Jan. 9—For most of her career in Portland Public Schools, Julia Hazel was either the only teacher of color or one of just a handful in the schools where she worked. She often felt underestimated.

“I’ve had people shocked I have an opinion or that I was intelligent or that I had a proposal to say, ‘No, let’s do this a different way,’ ” Hazel said. “I’ve had people surprised I was a teacher. There’s an assumption you must be an ed tech or a parent because our teachers are white.”

Hazel is hoping to change that perspective in her new role supporting and serving as a resource for other teachers and staff of color. She has a newly created job in the school district as its director of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) career pathways and leadership development.

The position was created as part of a $2.9 million investment in equity in the school budget this year as Portland, like other school systems in Maine and New England, looks to increase teacher diversity.

“Certainly the events of the last few years have promoted and prompted that conversation to a greater extent,” said Steve Bailey, executive director of the Maine School Management Association. “I also think the biggest piece is we’re seeing our enrollment change in a number of communities so people are stopping to think about, ‘We need to see what we can do to provide equitable opportunities for all our students.’ “

Nationally, about 21 percent of public school teachers are people of color, compared to about 53 percent of students, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In Maine, where about 88 percent of students are white, the state doesn’t track the race of teachers and staff.

In Portland, the state’s largest and most diverse district, 48 percent of students are not white, compared to 6 percent of teachers and 11 percent of the overall staff.

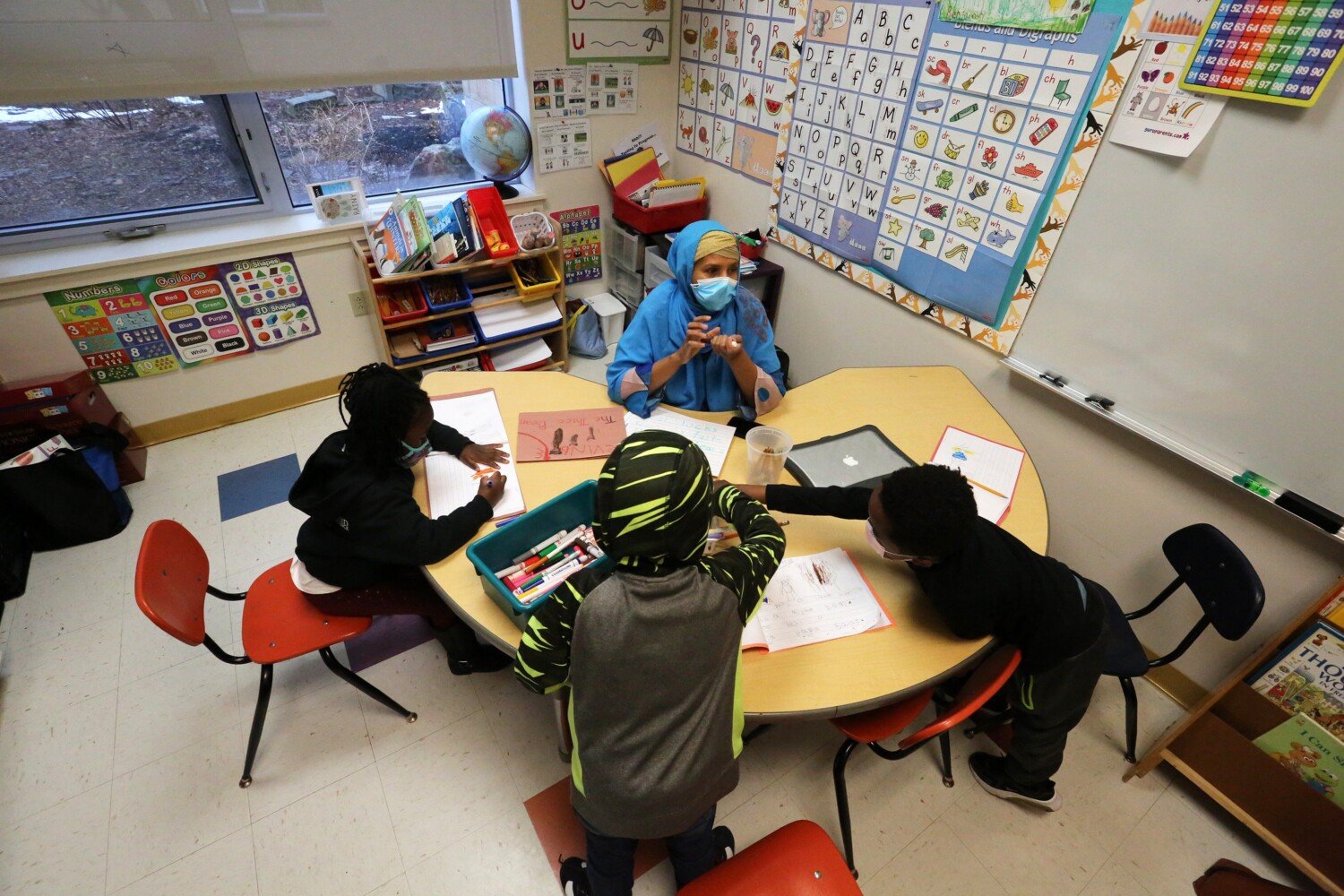

Hana Tallan is a kindergarten teacher for English language learners at East End Community School and has worked in the district since 1996. She said she appreciates recent efforts to support and promote staff of color.

“Realizing we can’t just keep the diverse staff in low jobs when they’re qualified for higher positions is new,” said Tallan, who is from Somalia. The district has long had staff with a lot of training elsewhere, she said. “Some of them had PhDs in their home countries, but they were hired as language facilitators. … We were sort of happy to help the community and the students that need it, but we lost a lot of staff because they couldn’t move up in the system. That’s what’s new now: equity in people.”

Portland schools have won grant money to help in the effort.

Last month, the district got a $175,000 grant from the New Schools Venture Fund, a nonprofit dedicated to innovation in education, to support education technicians in the process of becoming certified to teach. The work will be overseen by Hazel and will benefit educators like Tallan, who worked her way up from a language facilitator to an ed tech to a teacher and is now in classes to get her certification to be an assistant principal.

Tallan became a teacher in 2019. When she decided to take that that step, she said, it took her three years to complete the five courses she needed because the district would only pay for two courses per year. But Hazel said this year’s school budget includes more funding for continuing education classes and the New Venture grant will also help staff get the necessary qualifications to move up more quickly.

About 25 percent of the district’s ed techs are people of color, compared to the 6 percent of teachers.

“We recognize there has been this gap where there was maybe some complacency to allow BIPOC staff to remain in lower positions and (there wasn’t) that recognition that it’s important to have diverse staff in all of the roles,” Hazel said.

Many Portland ed techs are immigrants who were teachers in their home countries but who face barriers to getting fully credentialed in the U.S. The grant will provide for such services as foreign transcript analysis, payment for additional coursework beyond the district’s normal reimbursement, and expanded mentoring and support.

Research shows that having a diverse staff benefits all students. For students of color, having a teacher of color can boost academic achievement and high school graduation and college enrollment rates. There is also evidence that having diverse educators helps students of all races be better prepared to live and work in an increasingly diverse and interconnected world.

But being an educator of color can be isolating in predominantly white New England. That’s where Hazel comes in. A big part of her role will be building a support system through social gatherings, drop-in hours where staff can ask her for help on any front, and a mentoring program that pairs younger staff of color with those who are more experienced.

She’ll also be focused on helping ed techs become teachers and on leadership development. Often as people of color move up in the school system, they still feel “delegitimized” by those who still see them in their old roles, she said.

“We want to create structures of support and pathways to give people all the competencies and experiences they need to feel really prepared for a teaching role,” Hazel said.

Since 2016, Portland has almost doubled its staff of color, though Superintendent Xavier Botana told the school board a year ago that much more work needs to be done to have the district’s workforce better mirror student demographics.

Barb Stoddard, the district’s human resources director, said in an email that she expects new grant money as well as additional funds in the school budget to “substantially move the needle on the diversity of our teacher workforce.” In addition to the New Venture grant, the district received $25,000 from the Barr Foundation and New Teacher Project this fall to analyze the current workforce and its practices.

The grant money from the New Schools Venture Fund will be key in speeding up the process to become a teacher, Stoddard said.

“Typically this process can take six to eight years,” she said. “We’re looking to do it in about three years, while at the same time allowing staff to maintain their employment with us and continue doing the work they love, teaching our students.”

Across New England, diversifying the teaching staff is becoming more of a priority, though the work can be slow. While many districts are now much more focused on diversity in general than they used to be, it’s still mostly the larger, more diverse districts that are focused on staff diversity, especially in northern New England.

“A lot of the focus has been more generally on equity work,” said Don Weafer, a senior associate for the Great Schools Partnership, a Portland-based nonprofit that is working with state education agencies across the region on a project to diversify school workforces.

“If you look in Vermont or Maine, you’ll see positions formed in districts, particularly in diverse districts, where there’s maybe a community director or a community advocate or an equity coordinator that does professional development for the district. Lots of those positions have come into play,” Weafer said. “What I’ve seen less of is programs that specifically target diversifying the workforce.”

Two years ago, the New England Secondary School Consortium, a collaborative representing the education agencies of the six New England states, decided that expanding educator diversity would be one of two priorities for the next few years.

“I think they saw value in a partnership to address the growing chasm between the demographics of students and the demographics of the adults charged with their education,” said Mark Kostin, associate director of the Great Schools Partnership, which runs the consortium.

Last summer, the partnership launched the Diversifying the Educator Workforce Collaborative to create a regional approach. The project is in its first phase, identifying the types of efforts already underway.

And while most of Maine’s diverse student population is concentrated in southern and more urban parts of the state, Weafer said, there are also discussions to be had around attracting diverse staff to rural and less diverse areas, to address critical staffing shortages and prepare students for the larger world.

“There’s a lot of data about how important it is to have a teacher that looks like you for your success in school for students of color, but that kind of obscures how important it is to have a teacher that doesn’t look like you if you’re in a white community,” he said. “We’re preparing kids not to stay in the tiny towns they’re in but to go out into a world that doesn’t look like their tiny town. That’s one thing we try to emphasize. This is important for everybody, not just kids of color or specific communities.”

In Westbrook, where student enrollment is about one-third students of color, Superintendent Peter Lancia said hiring and retaining a diverse staff is a priority for the district’s equity leadership group, even if they don’t have Portland’s grant resources.

“We keep working on it. It’s a priority, but it’s a hard one to tackle and we’re excited to try some new things,” Lancia said. “Just advertising in the Boston Globe or the Washington Post, that’s not going to do it. We have to think differently about recruiting and about welcoming people to our community.”

Last summer, the district revised its hiring process to make sure interviews include questions about equity and diversity and that job advertisements and applications encourage people of all backgrounds to apply.

Lancia said the district is also interested in promoting education careers at Westbrook High School so it can recruit from within, and will soon be hiring a communications specialist to help news of the district reach a larger audience.

“Telling those stories will increase our applicant pools and hopefully lead to that broader pool of candidates that are more representative of our students and our community,” he said.

Tallan, the ELL teacher, said she’s been excited to see staff diversity increase and more of her colleagues of color stay in the school system. But there are still big challenges, including the perception that people of color are taking jobs away from others.

“There is that feeling of, ‘We love to see BIPOC staff but what happens to people who need these jobs? It’s always going to be, let’s hire BIPOC,’ and that’s not the case,” she said.

For a long time, Tallan said, staff of color felt they couldn’t move up in the district or were told they weren’t qualified. She said Botana and his administration, who have made equity a priority, have been instrumental in changing that, as have the calls for racial justice after the death of George Floyd.

“There’s still work to be done in the district, but the dialogue is there. I’m happy we’re discussing it. In terms of where I came from in the district, there was no dialogue around having BIPOC being able to apply and dream about getting a job like this,” she said of being a teacher. “Now, it’s more than a dialogue. It’s, ‘Let’s get going. Let’s do this more.’ “