted so many nuclear tests that, on average, the equivalent of 1.6 Hiroshima-size bombs was detonated every day for 12 years; Kazakhstan, where the Soviet Union tested its nuclear weapons for four decades; and other places around the world adversely affected by the development and maintenance of nuclear weapons. Noguchi himself considered the term hibakusha to include the victims of nuclear weapons worldwide; he changed the name of his proposed Memorial to the Dead of Hiroshima to the more inclusive Memorial to the Atomic Dead.

I believe my musings on legacies and memorials will continue to gain urgency. The youngest of the first-generation Japanese hibakusha still alive are well into their 80s. When they pass, so too will their stories if we do not take the remaining time we have to listen intently and record meaningfully the firsthand experiences of what could happen if the current near-dogmatic faith in deterrence theory fails.

“Memorials were, for [Noguchi], democratic acts of un-forgetting,” writesNoguchi Museum Board of Trustees member Spencer Bailey. Noguchi himself said, “One does not silently bury the dead building a monument.”

Artists like me are also “building a monument” with our drawings and articles. Hawaiian singer and guitarist Makana was “un-forgetting” when he and filmmaker Kayko Tamaki composed “Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes,” as were the Noguchi Museum curators when they established the special exhibit. Each of us is hoping to pick up the baton from the hibakusha. I wonder what song from Spotify Unwrapped will send me back into rooms of the Noguchi Museum, filled with his legacy and the legacies of those who touched his life.

You can see more work from the Memorial to the Atomic Dead exhibit at the Noguchi Museum’s online archive.

The author would like to give special thanks to the Noguchi Museum, its staff, and, specifically, senior curator Dakin Hart and assistant curator Kate Wiener for the hours spent discussing Noguchi’s work and life. Additional thanks to the museum for financial support for the author’s work and research. Finally, more thanks to Rice University’s Wagoner Fellowship, The Prospect Hill Foundation, Demi Guo, and Lorelle Pais for their unwavering moral, logistical, and financial support.