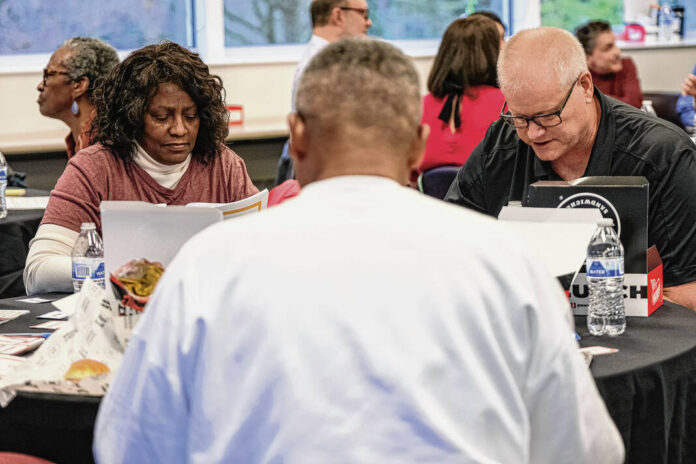

At the close of the United Way of Bartholomew County’s Racial Wealth Gap Simulation, organizers asked participants for a one-word reaction to the Black History Month interactive experience.

The responses came swiftly from around the conference room at the Doug Otto Center in Columbus.

Angry. Embarrassed. Disgusted. Hopeless.

Mark Stewart, United Way president, took that as a good sign that Thursday’s 90-minute exercise with a mix of people from community circles including human rights, law enforcement, local foundations, ministries and more had an undeniably shocking effect on the 24 people who took part.

And part of that shocking effect was that participants said they never fully realized that a host of federal laws dating back as far as President Andrew Johnson’s land policies and sharecropping from 1865 to 1880 have put America’s Black residents at a distinct financial disadvantage compared to whites.

For example, an 1865 federal law rescinded the government’s promise of 40 acres of land for former slaves. The federal laws and other material highlighted during the simulation were provided via Bread for the World, a Christian advocacy agency aiming to eradicate world hunger.

Participants discussed historic prejudicial federal policies as they moved through the simulation, which showed them the ways these policies has financial consequences for black people. For example, every participant moved through the simulation as a black or white person and was told to take a land, money, or missed opportunity card depending on the affects the policy had on the race they were representing.

The exercise left Black participants with little wealth and ample frustration.

“The simulation is simplified without claiming to be the complete picture (of the racial wealth gap),” said Joy Basa-King, United Way’s director of engagement.

Participant Shirley Trapp, whose involvement in helping the less fortunate locally made her The Republic’s Woman of the Year years ago, was among those stunned by how some elements of government-endorsed racist history further harmed an already struggling group.

After the Civil War, 30,000 Blacks owned small plots of land, compared to 4 million Blacks who did not.

“I feel ashamed that a person of my education with two master’s degrees didn’t already know some of this today,” said Trapp, who is Black.

Lori Thompson, a longtime community leader who is Black, mentioned what she sometimes hears from naysayers when such disadvantages are presented to highlight the racial wealth gap.

“They say ‘Well, that was a long time ago — but those kind of things are not still happening today,’” Thompson said.

The simulation demonstrated that such an assertion is untrue and that abuses have continued in the modern age. National figures presented showed that from 1949 to 1970, a million people lost their land to abuses of the power of eminent domain, allowing government to seize private property.

About 70 percent of those families were Black. Several participants chimed in the reminder that, through the years, plenty of laws have existed that have been unfair to minorities.

“Remember that slavery once was legal,” said Chris Price, chairman of United Way’s agency investment committee.

Stewart pointed out one glaring disparity in Bartholomew County: Whites are three times as likely as Blacks to own a home.

Basa-King explained the basics of the simulation, which first was presented several years ago.

“It helps people to have a deeper understanding of racial inequality at the structural level, and see how racial inequality relates to wealth, poverty, and basic needs,” Basa-King said.

She added that the simulation is to educate people about elements of history and injustice that she said most citizens are unaware of.

“We’re all here to learn,” Price said, “and to deepen our overall understanding.”