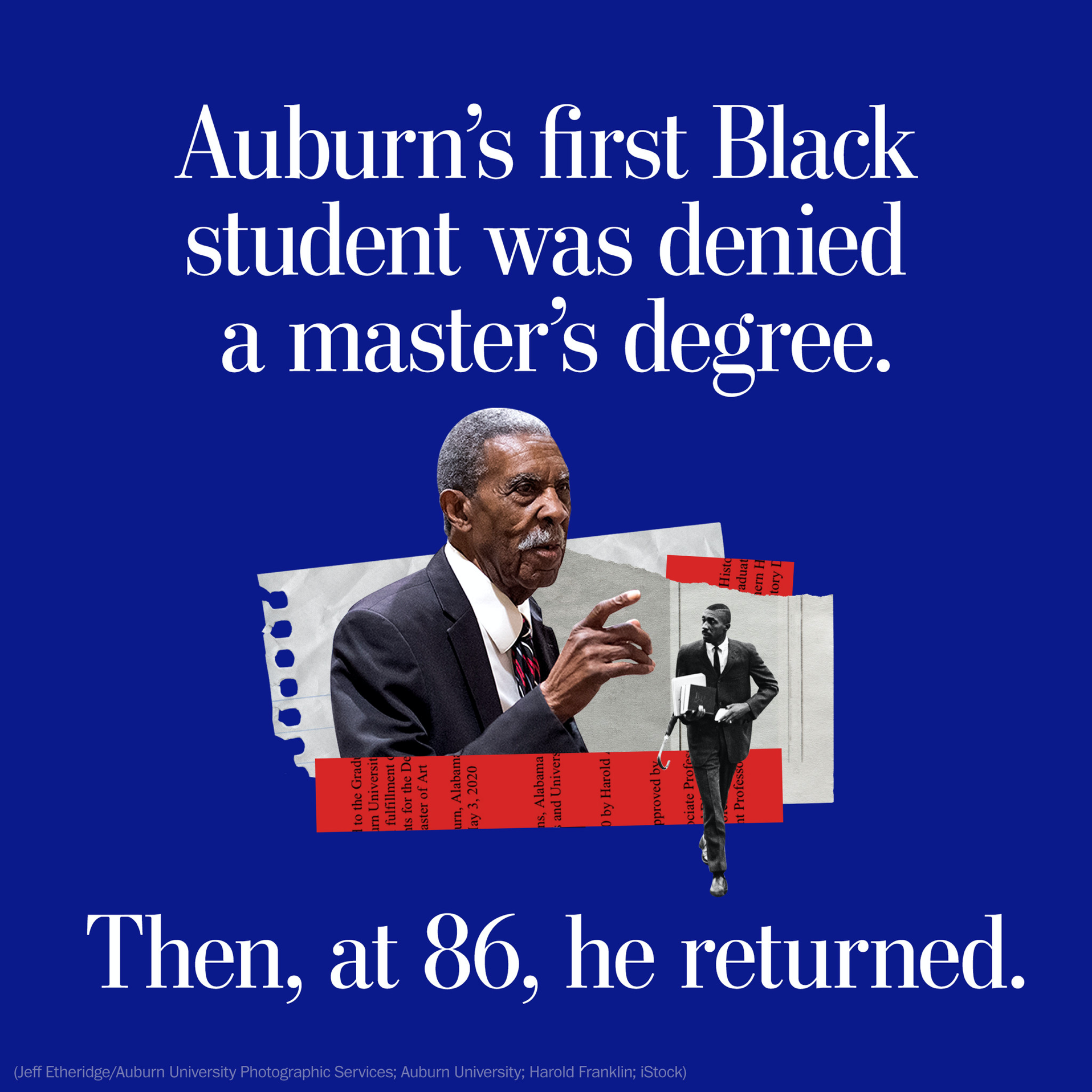

With his hair now salt-and-pepper gray, Harold A. Franklin wore a red-striped tie over an elegant black suit with a handkerchief tucked in the lapel as he walked across the campus of Auburn University.

This was the same campus he’d integrated more than 50 years ago, the same campus that assigned him a wing of a dormitory where he lived alone as the only Black student, and the same campus that denied him the chance to defend his master’s thesis.

“Each time, I would carry my thesis to be proof read, they’d find an excuse,” said Franklin, now 86. “Sometimes, I didn’t dot an ‘i.’ One of the professors told me: ‘Yours has to be perfect because you are Black, and people will be reading yours.’ ”

“I told him I had been to the thesis room and read the theses by White kids,” Franklin recalled. “Theirs were not perfect. I couldn’t understand why they couldn’t accept mine.”

Franklin completed draft after draft. Each was rejected. Finally, he realized he was hitting a stonewall of racism.

“I said, ‘Hell, what you’re telling me is I won’t get a degree from Auburn?’ ” Then Franklin, a tall man who had grown up in the segregated South, told the thesis committee, “To hell with it.” And he left.

Years later, he would earn a master’s in international studies from the University of Denver. He’d return to his home in Talladega, Ala., with his wife, Lilla Mae Sherman, and raise their son, Harold Franklin Jr. He’d teach history — at Alabama State University, North Carolina A&T State University, Tuskegee Institute and Talladega College — until his retirement in 1992.

In 2001, Auburn University celebrated him as the first Black student and awarded him an honorary doctorate of arts. But Auburn never addressed the racism Franklin encountered trying to defend his thesis.

Franklin remembered all this as he made his way on Feb. 19 to Auburn’s history department in Thach Hall. It was just a few weeks before a pandemic would grip the country and just a few months before protests against police brutality and systemic racism would erupt in cities and small towns across America.

Inside the Bond Memorial Library, a committee of four faculty members waited to hear Franklin defend a thesis that had been typed out 50 years ago.

His memory was not as sharp as it had once been, and he was unsure what kinds of questions they might ask. But he was more than ready.

‘Cheated’

Months earlier, Keith S. Hébert, an associate professor of history at Auburn, was reading a news story about Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey (R) wearing blackface during a skit at Auburn more than 50 years ago.

For the story, the reporter had reached Franklin for a comment. In the last paragraph was a quote from Franklin, explaining why he really left Auburn.

Hébert had never heard Franklin’s version. “He’s told the story many times,” Hébert said. “It was our fault we hadn’t picked up on it.”

All these years, Auburn had constructed the narrative that Franklin had just left the university of his own volition. Years later, “Auburn celebrated Harold as the first Black student but never told the full story,” Hébert said.

The university put up a historic marker in Franklin’s honor in 2015 but had never reckoned with what really happened to him.

“During all those commemorations and discussions about integration at Auburn,” Hébert said, “they overlooked the story about this man who was cheated out of the degree he rightfully earned.”

Auburn’s story of racism had been whitewashed in the same way other universities and cities had cleaned up their racist history.

“Atlanta tells the story that it was a city too busy to hate. Auburn has that same story: ‘At least we weren’t Ole Miss or the University of Alabama, where [Alabama Gov.] George Wallace stood at the school house door,’ ” Hébert said. The story was, “Auburn’s president told Wallace, ‘Please don’t come.’ That story whitewashes so much.”

The truth of it was Franklin had to sue the university to gain admission and then had to be escorted onto the campus by armed guards. “Once they got to campus,” Hébert said, “they made a big deal that federal agents can’t come on campus. Harold had to walk 200 yards without police protection to register. Auburn fought integration right down to the last minute.”

Hébert, who is also the director of Auburn’s public history program, decided the history department needed to “make right” what happened so many years ago. Hébert began researching and found the department had rejected Franklin’s initial proposal to write about the civil rights movement.

“Here was a guy on the front lines of Black activism, and the department said, ‘You can’t write that.’ They shoehorned him into writing the history of Alabama State College. He played nice and said he would do that. But after a while, they seemed outright hostile to him finishing it,” said Hébert, who is White and grew up in Louisiana witnessing racism there. “They held him to a different standard because he was Black. It had to be perfect. It was designed to force him to leave.”

Hébert contacted the dean of the graduate school to get the required approval to offer Franklin a chance to defend his thesis. But Hébert didn’t know whether Franklin would agree. And he didn’t know whether Franklin still had his original thesis.

In October 2019, Hébert drove to Sylacauga, Ala., to meet Franklin in his home. After chatting for a while, Hébert asked Franklin, who now works as a manager of a funeral home, whether he still had a copy of his thesis.

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

He did. It was sitting beside a photo of his now-deceased wife.

Hébert became Franklin’s adviser, and they worked to get the thesis uploaded into a computer. “Here’s a guy I’ve talked about in class a lot,” Hébert said. “I’ve taught about his lawsuit in the history of Alabama class every semester. Here, I am hanging out eating lunch with this guy.”

Hébert drove Franklin, who no longer drives, to Auburn, and escorted him inside the library.

“Normally, in a thesis defense, it is the committee and you,” Hébert recalled, “but on this day, the entire faculty attended. The dean of the graduate school attended. A lot of people wished him well.”

Hébert asked Franklin one question. And Franklin launched into an hour-long lecture.

“I asked Harold how did you end up writing a history of Alabama State University for your thesis? It was an open-ended question. I knew it would cover his life story. He quickly went to, ‘I never wanted to come to Auburn anyway. I didn’t want to write this thesis. And then you didn’t accept it.’”

For the next hour, Franklin retold his life story, explaining how he ended up at Auburn walking across a hostile campus in January 1964.

Harold Alonza Franklin Sr. was born Nov. 2, 1932, in Talladega, Ala., one of 10 children to George Franklin Sr. and Henrietta Eugenia Williams Franklin. His father worked at the Alabama school for the deaf and blind. His mother was a teacher and played the piano in church.

“I grew up in segregation, racism and everything else,” Franklin recalled during a telephone interview. “The Ku Klux Klan ran the state. If a White person said I talked back to them, they might lynch me. In fact, when I was growing up, I remember reading a case of the Klan lynching a Black man because a White woman said she didn’t like the way he looked at her.”

Franklin left high school during his senior year to join the Air Force during the Korean War. In 1962, he graduated from Alabama State College. As an admirer of future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, he wanted to go to law school. But Fred Gray, the famous civil rights attorney, convinced him to study history first and encouraged him to enroll at Auburn. When Auburn denied Franklin’s admission, Franklin sued in a case that would become famous.

“Fred Gray was Dr. King’s attorney,” Franklin recalled. “All the civil rights leaders had him. He was brilliant.”

On Nov. 5, 1963, U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson ruled in Franklin’s favor, declaring that the denial of admission by Auburn, a state institution, amounted to discrimination. The judge later ruled that the university was required to provide Franklin living accommodations on campus.

Racial tensions were thick in Alabama that year. Wallace vowed “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” and Klansmen blew up Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four Black girls.

Only a few months later, on Jan. 4, 1964, Wallace ordered troops to Auburn to stop Franklin from attending the university. An FBI agent escorted Franklin to register. “I ended up in a whole wing of dormitory by myself,” Franklin said. “I had the key to the outside door. The only way you could get in the dormitory, I had to let you in.” Being alone in the dorm didn’t bother him much. “I was never a person who liked to be around a bunch of people,” Franklin said.

In classes, White students refused to sit next to him. When he completed his coursework, Franklin wrote his thesis and submitted it again and again.

“They were angry with me because I sued them,” Franklin recalled. “They tried to make it as difficult as possible for me to get my degree from there.”

In the library, the committee listened to Franklin’s story so many years later.

“He had a strong performance,” Hébert recalled. “There wasn’t a dry eye in the house. He told a powerful story.”

Hébert read a statement of apology. “I had read that statement a million times because I didn’t want to break down,” Hébert said. “It was an acknowledgment of past wrongs. I’m part of a society that committed those wrongs. A lot of White people, even my students, say, ‘I didn’t do anything.’ But they fail to understand the privilege White people benefit from and the negative impact on others.”

He was supposed to be awarded his degree at Auburn’s graduation, but the ceremony was disrupted by the pandemic.

Instead, in June, Franklin received his degree in the mail. By then, the country was being consumed by Black Lives Matter demonstrations following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

For Franklin, the clashes felt so familiar.

“I’m glad to see the protests happening now,” he said. “Black people’s lives should matter to everyone else. We are human, like everybody else.” And deserve respect, like everybody else.