Paintings inspire lessons of an overlooked history, conversations on racism and justice

A new art exhibition at Montclair State University, Black Wall Street: A Case for Reparations, is sparking challenging conversations around issues of social justice and contributing to the growing work around the century-ago Tulsa Race Massacre, a footnote in U.S. history despite being among the country’s worst instances of racial violence.

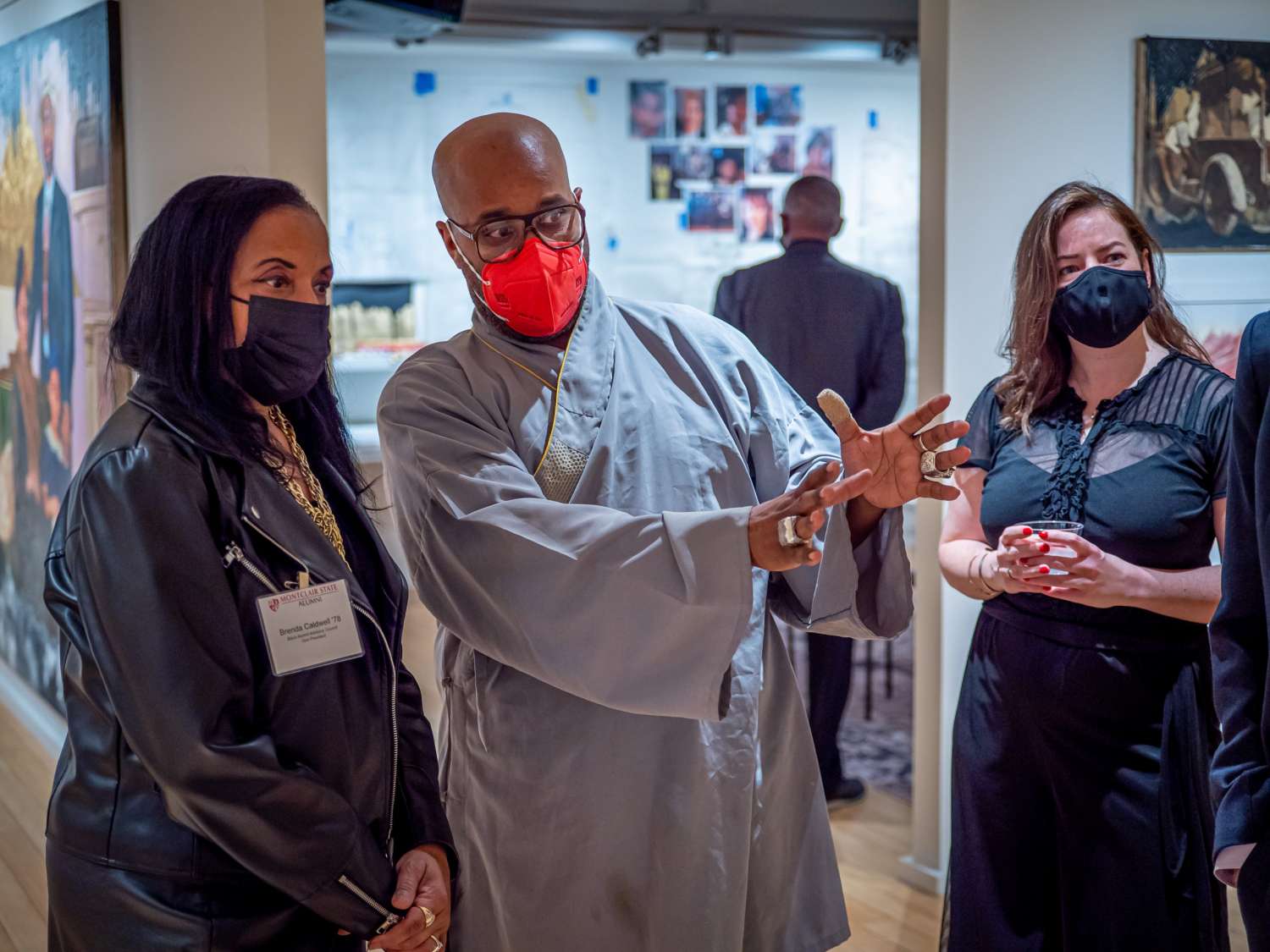

In a panel discussion on February 22, the artist, painter and filmmaker Ajamu Kojo, described the motivation behind the series of large-scale paintings installed in the George Segal Gallery, with University academics providing the context to the historic events of 1921, its depiction in the arts and call for long overdue reparations for the descendants of victims.

“Historically, this event was suppressed and not found in American history textbooks for over 60 years,” said College of Humanities and Social Sciences Associate Dean Leslie Wilson. “Against this backdrop, the beautiful and dignified artwork of Ajamu Kojo captures the wealth, dignity and community of the people of Tulsa’s Greenwood district.”

The series was inspired by the life and testimony of Olivia Hooker, a Greenwood survivor, who Kojo was able to interview before she died in 2018 at the age of 103. “She gave me her blessing to use her likeness for the centerpiece of this exhibition,” Kojo said.

Each portrait is framed by a black tar-like drip in the outer edges of the panel, a nod to Oklahoma’s crude oil that was a source of Greenwood’s thriving culture and wealth in spite of strong segregation laws.

Others have interpreted the dripping edges as foreboding the ominous events to come, Kojo said.

In 1921, a white mob burned down Greenwood, riled by rumors that a black teenager had assaulted a white woman. “An entire community was destroyed, with hundreds injured, more killed and at least 4,000 arrested by the Oklahoma National Guard,” Wilson said. “No whites were arrested as it was believed that the African Americans were the aggressors. Many of the African American dead were buried in mass unmarked graves. Reparations were paid to a white store owner whose guns were stolen. No compensation from the state or insurance companies was extended to the African American community.”

Despite years of lobbying, it was only in recent years that Oklahoma agreed to some investment in Greenwood and presented medals to the then 188 survivors.

“For me, it was not enough that people got a brass medal,” said Kojo who turned to his canvases to honor the survivors and descendants with the series of paintings that capture the “black excellence” and the prosperity of Greenwood residents. The artist called on professionals from his Brooklyn neighborhood – artists, lawyers, entrepreneurs – to pose and represent the characters in the pieces, designing the sets and wardrobes for portraits that pay homage to a reimagined past.

In response to a question about the meaning of being Black in America today, Wilson said, “The role of Black people is to take their pain and transfer their pain into signs of love and hope and aspiration. It’s a burden, but Black Americans have carried that burden for 400 years. Everyone is doing it in their own personal ways. What we’re looking at now is a moment of positive, hopeful change and a period of transition.”

While the exhibition neither ignores or denies the trauma experienced by Black Americans, Kojo said he purposefully focused his portraits on the thriving commerce and family life in Greenwood.

“When you walk through that exhibit you come out empowered,” said Psychology Professor Saundra Collins, “to elevate and keep reminding Black people to rise up.”

The exhibition is on view until April 23. The Segal Gallery is open Tuesday – Saturday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. For additional information, visit the University Galleries website at montclair.edu/galleries

Photo Gallery

Story by Staff Writer Marilyn Joyce Lehren. Photos by University Photographer Mike Peters. Videographer Christo Apostolou.