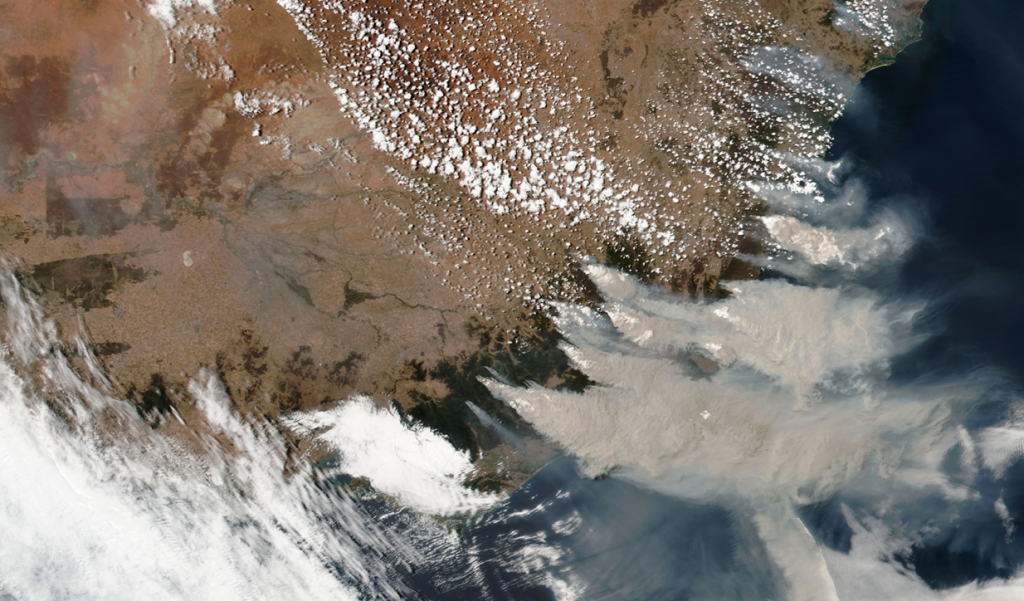

Australia’s disastrous 2019-2020 fire season blew so much smoke into the upper atmosphere that it blocked sunlight from reaching Earth’s surface, potentially causing a brief global cooling effect comparable to a moderate volcanic eruption, new research has found.

In late 2019 and early 2020, raging wildfires in southeastern Australia spawned a rash of rare fire-induced thunderclouds, known as pyrocumulonimbus clouds, or pyroCbs. This pyroCb “superoutbreak,” as scientists are now calling it, injected plumes of smoke into the stratosphere, a layer of the atmosphere that starts about nine miles overhead. There, the smoke plumes spun up their own winds, creating self-sustaining vortexes that circled the globe, in one case climbing to an unprecedented altitude of more than 20 miles in the process.

These smoke plumes did something else scientists weren’t expecting.

Findings published recently in Communications Earth & Environment and presented at the virtual American Geophysical Union (AGU) conference this week show that smoke acted like a planetary shade, reducing the amount of sunlight hitting Earth’s surface for several months.

David Peterson, a meteorologist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory who presented separate findings at AGU detailing the smoke’s persistence in the stratosphere, says the Australian event marks the second “volcanic scale” pyroCb outbreak documented in records going back about 20 years. The first, a large wildfire thundercloud that formed over a blaze in British Columbia, occurred in 2017.

PyroCbs with the potential to impact the climate like volcanoes are new to science, but researchers are racing to learn more about them, motivated by the possibility that extreme fire weather such as this could become more frequent in a warming world. A better understanding of pyroCbs could also save lives, since these clouds are both caused by severe wildfires but can also create extreme weather on the ground, bringing abrupt wind shifts that imperil firefighters and communities.

“The Australian wildfires have basically revolutionized our understanding of the climate-altering potential of wildfires through stratospheric feedbacks,” said Sergey Khaykin, a scientist at the Laboratory of Atmospheric Research and Satellite Observations at Sorbonne University in France, who led the recent paper detailing the Australian pyroCb outbreak’s climate effects.

PyroCbs and volcanic eruptions can both send sun-blocking particles into the stratosphere, but those particles are distinct. Large volcanic eruptions often belch up huge quantities of sulfur dioxide. Once in the upper atmosphere, it can react with water vapor to form highly reflective droplets of sulfuric acid that bounce sunlight back into space. Meanwhile, pyroCbs, infuse the stratosphere with gases from combustion and dark-colored smoke particles such as black carbon, which absorb sunlight and release its energy as heat into the surrounding air.

During a pyroCb event “you have part of the energy which is reflected back into space, very similar to a volcanic eruption” said study co-author Pasquale Sellitto, a scientist at the French climate research organization Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace. “And part of the energy which is blocked absorbed into the plume. And the two things add up to less radiation on the surface.”

Sellitto added that the heat generated by black carbon as it absorbs sunlight makes the surrounding air more buoyant, causing the smoke plume to rise through the stratosphere and be more persistent.

When Sellitto, Khaykin and their colleagues summed up the sunlight-blocking effects of the Australian pyroCb outbreak, they found that the smoke plumes reduced the amount of solar energy entering Earth’s stratosphere by approximately negative 0.2 watts per square meter during the months of January, February and March. This effect, Sellitto says, is on par with moderate volcanic eruptions.

How much the fires actually cooled Earth’s surface during this time isn’t known, although the effect probably amounted to a small fraction of a degree. The recent benchmark for large volcanic eruptions that alter the climate, the Mount Pinatubo eruption of 1991, temporarily cooled the Earth by about 0.4 degrees Celsius, and the Australian event was considerably smaller.

Khaykin says his team plans to investigate this question using different models, but he stresses that it will take “quite some effort” to get a precise answer.

The most popular and interesting stories of the day to keep you in the know. In your inbox, every day.

Smoky surprises

The Australian pyroCb outbreak occurred almost a year ago, and the largest of the smoke vortexes dissipated back in April. But today, smoke from the event is still detectable via satellites, Mike Fromm a fire weather scientist at Naval Research Laboratory, said in an interview.

It’s unclear how much longer it will take for that smoke to dissipate, but it’s already taken “much longer than anyone would have expected,” Fromm said.

“It’s fair to say at this point that the lifetime of this Australian plume in the stratosphere is now the longest of any smoke event, at least in a record we have going back about 20 years,” Peterson of the Naval Research Laboratory said in an interview. “And it’s also on par with some of the largest volcanic eruptions we’ve seen in that same time frame.”

Khaykin agrees. “The effect is still ongoing,” he said. “It’s going to last for one year at least.”

As fire weather researchers continue investigating the impact of the Australian smoke plumes, they are also exploring a wealth of data collected during another pyroCb event.

In August last year, as part of its FIREX-AQ wildfire research campaign, NASA flew a DC-8 research aircraft directly through a wildfire thundercloud as it was forming above the Williams Flat Fire in the Pacific Northwest. As the most detailed scientific reconnaissance mission conducted within a turbulent pyroCb, the data set that the plane collected was “unique,” said Laura Thapa, a PhD student at the University of California at Los Angeles who was working as an intern at the Naval Research Laboratory when the flight took place.

Thapa, who presented her results at an AGU news conference Friday, recently analyzed the size and optical properties of aerosol particles the plane gathered from different parts of the fire cloud. This information, she says, will be useful for modeling future pyroCb events. The plane also collected data on the ice crystals present inside pyroCbs, which could shed light on the clouds’ micro-scale structure and help explain why pyroCbs produce virtually no rainfall.

“It really sets us up to do a lot of cool science,” Thapa said.

An unexpected test of nuclear winter ideas

In addition to spurring basic research, recent volcanic-scale pyroCb events have helped validate theoretical models of nuclear winter.

Computer modeling work has shown that a nuclear conflict could cause giant fires that send vast plumes of smoke into the stratosphere, blocking sunlight and causing global temperatures to plummet. Fromm says that while he used to be a “nuclear winter skeptic,” aspects of what nuclear winter models predict, such as a self-lofting smoke plume that rises through the stratosphere, have been recently demonstrated by nature.

Determining how long smoke from the Australian fires lingers in the stratosphere and how exactly the plumes altered Earth’s climate could shed more light on the planetary consequences of nuclear war.

While humanity will hopefully never face such a scenario, there’s also the possibility that a hotter, more fire-prone world will produce more volcanic-scale pyroCbs. That’s another reason scientists are trying to learn as much as they can about the Australian superoutbreak.

“It has only been recently that the role of moderate volcanic eruptions on the global stratosphere has been recognized and evaluated,” Khaykin said. “Now we have a newcomer, which is wildfires. What is going to happen if we have stronger wildfires and a strong volcanic eruption at the same time? It’s quite scary because we realize we know quite little.”