Nearly 60 years ago, 16-year-old Rodney Hurst led a group of 33 Black teenagers in a peaceful sit-in to integrate a “whites only” lunch counter at a department store in Jacksonville, Florida.

At the same time a few blocks away, about 200 angry white men, many dressed as Confederate soldiers and armed with ax handles and bats, stormed the store to attack the demonstrators.

Many of the teenagers were beaten and bloodied. Some, like Hurst, escaped unharmed, but were forever psychologically scarred.

The episode became known as Ax Handle Saturday — Aug. 27, 1960, a date that takes on greater meaning now because, on its 60th anniversary next month, President Donald Trump will accept the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention in Jacksonville, mere miles from the attack.

This is the same Trump who has been divisive and inflammatory on racial issues, incapable or unwilling to at least attempt to bridge the divide during nationwide protests for justice after George Floyd was killed in police custody in Minneapolis on Memorial Day. Recently on Twitter, for example, Trump called the Black Lives Matter movement, which in many cases is leading the demonstrations, “a symbol of hate.”

And so, the juxtaposition of a vitriolic Trump speaking in Jacksonville on a day considered sacred in the city for Blacks — during the coronavirus pandemic, no less — creates a confluence of emotions for Hurst and African Americans, even if many are just learning about this dark moment in history.

“The best example I can give about this is when he was planning to speak in Tulsa on Juneteenth,” said Dr. Rudy Jamison, assistant director of urban education and community initiatives at the University of North Florida in Jacksonville, referring to a rally the president initially planned in Oklahoma for June 19, the day Blacks celebrate being freed from slavery. After a backlash, Trump moved his rally to June 20.

“Trump claimed he made Juneteenth ‘famous.’ I don’t know about that, but I know a lot of people have not heard about Ax Handle Saturday,” Jamison added. “And that speaks to a larger problem about what’s being taught. I call it educational malpractice, which is another form of violence.”

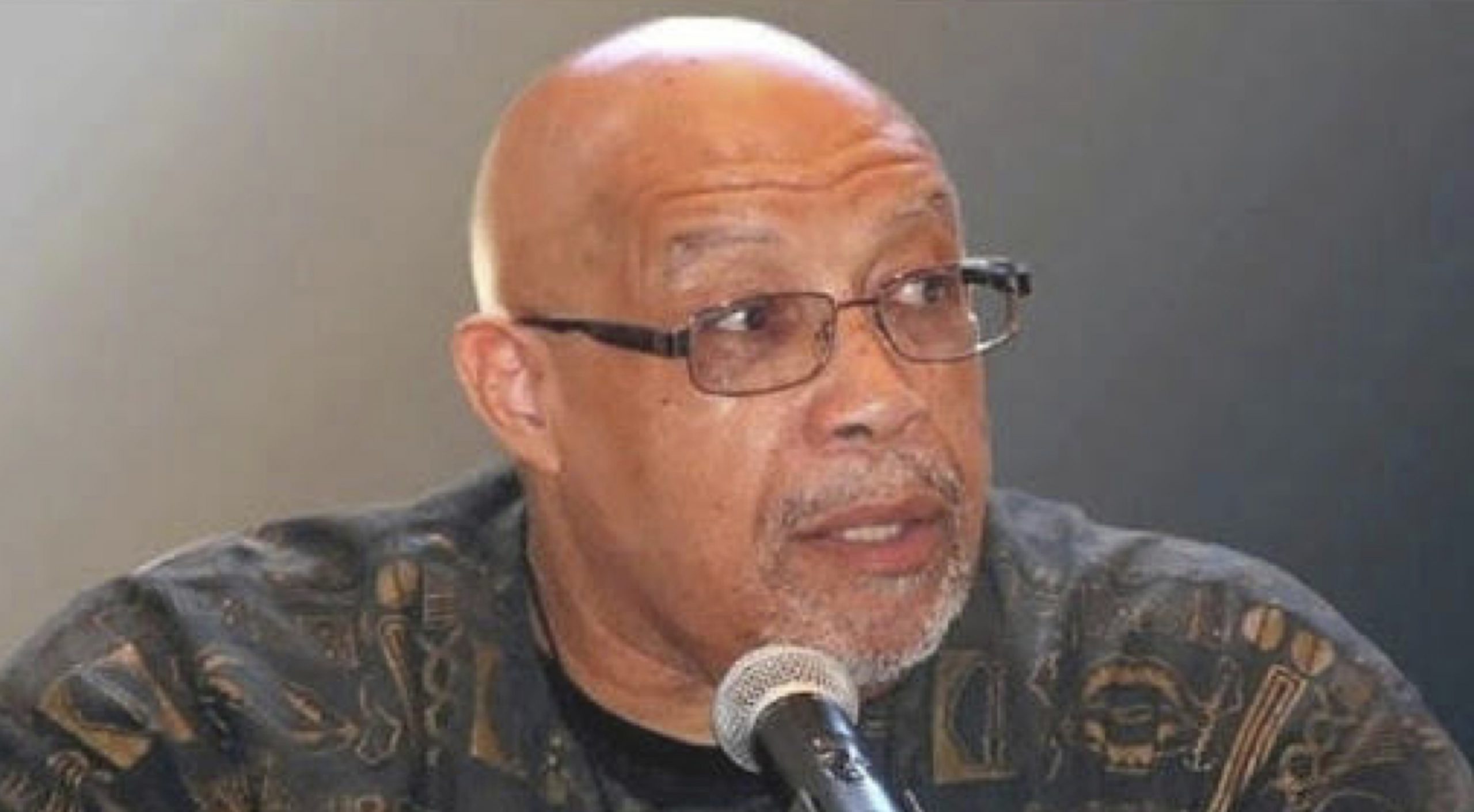

Hurst, 76, still lives in Jacksonville and has remained an activist in the community throughout his life, working as a historian and writing two books, one chronicling that frightening experience.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t think about that Saturday,” Hurst told NBC News. “It was real and surreal. We had heard something was going to happen, but we didn’t know what. But we protested anyway.”

And the demonstrations have not stopped for Hurst. He said he will be part of a competing event to the Republican National Convention, a commemoration of Ax Handle Saturday that is held every decade. But it will be counter to the convention in spirit and execution, he said.

“Our commemoration will be outside. We will wear masks and we encourage social distancing,” he said. “We will represent an interesting contrast on a day that white racist thugs attacked teenagers with bats and ax handles. We will highlight the cowardly way whites in the South dealt with our quest for Blacks’ seeking human dignity and respect.”

Anna Coleman, a Jacksonville resident and the owner of The V Spot Vegan Eatz and Treatz, said she only recently learned of Ax Handle Saturday and considers Trump’s presence in the city on its anniversary an affront, coincidence or not.

“The Black community has a never-ending fight for justice and equality, so to say that this is not the time is an understatement,” Coleman said of Trump and the RNC.

She said that, given a surge in coronavirus cases in Jacksonville and across Florida, the city’s mayor, Lenny Curry, a Republican, and Trump are obviously “not one bit concerned for the health and safety of any citizen in Jacksonville.”

“It’s all outrageous,” Coleman added.

Sixty years later, Hurst still finds it outrageous that a peaceful protest turned violent. Blacks were allowed to shop in W.T. Grant’s department store, but had to eat at a Black-only counter in the back.

”We could spend our money there, but not eat where we wanted,” Hurst said. “We had had enough. And we did not let the attackers deter us. We knew they were coming and we voted to sit in anyway. And after an agreed ‘cooling off’ period (of three weeks), we continued to protest and sit in.”

Hurst led his group for the next seven months. There were countless more sit-ins and a boycott throughout the city. Eventually, lunch counters in Jacksonville were integrated in the spring of 1961. Afterward, Hurst and a friend ate lunch every day for a week at previously “whites only” counters so they would “get used to” seeing Black people dine there, he said.

Ericka Durant, a Jacksonville native, said she is finding it hard to digest that Ax Handle Saturday’s anniversary will be tarnished by Trump’s presence in the city.

“Sick to my stomach,” Durant, a health care business analyst, said. “Trump accepting the nomination on the anniversary date of a literal race riot in Jacksonville is not only disgusting, but given the current tension surrounding race relations in this country, it is frightening.”

“There’s fear for what may happen if and when protestors show up while the president is in town,” she said. “Fear for a rage that is already at its boiling point. Fear because there is a virus that is still very active in the city, and the cases are growing daily. Fear because people are putting their lives at risk to fight for justice, and are being mocked by those that don’t understand.”

Durant said that while the mayor and others weighed the economic impact the convention could have on the city, she was weighing the mental health impact on Black Jacksonville natives, “especially the ones that were alive when this happened.”

“How much more can we take?” she said. “Is this going to be the breaking point for race relations and racism in 2020? I pray it isn’t, but right now I feel like that is all I can do.”

White-owned local newspapers like The Florida Times-Union and TV outlets did not initially report about the sit-ins or the attacks. “They wanted to black it out,” Jamison said. “And when they did cover it, they called the attack ‘a skirmish downtown’ and that ‘33 Blacks and nine whites had been arrested.’”

The black media in the area documented the event in greater detail and provided the few photos that captured what happened.

Hurst said he learned decades later that the Jacksonville police were aware that the teenagers would be assaulted and that many of the attackers were Ku Klux Klan members, but did nothing. “There was no police presence,” he said. “They let it happen.”

Hurst wrote the only comprehensive account of Ax Handle Saturday with the 2008 release of his award-winning book, ‘It Was Never About a Hot Dog and a Coke!’

In it, Hurst writes: “The Jacksonville Youth Council NAACP represented nonviolent, church-going, committed and dignified young people determined to be part of the solution and not part of the problem.”

Of Trump, Hurst said: “He’s part and parcel to the problem. I really don’t care if he comes or not to Jacksonville. Trump will be inextricably linked now to Ax Handle Saturday. He’s a racist president who deals with public events inside during a pandemic. … Not a good legacy.”