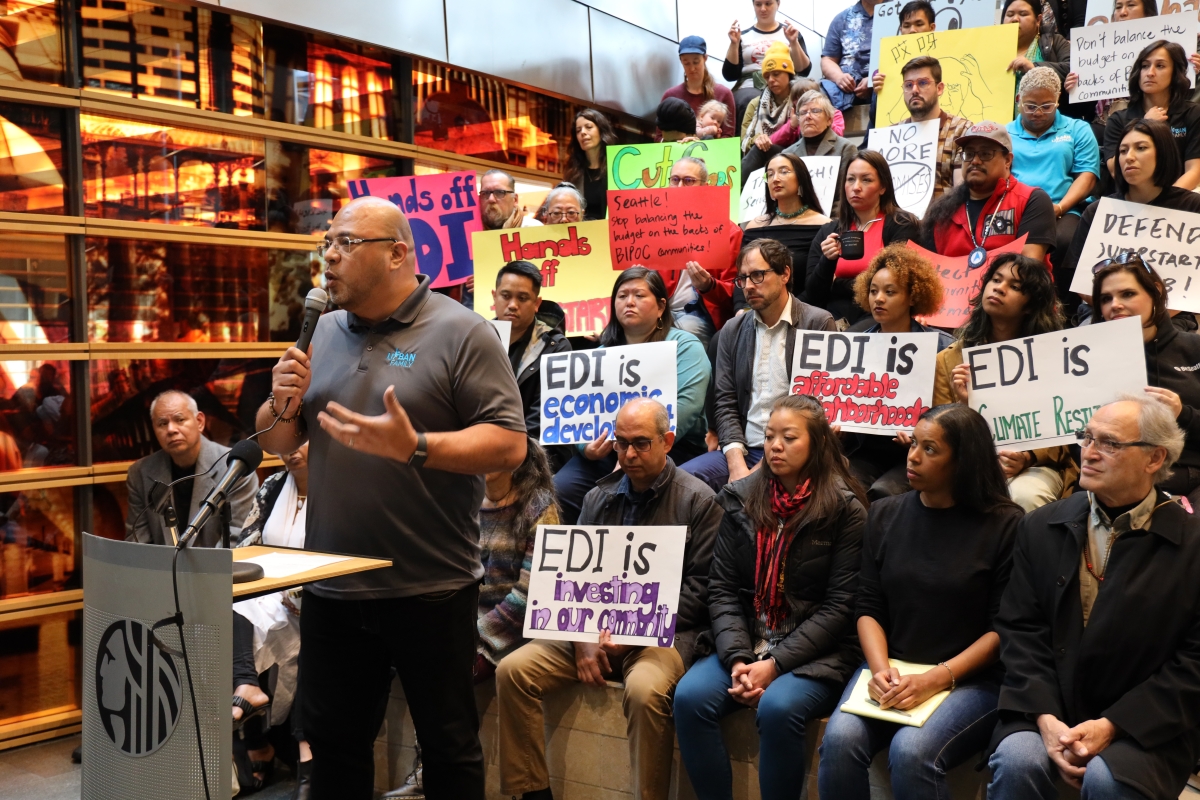

Hundreds of Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) community members and allies turned out at a May 28 Seattle City Council meeting to speak in defense of the Equitable Development Initiative (EDI) after its funding was threatened. As city leaders face the daunting prospect of filling a projected budget deficit of $250 million in 2025, the political controversy raised the specter that cutting city programs would have the deepest impact on communities of color.

Established in 2016, EDI is a first-in-the-nation city program intended to promote cultural, economic and housing developments in communities at the highest risk of displacement. The initiative provides funds and technical assistance to nonprofit organizations to become developers and construct their own buildings. Some of the projects that have been funded include affordable housing, community centers, child care facilities and art spaces.

Several projects supported by EDI made headlines over the last year during their openings, including the Ethiopian Village in Rainier Valley, which has 89 units of affordable housing for seniors, and the purchase of a house by y haw’Indigenous Creatives Collective to create an arts center.

EDI is one of the only dedicated municipal funding streams specifically intended for Seattle’s BIPOC communities. To date, 20 projects have been completed, with another 56 in the pipeline. More than $100 million has been allocated to projects, with funding coming from sales of city-owned land, Seattle’s tax on short-term vacation rentals like Airbnb and the JumpStart payroll expense tax on large corporations.

Late on Friday, May 24 — just ahead of the long Memorial Day weekend — news broke that Seattle City Councilmember Maritza Rivera had tendered an amendment to an ordinance that would impose a proviso on EDI funding, essentially freezing $25.3 million allocated to the program in the 2024 budget. The amendment was attached to a procedural bill that allowed Seattle to carryover unspent funds from 2023 into 2024. Rivera said her primary concern was about giving more money to EDI, when the program is already managing $53.5 million in funds that have been awarded to community groups and have yet to be spent.

The legislation shocked community members, who were caught off guard by the abrupt singling out of one of Seattle’s most important racial equity programs. A coalition of nonprofits, including many EDI beneficiaries, came together Memorial Day weekend, mobilizing more than 3,000 people to write letters to the city council in opposition to Rivera’s amendment. Another 175 people testified for three hours at the May 28 city council meeting.

Due to the overwhelming backlash, Rivera postponed her amendment for a week and then ultimately watered it down. The updated language simply asks the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD), which manages EDI, to produce a report due on September 24 on how to improve the program.

Ubax Gardheere, director of fund development for the Cultural Space Agency, said Rivera’s concerns were misplaced. Gardheere, who was the founding director of EDI and managed the program from 2016 to 2022, said it typically takes several years to acquire financing for most developers, regardless if they are non- or for-profit. Even after obtaining the funds, groups still need to past hurdles like land acquisition, permitting and design review before they can break ground. Because EDI does not disburse funds until a nonprofit has bought land or is ready to begin development, Gardheere said it looks like the $53.5 million is unused when in reality it has already been allocated.

Gardheere added that a big part of EDI is building capacity and supporting groups in acquiring the expertise needed to become developers and create something for their own communities.

“These are groups that have never had access or expertise on development,” Gardheere said. “They also have to build their capacity around that; they have to hire the right people.”

Despite the difficulties in community development, Gardheere said EDI was delivering many projects successfully. After working with EDI, some grantees have even been able to get federal funding. She said this lasting impact will allow more housing and community spaces to be built and owned by BIPOC organizations.

“I know of an organization that was funded initially by EDI for $1 million in 2022,” Gardheere said. “And within three years, they were able to raise $10 million.”

However, the pushback hasn’t appeared to change Rivera’s mind. At the May 28 city council meeting, she claimed community members were misinformed about her amendment and that it wouldn’t have impacted already-funded projects.

“I’ve moved to amend the agenda … in order to give time to correct disinformation that was irresponsibly given to [the] community about my proposed amendment,” Rivera said.

The $25.3 million Rivera had attempted to freeze is slated to go to a new request for proposals (RFP) to support capacity-building and help further anti-displacement efforts in BIPOC-led organizations — including many EDI grantees. This means, despite Rivera’s claims it wouldn’t, many of the projects in the pipeline would be directly affected by the lack of capacity-building funds.

Rivera is not the only politician threatening the future of EDI. According to Gardheere, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell has halted the rollout of the 2024 RFPs and also imposed a hiring freeze on most city departments, hampering the ability of OPCD to carry out its mandate. Harrell’s office has also requested OPCD identify cuts amounting to 40% of the department’s overall 2025 budget. A draft of this budget has not yet been made publicly available.

Chrissy Shimizu, executive director of Puget Sound Sage, said Rivera’s amendment has helped bring people together to fight for EDI and investments in communities of color. On June 4, the EDI coalition held a press conference at Seattle City Hall demanding the city not cut funding for communities of color and instead raise new revenue by taxing the rich.

At the press conference, Stephanie Ung, co-executive director of the nonprofit organization Khmer Community of Seattle King County, said that while the new version of Rivera’s amendment doesn’t place a freeze on EDI funds, it still imposes an onerous burden on OPCD staff. Ultimately, the modified amendment was passed by the council on June 4.

“We urge the council to invest their time and visit and interview each of us to understand the status of our projects and what value we bring to the city,” Ung said. “You will then all see the patterns of harm done that we are turning into healing.”

For Ayan Musse, an organizer with Whose Streets? Our Streets!, Rivera and the city council’s actions exhibited a condescending stance toward community members. Musse said the amendment was part of a racist double standard faced by BIPOC organizations, in which they are put under more scrutiny than white-led groups.

“There is no misinformation,” Musse said. “What has been written is right there. … All these [organizations] have been asking for meetings with them, and they didn’t bother to meet with them or go visit their projects.”

Paul Patu, the co-founder of the Southeast Seattle organization Urban Family, made it clear to Seattle politicians that if they threaten EDI, they could face electoral consequences.

“If you do not vote in favor of the people, the natural result is fire — a consuming fire,” Patu said.

Guy Oron is the staff reporter for Real Change. He handles coverage of our weekly news stories. Find them on Twitter, @GuyOron.

Read more of the June 12–18, 2024 issue.